Sleep is often described as life’s most natural medicine—a mysterious yet essential state that restores, heals, and renews. While we spend nearly a third of our lives asleep, few of us truly appreciate the depth of its influence on health and aging. For older adults, sleep is not just a nightly ritual but a critical cornerstone of physical vitality, mental sharpness, and emotional resilience. Yet as we age, sleep tends to change—becoming lighter, shorter, and more fragmented.

This decline is not a simple inconvenience. Poor sleep in later life has been linked to weakened immunity, memory loss, mood disorders, and even higher risks of chronic diseases like heart disease and dementia. Understanding why older adults need better rest, and how to achieve it, is not just about comfort—it is about quality of life, longevity, and dignity in aging.

How Sleep Works: The Body’s Nightly Symphony

Sleep is not a uniform state but a complex, cyclical process that moves through different stages, each with its own purpose. Broadly, it is divided into non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

During NREM sleep, especially its deepest stage (slow-wave sleep), the body performs much of its repair work—releasing growth hormones, rebuilding tissues, and consolidating certain types of memory. REM sleep, characterized by vivid dreams, is equally vital for emotional regulation, creativity, and learning.

These cycles repeat about four to six times per night in a healthy adult, forming the architecture of restorative sleep. But with age, this architecture begins to shift. Older adults often spend less time in slow-wave and REM sleep, waking up more frequently throughout the night. This lighter sleep may leave them feeling unrefreshed even after a full night in bed.

Why Sleep Changes With Age

Aging affects nearly every biological system, and sleep is no exception. Several factors contribute to altered sleep patterns in older adults:

Changes in Circadian Rhythms

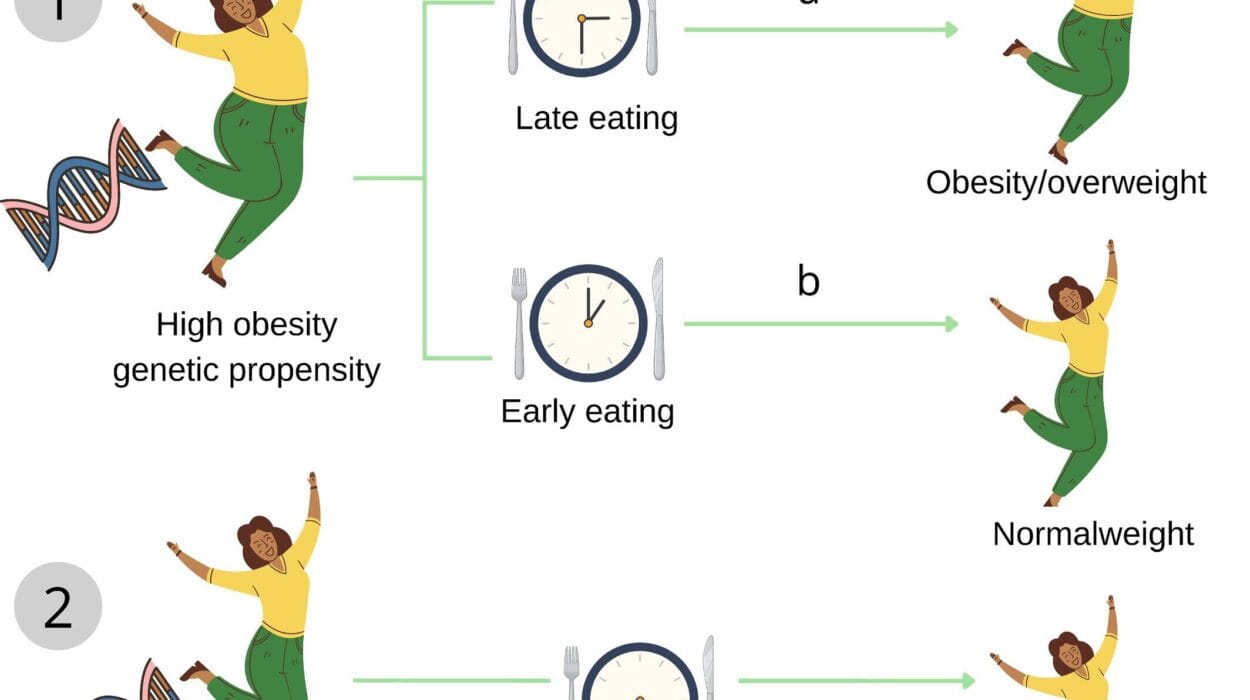

Our internal biological clock, or circadian rhythm, regulates the timing of sleep and wakefulness. With age, this rhythm tends to advance, meaning older adults often feel sleepy earlier in the evening and wake earlier in the morning. While not inherently harmful, this shift can conflict with social schedules and reduce sleep duration.

