Not all disasters arrive like an earthquake. Some creep in like fog—silent, invisible, persistent. And by the time we realize the ground beneath us has shifted, the damage is done. A groundbreaking new study, published in the journal One Earth, has revealed that this may also be the story of our planet’s ecosystems. They may not collapse in fire and fury, but rather sag and splinter slowly, quietly rearranging themselves until one day, the world they held together is no longer recognizable.

Led by Professor John Dearing at the University of Southampton, alongside researchers from Rothamsted Research, Bangor University, and Edinburgh University, the study challenges the traditional narrative of tipping points—those sudden, catastrophic collapses in climate and ecosystem systems that have become icons of environmental warnings. Instead, it offers a sobering alternative: collapse may already be happening, hidden in plain sight.

The Myth of the Sudden Snap

For decades, scientists and policymakers have focused on tipping points as sharp breaks—like a lake abruptly turning green with algae, or the sudden disintegration of an ice shelf. These models have painted collapse as an obvious event, something impossible to miss and therefore possible to plan around. But what if nature doesn’t always break like that?

“Some systems snap. Others sag,” explains Professor Simon Willcock of Rothamsted Research, one of the study’s co-authors. “That sagging, that slow reconfiguration of complexity under pressure, might be even more dangerous—because we might not see it until it’s too late.”

In other words, the most dangerous transitions may not come with alarms and smoke. They may unfold silently, over years or decades, their warning signs muffled by the sheer scale and complexity of the systems involved. It’s not the scream we should fear, but the whisper.

