At the edge of human knowledge lies a realm so delicate, so fleeting, that even the most advanced instruments struggle to capture its secrets. This is the world of ultracold quantum gases—collections of atoms cooled to temperatures just above absolute zero, where the laws of classical physics collapse and quantum behavior comes to life.

In this strange domain, particles no longer act like tiny billiard balls but instead reveal their wave-like nature, overlapping and interacting in ways that defy ordinary intuition. For physicists, these ultracold systems are more than exotic curiosities. They are pristine laboratories, ideal for exploring how matter organizes itself at the most fundamental level and for testing theoretical models that could illuminate everything from superconductors to the very fabric of the universe.

Yet, as with all deep mysteries, there has been a barrier: how to see what is truly happening inside these quantum gatherings. Until recently, even the most precise tools left scientists peering through a fog. But a team at Heidelberg University has now devised a new way to lift that veil. Their breakthrough opens a window onto the microscopic structures hidden within ultracold gases, offering both clarity and wonder.

The Challenge of Seeing the Unseeable

For decades, physicists studying ultracold gases relied on a technique called single-atom–resolved imaging. This powerful method allowed them to detect and track individual atoms, mapping out correlations in their behavior. It was like having a camera that could pick out faces in a crowd.

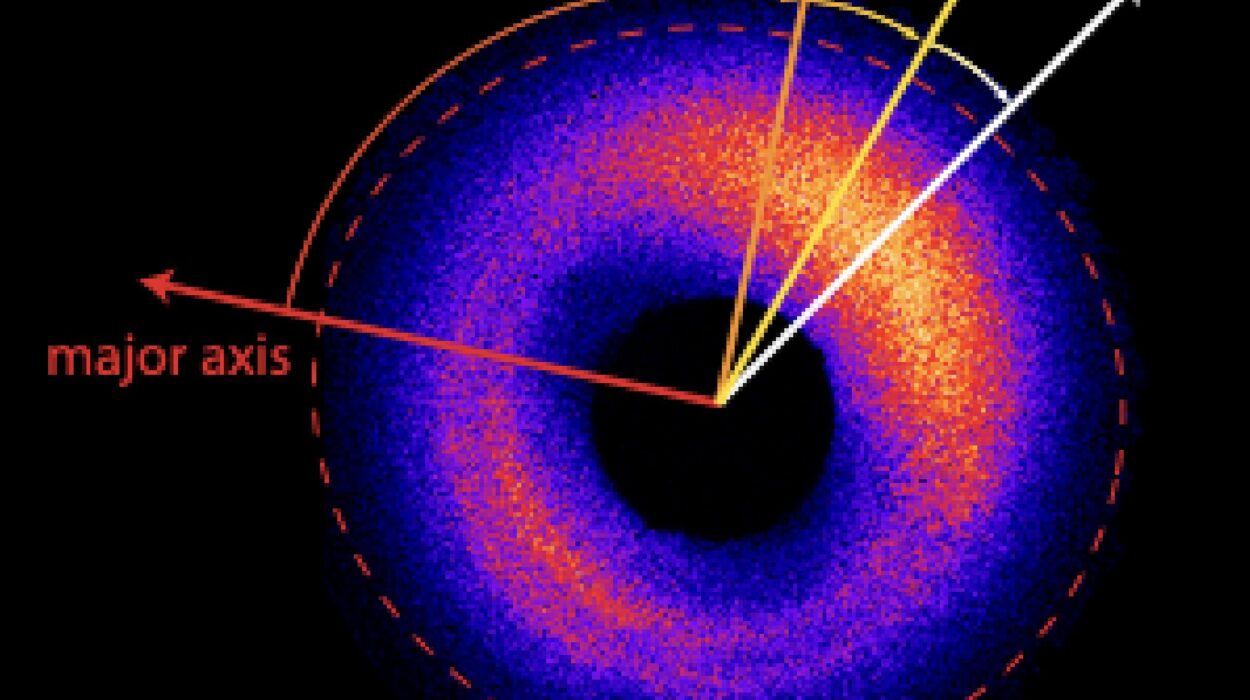

But there was a problem. The resolution of these images wasn’t sharp enough to capture the fine details of the atoms’ positions. Instead of a vivid picture of their arrangement, researchers often saw a blurred cloud—a featureless glow concealing the subtle structures they longed to study. The intricate interplay of forces and interactions remained hidden behind this curtain of limitation.

Sandra Brandstetter, a physicist at Heidelberg and first author of the new study, explained the frustration simply: without a way to magnify the atomic wavefunctions—the mathematical descriptions of the atoms’ quantum states—all one could see was a blob. The physics was there, but it was out of reach.

