Sixty-five million years ago, a massive asteroid slammed into what is now Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, unleashing a chain of events that wiped out most of Earth’s species — including the dinosaurs. The event was so devastating that it reshaped life on Earth forever, and its story has become a permanent fixture in our collective imagination. Somewhere in the back of our minds, the question lingers: Could it happen again — and if so, will it happen while we’re alive?

Science has long had the answer: yes, it could happen again. But the more nuanced question is how likely it is to happen within a single human lifetime. A new study led by planetary scientist Carrie Nugent aims to answer exactly that — and the results might surprise you.

The Numbers Behind the Fear

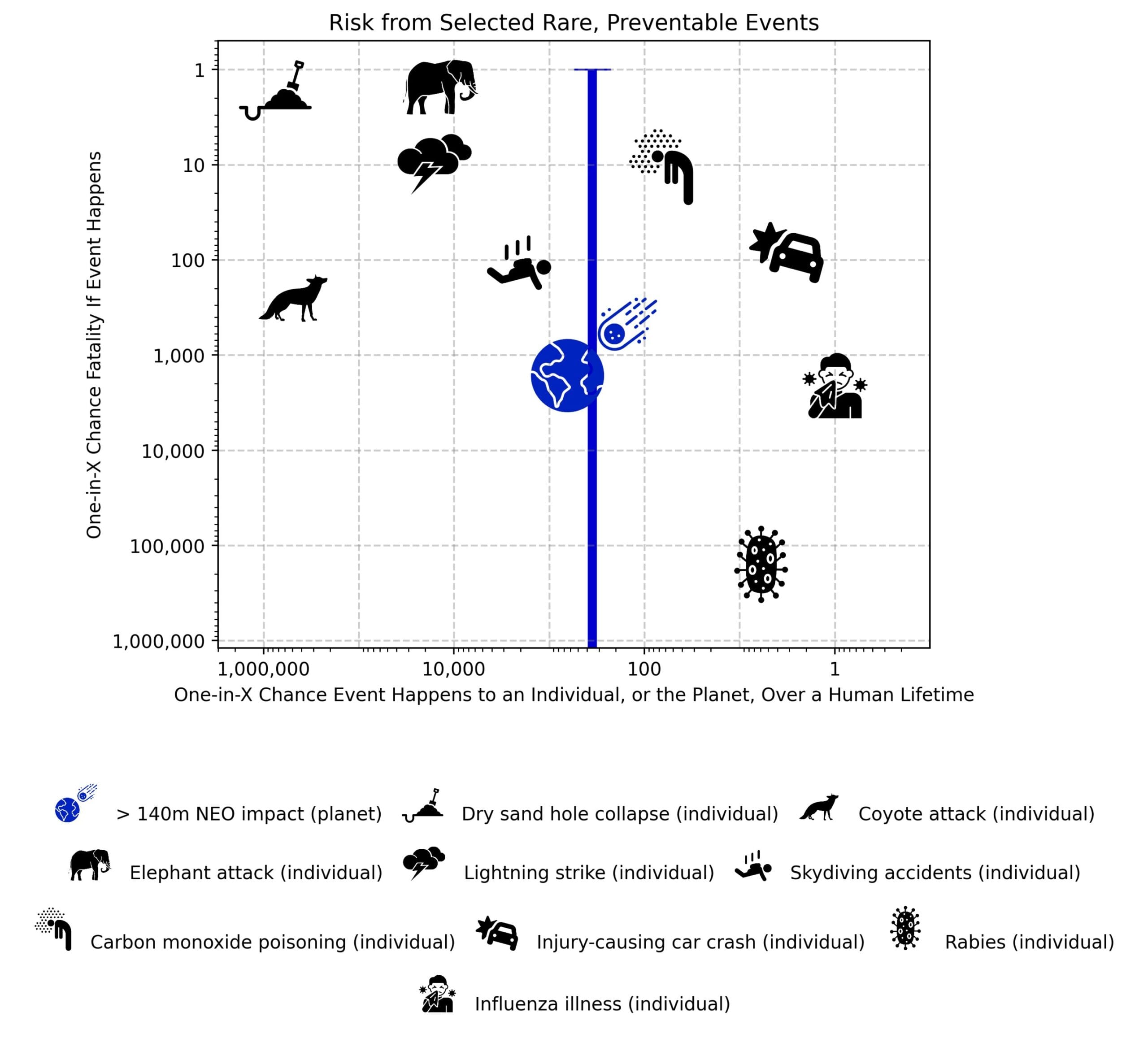

The research, now available on the preprint server arXiv and soon to be published in the Planetary Science Journal, tackles asteroid risk in a way that’s both scientifically rigorous and easy for the public to grasp. Previous estimates of asteroid danger exist, but they can feel abstract, buried in technical jargon and raw probabilities. Nugent and her colleagues wanted to bring those numbers down to Earth — by comparing asteroid impact risk with everyday hazards.