Physics, Magnets, and Forests

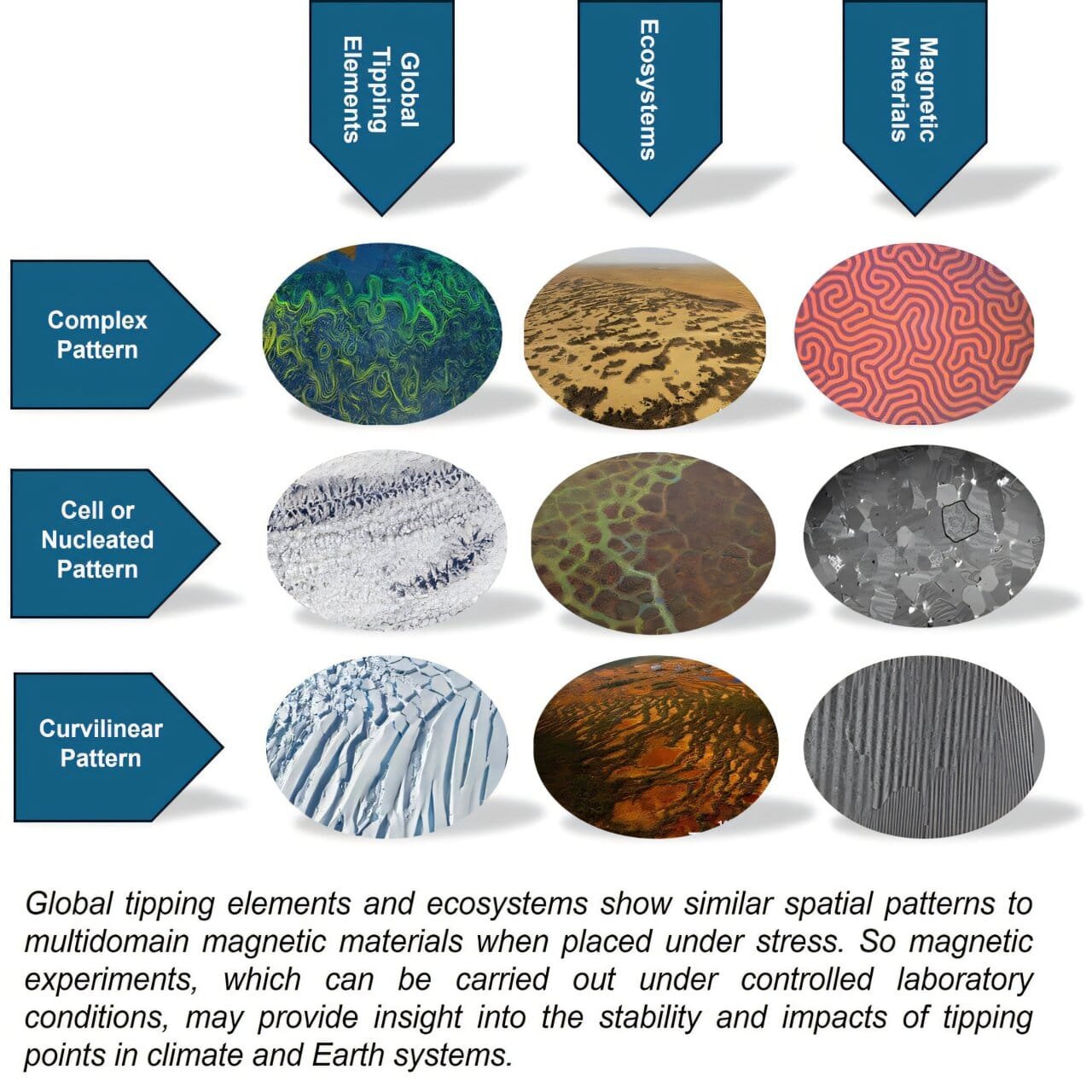

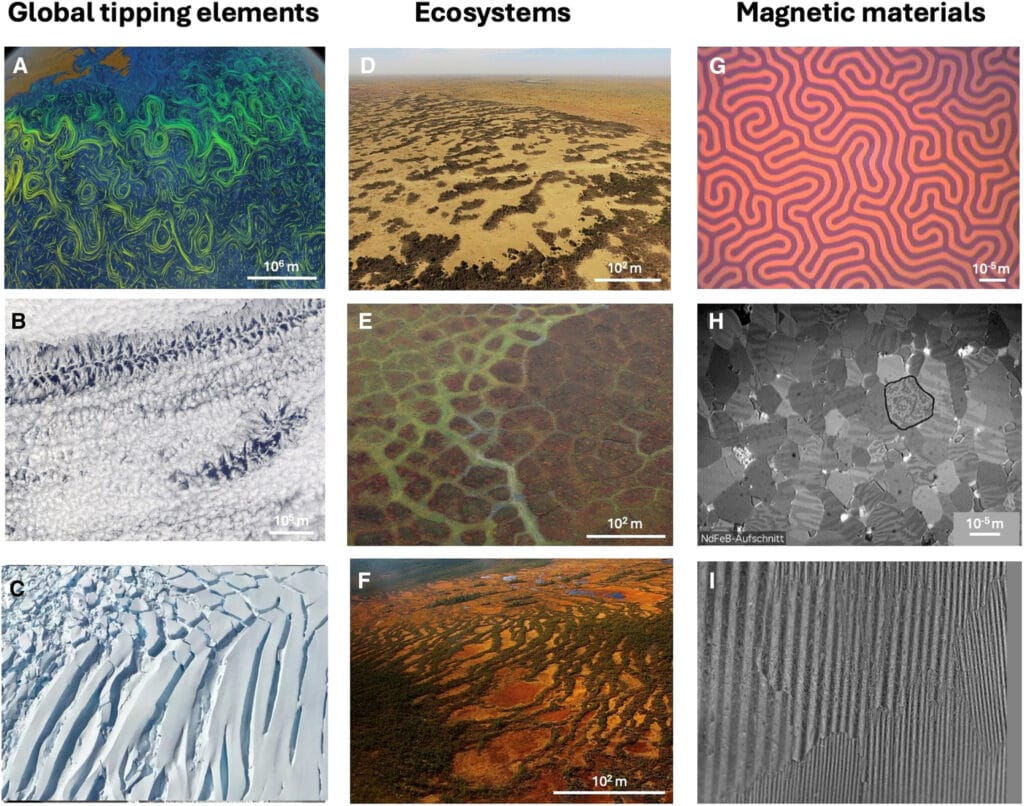

To explore this unsettling idea, the research team looked not to nature directly, but to physics—specifically, the behavior of magnetic materials. In the laboratory, scientists can induce shifts in magnetic systems by applying external forces. The responses can be abrupt or gradual, depending on the material’s internal complexity.

This simple-seeming insight has profound implications. Homogeneous magnetic materials—those with little internal variation—tend to exhibit sudden, irreversible transitions under stress. But more complex materials reorganize slowly, piece by piece, realigning as the strain increases. These incremental changes can mask the onset of collapse until the system is deeply, perhaps irreversibly, altered.

This analogy sheds light on how massive, complex ecological systems—rainforests, coral reefs, ice sheets, ocean currents—might behave under climate stress. Unlike simpler systems, their collapses may not arrive as single dramatic events. They may unfold like the slow bend of a bowstring, holding tension, until the arc becomes too steep to bear.

