When we gaze at the night sky, scattered with countless stars, it is easy to imagine that life must be everywhere. Yet so far, Earth remains the only known planet where life has taken hold. It is our fragile oasis, a blue world wrapped in a stable atmosphere and filled with liquid water. But this life-friendly environment was not always our reality. Billions of years ago, Earth was anything but welcoming. In fact, the conditions on the young planet were hostile to the very chemistry required for life to emerge.

Recent research has shed new light on this mystery, suggesting that Earth’s transformation into a habitable planet was not a gradual unfolding of inevitability, but rather the result of a cosmic accident—a colossal collision that changed everything.

The Harsh Birth of the Inner Planets

To understand why Earth’s early days were so unpromising, we must journey back to the beginning of the solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. The Sun had just ignited, and around it swirled a vast cloud of gas and dust. Within this swirling disk, matter began to clump together, eventually giving rise to the planets.

But not all planets formed under the same conditions. The region closest to the Sun—where Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars reside today—was a place of blistering heat. Here, volatile elements essential for life, such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, could not condense. Instead, they remained in gaseous form, swept away by the young Sun’s intense radiation.

This meant that the proto-Earth, the rocky embryo that would one day become our planet, was born nearly dry and barren. Unlike the icy bodies forming in the cooler outer reaches of the solar system, which could trap water and carbon-rich compounds, Earth began as a hostile, desolate rock.

Tracing Earth’s Chemical Story

How do we know this? A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the University of Bern provides one of the clearest answers yet. Using advanced techniques in isotope geochemistry, scientists reconstructed the chemical fingerprint of the young Earth.

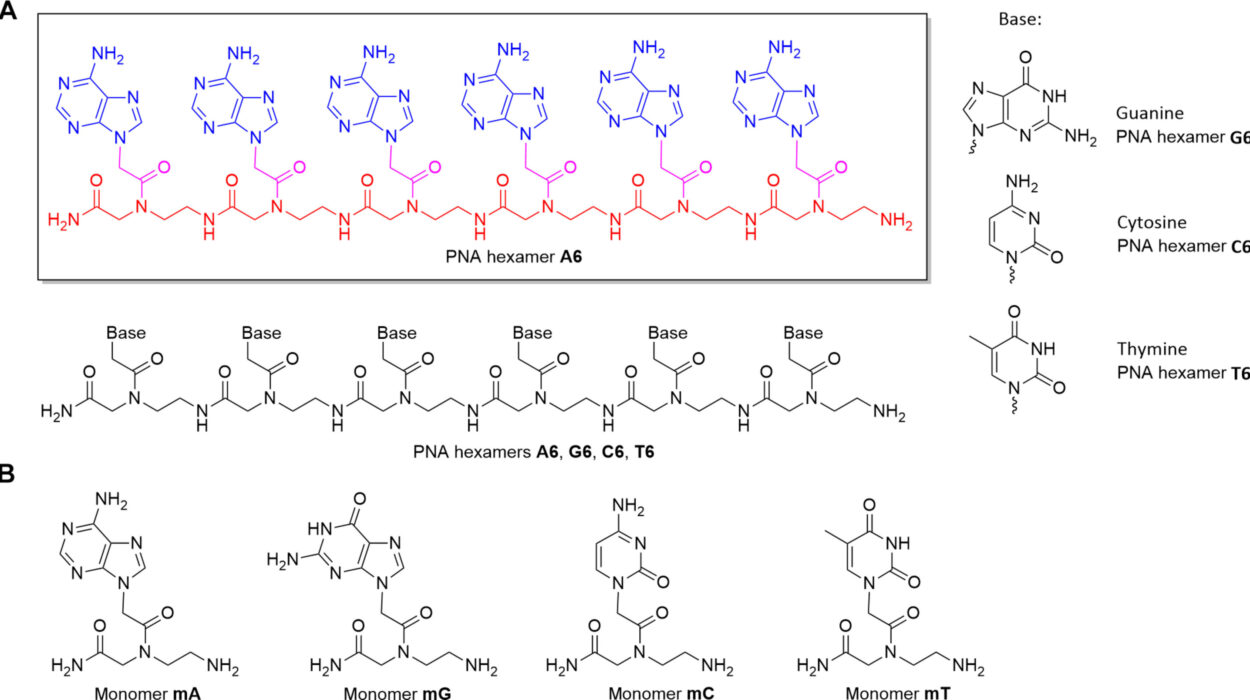

The key lay in analyzing isotopes—atoms of the same element with different weights—locked inside ancient meteorites and terrestrial rocks. In particular, the team used a radioactive isotope, manganese-53, which decays into chromium-53 with a half-life of about 3.8 million years. This isotope served as a kind of cosmic stopwatch, allowing scientists to pinpoint when the proto-Earth’s chemical composition was established.

The results were astonishing. They revealed that Earth’s chemical identity was essentially complete within just three million years of the solar system’s birth. In cosmic terms, this was almost instantaneous. But the chemical mixture that resulted was far from life-friendly. Earth, in its infancy, was a dry, rocky planet with almost none of the volatile substances that life requires.