Decreased Melatonin Production

Melatonin, the hormone that signals the body to prepare for sleep, declines with age. Lower levels of melatonin can make it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep, especially in environments with artificial light exposure.

Medical Conditions

Chronic conditions common in older age—such as arthritis, heart disease, diabetes, or gastroesophageal reflux—can cause discomfort that interrupts sleep. Neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, are particularly disruptive, often causing fragmented sleep-wake cycles.

Medications

Older adults are more likely to take medications that interfere with sleep, including drugs for blood pressure, asthma, depression, or pain. These may cause insomnia, restless legs, or vivid dreams that fragment rest.

Sleep Disorders

Conditions such as sleep apnea (periodic pauses in breathing during sleep) and restless legs syndrome become more common with age. Both disorders prevent deep, restorative sleep and increase risks of cardiovascular and cognitive decline.

The cumulative effect is that older adults not only sleep less but often sleep less efficiently, spending more time in lighter stages of sleep and less in the deep, restorative phases.

Why Sleep Matters More With Age

While sleep is important at every stage of life, its role in aging is particularly profound. As the body becomes more vulnerable to disease and cognitive decline, the restorative power of sleep takes on heightened importance.

Memory and Cognitive Health

Sleep is a powerful ally of the brain. During slow-wave sleep, the brain consolidates declarative memories—facts and experiences—while REM sleep strengthens emotional and procedural learning. Without sufficient quality sleep, older adults may struggle with recall, attention, and problem-solving.

Emerging research has shown that deep sleep may also play a critical role in clearing beta-amyloid, the toxic protein linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Poor sleep has been associated with higher amyloid buildup, suggesting that disrupted sleep may accelerate cognitive decline.

Physical Repair and Immunity

Deep sleep stimulates the release of growth hormone, which is crucial for repairing tissues, maintaining muscle mass, and supporting bone health. Adequate rest also enhances immune function. Older adults, already at increased risk of infections, benefit greatly from the immune-boosting power of sleep.

Emotional Stability

Sleep acts as a regulator of mood and stress. REM sleep, in particular, helps process emotional experiences, reducing the sting of negative memories. Chronic sleep disruption in older adults often correlates with depression, anxiety, and irritability, creating a cycle where mood problems further impair sleep.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health

Poor sleep has been linked to higher risks of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. For older adults, whose cardiovascular systems are already under strain, the protective effects of sleep are critical. Deep, restorative rest helps regulate blood pressure, blood sugar, and appetite-controlling hormones.

Longevity and Quality of Life

Sleep is not just about surviving longer but about living better. Research shows that older adults with good sleep quality report greater life satisfaction, better mobility, and stronger social engagement. In contrast, chronic insomnia or sleep apnea can erode independence, increasing the risk of falls, hospitalizations, and premature mortality.

The Emotional Experience of Aging and Sleep

The changes in sleep with age are not only biological—they are deeply emotional. For many older adults, the frustration of lying awake at night or waking too early brings anxiety and a sense of loss. Sleep, once effortless, becomes elusive.

Some may blame themselves, fearing that sleeplessness is a sign of decline. Others may feel isolated, as partners sleep soundly beside them. These emotional burdens can compound the physical effects, creating a feedback loop where worry about sleep makes it even harder to rest.

It is important to understand that sleep changes are not a personal failure but a natural part of aging. Recognizing this truth can help older adults approach sleep with patience, compassion, and proactive strategies rather than fear.

Strategies for Better Sleep in Older Adults

Improving sleep in later life requires both medical attention and lifestyle adjustments. While the specific approach will vary, some principles are widely supported by science.

Creating a Sleep-Conducive Environment

The bedroom should be cool, quiet, and dark. Comfortable bedding and supportive mattresses can reduce nighttime discomfort, particularly for those with arthritis or back pain. Limiting exposure to blue light from screens before bed helps preserve natural melatonin rhythms.