To do this, the team ran simulations involving 5 million near-Earth objects (NEOs), each more than 140 meters in diameter — big enough to cause regional devastation if they were to strike. Over a simulated 150-year period, they tracked how often these virtual asteroids collided with Earth, then calculated the odds of such an impact occurring during an average human lifetime of 71 years.

Their results: an asteroid of this size hits Earth roughly once every 11,000 years. That may sound like the universe giving us a reassuring wink — but in statistical terms, it’s not zero. And importantly, those odds are higher than some hazards people think of as more “real,” such as being struck by lightning or attacked by a coyote.

Not All Asteroids Are Created Equal

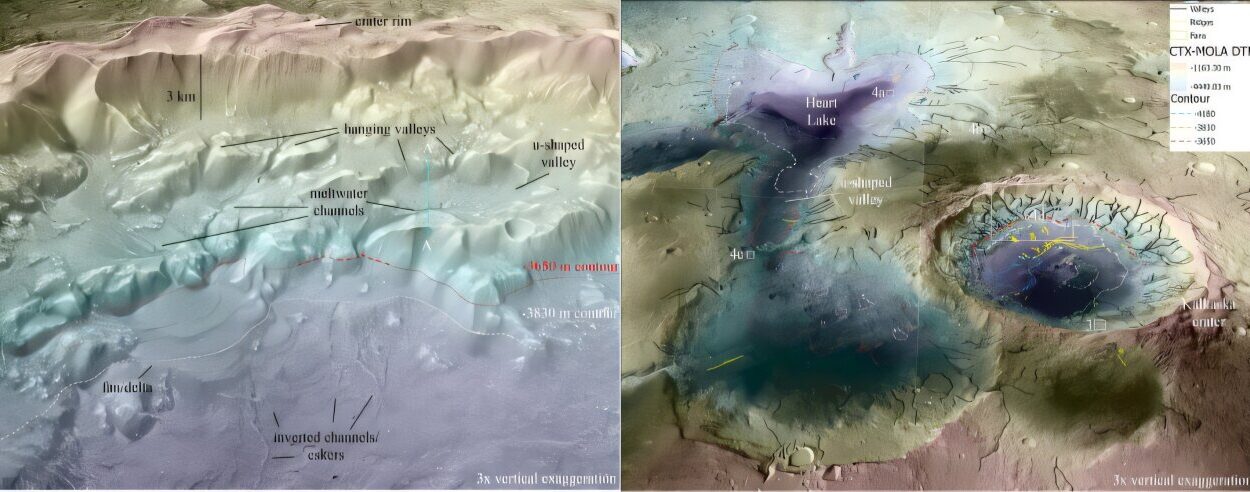

Asteroids come in all shapes and sizes, and their danger depends on more than just their diameter. The study highlights a crucial detail: a 140-meter asteroid hitting an uninhabited stretch of ocean might cause no fatalities at all. On the other hand, a slightly larger asteroid — say, in the 180–200 meter range — could affect over a million people if it hit a densely populated area.