The Danger of Stability’s Illusion

A rainforest looks unchanged for decades. The same trees, the same birdsong, the same canopy. But under that familiar face, something is happening. Species shift. Soil chemistry changes. Hydrological cycles weaken. The forest is still standing—but it’s not the same forest. The resilience is thinning.

These slow shifts don’t look like collapse. They look like change. But eventually, they reach a threshold. The system, stretched and stressed, can no longer hold its shape. And when the tipping finally comes, there may be no going back.

That’s the danger. Gradual collapses don’t trigger political panic. They don’t make headlines. They don’t rally emergency action. Yet by the time they become obvious, it may be too late to reverse them.

As Professor Roy Thompson of the University of Edinburgh, another co-author, put it: “Slow changes can be deceptive.” And in systems as large as the Amazon, the Greenland Ice Sheet, or the Atlantic Ocean Conveyor, what appears slow to us can still be devastatingly fast for life that depends on stability.

Time, Scale, and the Blind Spots of Policy

One of the most urgent warnings from the study is about how we perceive scale. Policymakers and scientists often look at environmental systems from a distance, using global models and regional averages. But complexity exists at every level—species, genes, microclimates, niches—and change often begins in the smallest details.

From afar, a forest may seem intact. But look closer, and the signs of strain appear. Fewer pollinators. Shifts in plant chemistry. Microbial changes in the soil. If we miss these early signals—if we fail to see how ecosystems are reorganizing at the smallest levels—we risk being blindsided when the final break comes.

This isn’t just a scientific insight. It’s a political one. If we don’t refine how we monitor ecosystems—if we keep looking at blurry, coarse data—we may never see the collapse coming. And worse, we may tell ourselves that things are fine, that there’s still time, while the systems we depend on are quietly failing beneath our feet.

Whispers in the Warming

The study also highlights the role of climate acceleration in this process. The faster the stress—the quicker the warming, the more rapid the deforestation, the sharper the pollution—the more likely even complex systems are to shift suddenly. Gradual collapse becomes abrupt. What once might have unfolded over centuries now happens in decades—or less.

This is why slowing the pace of climate change is more than just a goal. It’s a necessity. As Professor Dearing puts it, “Slowing the rate of climate change is essential—not only to avoid catastrophic collapse, but to buy time for systems to adapt and recover.”

Time is the currency of resilience. The more time ecosystems have to adjust, the better the chances they can reorganize in ways that preserve life. Without that time, even the most complex, adaptive systems may fail. Not with a bang—but with a slow, silent fall.

The Imperative to Act Before the Crash

There is, perhaps, a strange hope in these findings. If some systems collapse gradually, then maybe they can be restored gradually—if we act in time. Early intervention, targeted restoration, reduction of stressors—these may still work, even in systems already bending under pressure.

But that window is narrow. The key is awareness. We must learn to recognize the whispers of collapse. The early signs. The slow sagging of once-stable systems. And we must act before the bow breaks.

“This work flips the script on climate risk,” said Willcock. “Not all tipping points are abrupt. Some are slow and silent—and we may already be inside them. If we wait for ecosystems to scream, we’ll have waited too long. The real danger is in systems that whisper while they fall apart.”

Redefining Collapse for a Changing Planet

The implications of this research ripple far beyond the academic world. They demand a reevaluation of how we define environmental risk, how we build models, and how we prioritize action. The idea that not all tipping points are sudden shifts the focus from dramatic collapse to subtle change. It asks us to be more attentive, more precise, and more proactive.

We need better monitoring—higher-resolution data, more sensitive tools, and more localized insights. We need policies that reflect the messy, nonlinear nature of ecological change. And above all, we need humility: the understanding that our models, our categories, and even our instincts may not capture the full complexity of Earth’s living systems.

The Moral of the Magnet

There is something poetically fitting about magnets—silent, invisible forces shifting unseen parts—as a metaphor for ecological collapse. The systems that support life on Earth are full of similar unseen forces. They balance nutrient flows, carbon cycles, species interactions, and hydrological rhythms with a delicate, often invisible coordination.

When they are pushed, they don’t always scream. Sometimes, they simply shift. Sometimes, they reorganize. And sometimes, they die quietly, leaving us only the ghost of what was once there.

Understanding this doesn’t just change our science. It changes our responsibility. Because now, we know the warning signs may not come in loud alarms. They may come in quiet changes. And it’s up to us to listen.

Reference: Reconciling global tipping point theories: insight from magnetic experiments, One Earth (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101358. www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltex … 2590-3322(25)00184-8