The Collision That Changed Everything

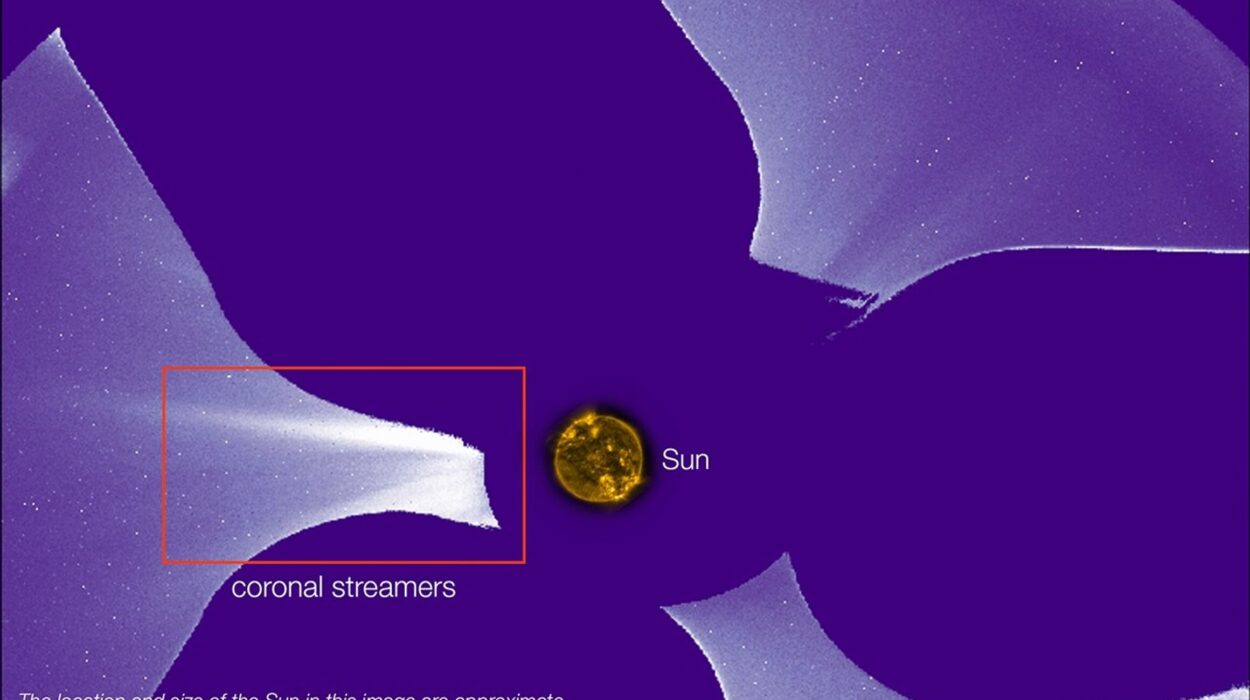

If Earth began as a barren rock, how did it become the lush, water-filled world we know today? The answer, researchers argue, may lie in one of the most dramatic events in planetary history: the collision with a body now known as Theia.

Theia was a Mars-sized planetesimal that formed farther from the Sun, in a cooler region of the solar system where water and other volatile elements could accumulate. At some point, perhaps around 50 million years after the solar system’s birth, Theia slammed into the proto-Earth in a cataclysmic impact.

This collision was unimaginably violent. It released enough energy to melt large portions of both bodies, scattering debris into orbit that would eventually coalesce into the Moon. But it may also have delivered the missing ingredients for life. If Theia carried water and carbon-rich materials, as many scientists believe, the impact could have seeded Earth with the essential building blocks of habitability.

Without that chance collision, Earth might have remained forever dry, barren, and lifeless.

The Role of Chance in Life’s Existence

The implications of this research are profound. It suggests that Earth’s life-friendliness was not the product of a smooth, inevitable progression, but rather the outcome of a cosmic coincidence. Had Theia formed elsewhere, or had it missed Earth entirely, our planet might never have gained its oceans, its atmosphere, or its potential for biology.

As Professor Klaus Mezger of the University of Bern puts it, “Life-friendliness in the universe is anything but a matter of course.” Earth’s story may be less about destiny and more about chance—a reminder of how fragile and unlikely our existence truly is.

This perspective forces us to reconsider the broader search for life beyond Earth. If habitability depends not only on being in the “right place” near a star but also on rare cosmic accidents like Earth’s collision with Theia, then life may be even scarcer than we imagine.

Looking Deeper into the Past

The Bern team’s study is only the beginning. Scientists now hope to model the proto-Earth–Theia collision in more detail, exploring not just its physical aftermath but also its chemical consequences. How exactly did Theia deliver volatile elements to Earth? How did the violent mixing of materials shape both the Earth and the Moon? And could similar processes have occurred on other planets or moons in our galaxy?

These questions remain open, but what is clear is that Earth’s story is not one of inevitability. It is a story of violent beginnings, rare events, and precarious chances.

The Fragility of Our Cosmic Home

When we look at Earth today—with its oceans teeming with life, its skies alive with birds, its forests brimming with green—we are witnessing the end result of billions of years of cosmic history, shaped in part by a single collision long ago. That impact may have determined whether we exist at all.

In this sense, Earth is not just a planet—it is a fragile miracle. Its story is not only scientific but deeply emotional. It reminds us of our place in the cosmos: small, improbable, and yet profoundly significant. We are the children of stardust and chance, alive because the universe, at least once, allowed the right conditions to align.

As we continue to search the skies for other habitable worlds, we must remember that life is not guaranteed. It is a rare gift, born of cosmic accidents and fragile balances. And on our tiny blue planet, against all odds, that gift has flourished.

More information: Pascal M. Kruttasch et al, Time of proto-Earth reservoir formation and volatile element depletion from 53 Mn- 53 Cr chronometry, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw1280