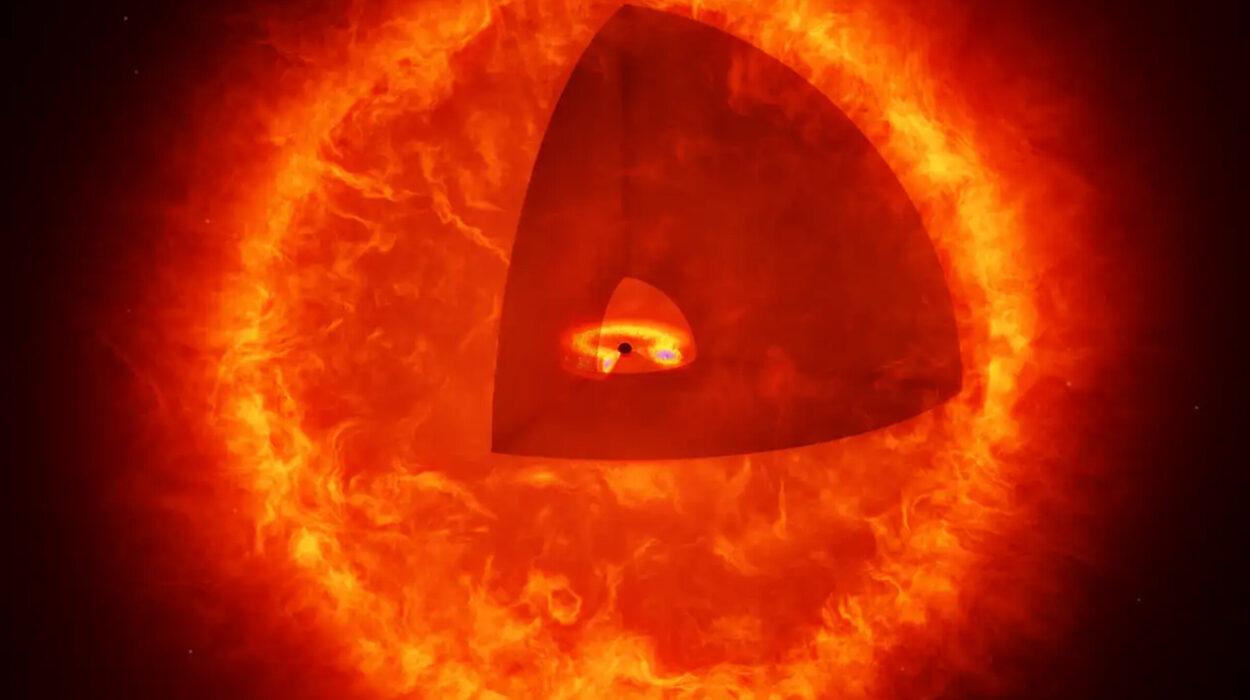

And then there are the giants. A 10-kilometer-wide asteroid like the one that ended the dinosaurs’ reign would have global consequences, altering the climate and threatening civilization itself. Thankfully, such civilization-ending impacts are even rarer, occurring on timescales of tens of millions of years.

Comparing Cosmic Threats to Earthly Dangers

One of the most eye-opening parts of the study is how asteroid risk stacks up against other causes of death. The researchers compared the lifetime odds of dying from an asteroid strike to hazards ranging from carbon monoxide poisoning to elephant attacks.

Here’s where the context becomes interesting: while the probability of an asteroid larger than 140 meters hitting Earth is higher than that of being struck by lightning, it’s still far lower than dying in a car accident, from the flu, or even from a kitchen accident. In other words, the perceived risk of asteroid death is far greater than the actual risk — but that doesn’t mean we should ignore it.

The researchers also analyzed what happens when each hazard occurs. For example, elephant attacks and carbon monoxide poisoning have high fatality rates when they do happen, while smaller asteroid strikes often spare the vast majority of the population.

Why Planetary Defense Still Matters

If the odds are so low, why worry? Nugent and her team argue that asteroid defense is like insurance: the annual “premium” — in the form of detection systems, monitoring programs, and potential deflection missions — is small compared to the catastrophe it could prevent.

Recent advances show that humanity isn’t helpless. In 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) successfully altered the trajectory of a small asteroid, proving that a deflection strategy can work. While the target asteroid in that mission was never a threat to Earth, the experiment was a milestone in planetary defense technology.

The National Academies have echoed this sentiment, framing asteroid defense as a moral and strategic responsibility. As their report put it: “The committee considers work on this problem as insurance, with the premiums devoted wholly toward preventing the tragedy.”

A Risk Worth Understanding

Ultimately, this study is less about scaring the public and more about placing asteroid danger in a rational context. Most of us will never experience such a cosmic catastrophe, but the risk — however small — is real. And unlike lightning strikes or random accidents, asteroid impacts are one of the few natural disasters that humanity could prevent entirely, given enough warning and the right technology.

It’s a reminder that in the vast lottery of the cosmos, we can’t control which numbers are drawn — but we can prepare. Somewhere out there, millions of space rocks continue their silent journeys around the Sun. With vigilance, science, and global cooperation, we might just make sure they stay on their course — and out of ours.

More information: C. R. Nugent et al, Placing the Near-Earth Object Impact Probability in Context, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.02418