Supporting Circadian Rhythms

Exposure to natural daylight during the morning and afternoon can help reinforce healthy circadian rhythms. Evening routines that signal relaxation—such as reading, listening to soft music, or gentle stretching—prepare the body for rest.

Prioritizing Physical Activity

Regular exercise during the day promotes deeper sleep at night, though strenuous activity should be avoided too close to bedtime. Even light activities like walking, gardening, or tai chi have been shown to improve sleep quality in older adults.

Nutrition and Hydration

Avoiding heavy meals, caffeine, and alcohol in the evening can reduce nighttime awakenings. Hydration is important, but excessive fluid intake before bed can lead to disruptive bathroom trips.

Managing Medical Conditions

Effective management of chronic pain, cardiovascular disease, or respiratory problems often improves sleep. For sleep-specific disorders like sleep apnea, medical devices such as CPAP machines can dramatically improve rest and health outcomes.

Mind-Body Practices

Meditation, mindfulness, and relaxation techniques have been shown to reduce insomnia and improve sleep efficiency. These practices also enhance emotional well-being, making them particularly valuable for older adults navigating life transitions.

The Role of Healthcare in Sleep and Aging

Healthcare providers play a crucial role in identifying and addressing sleep issues in older adults. Too often, poor sleep is dismissed as an inevitable part of aging, leaving patients untreated. Physicians, geriatric specialists, and sleep medicine experts can help distinguish between normal changes and treatable sleep disorders.

Polysomnography (sleep studies) can diagnose conditions like sleep apnea, while cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) remains the gold standard for chronic sleep difficulties. Unlike sleeping pills, which can pose risks for falls, memory problems, and dependency in older adults, CBT-I addresses the underlying thought patterns and behaviors that perpetuate insomnia.

Looking Ahead: Research and Innovation

Sleep science is rapidly evolving, and its implications for aging are profound. Researchers are exploring how enhancing deep sleep could slow cognitive decline, how wearable technology can monitor sleep quality at home, and how tailored light therapy might reset disrupted circadian rhythms.

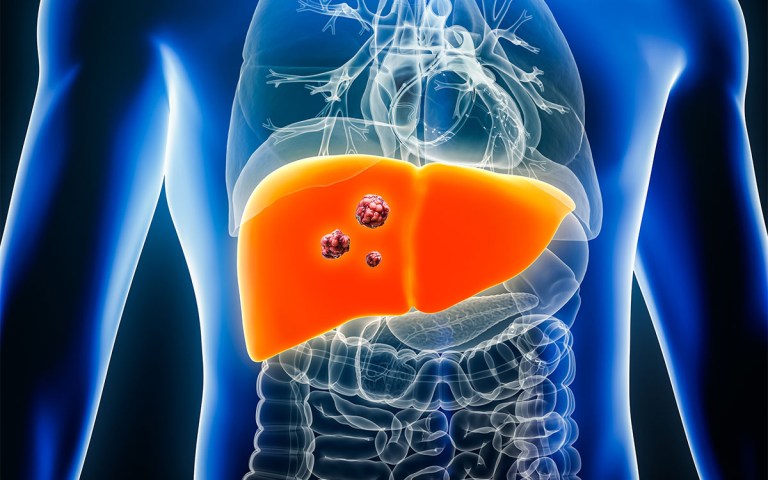

Some studies suggest that interventions to improve sleep could delay or even prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Others are investigating whether sleep enhancement might strengthen vaccines or reduce cancer risks in older adults.

The future may hold new therapies that restore youthful sleep patterns, but even now, simple changes in lifestyle, medical care, and awareness can make a remarkable difference.

Sleep as the Gateway to Healthy Aging

In the end, sleep is not a luxury but a biological necessity—a nightly gift that sustains life itself. For older adults, good sleep is the difference between merely surviving and truly thriving. It is the fuel for memory, the balm for the heart, the stabilizer of mood, and the healer of the body.

Aging brings inevitable changes, but poor sleep does not have to be accepted as destiny. With understanding, compassion, and the right strategies, older adults can reclaim rest and, in doing so, reclaim vitality.

Sleep is the quiet foundation upon which healthy aging is built. Protecting it means protecting independence, joy, and dignity in life’s later chapters. And that, perhaps, is the greatest gift rest can offer.