Turning Lasers into Quantum Lenses

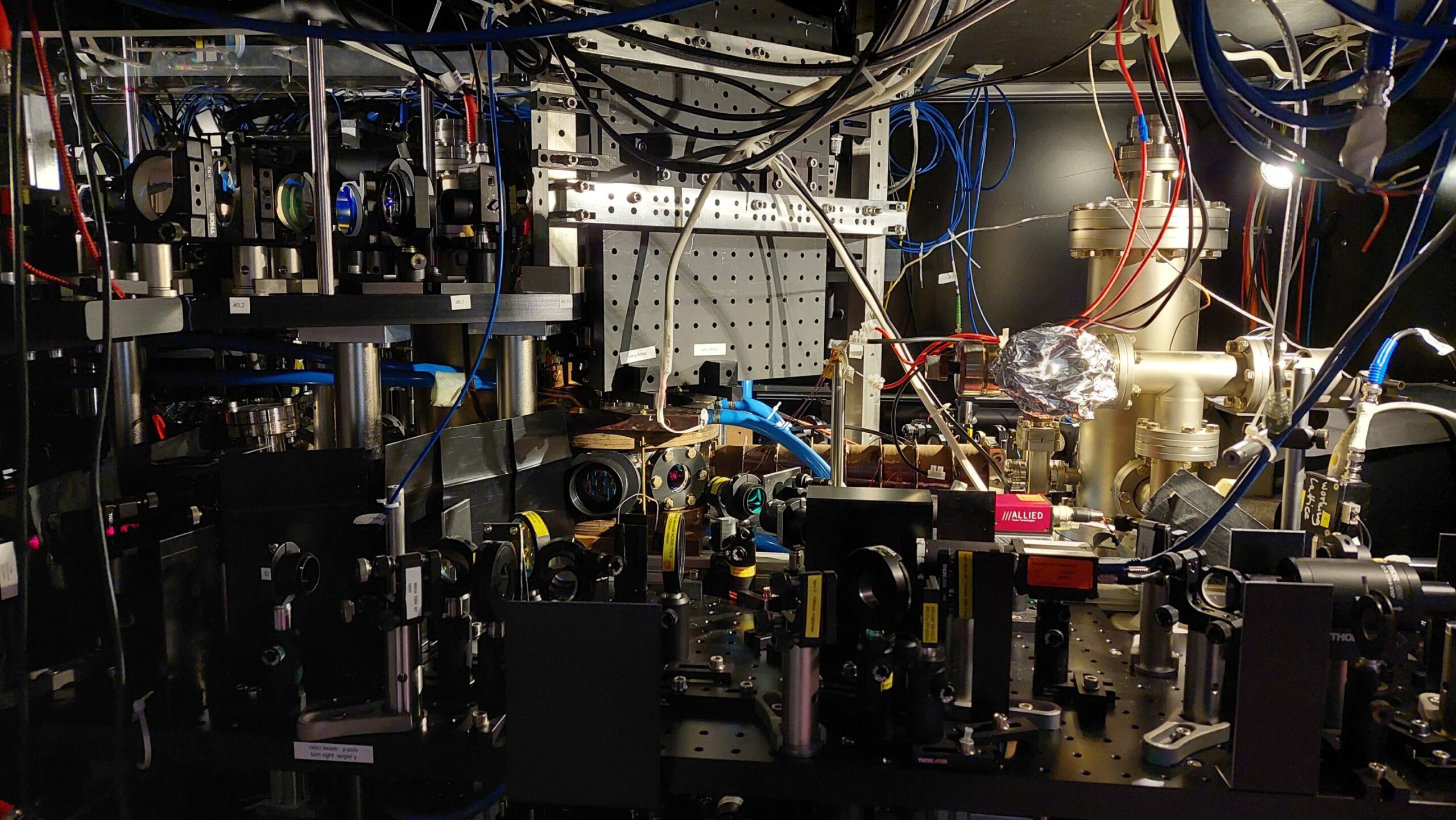

The solution devised by Brandstetter and her colleagues was as elegant as it was ingenious. Instead of glass lenses, they used carefully designed laser fields to manipulate the atoms themselves. These lasers acted like an optical magnifying glass—not by bending light, but by expanding the atoms’ wavefunctions in a controlled, measurable way.

In essence, they created a microscope for quantum matter. The atoms’ wave-like states could be stretched, magnified, and then captured with existing imaging techniques. Suddenly, details that had been blurred into invisibility came into sharp focus. Hidden spatial structures revealed themselves, as though an unseen landscape had been illuminated for the first time.

Just as with a real microscope, precision was key. Any misalignment could warp or distort the image. But with meticulous calibration, the team achieved a clean magnification that preserved the integrity of the system’s quantum features. What once looked like a fog now resolved into rich detail.

Putting the Method to the Test

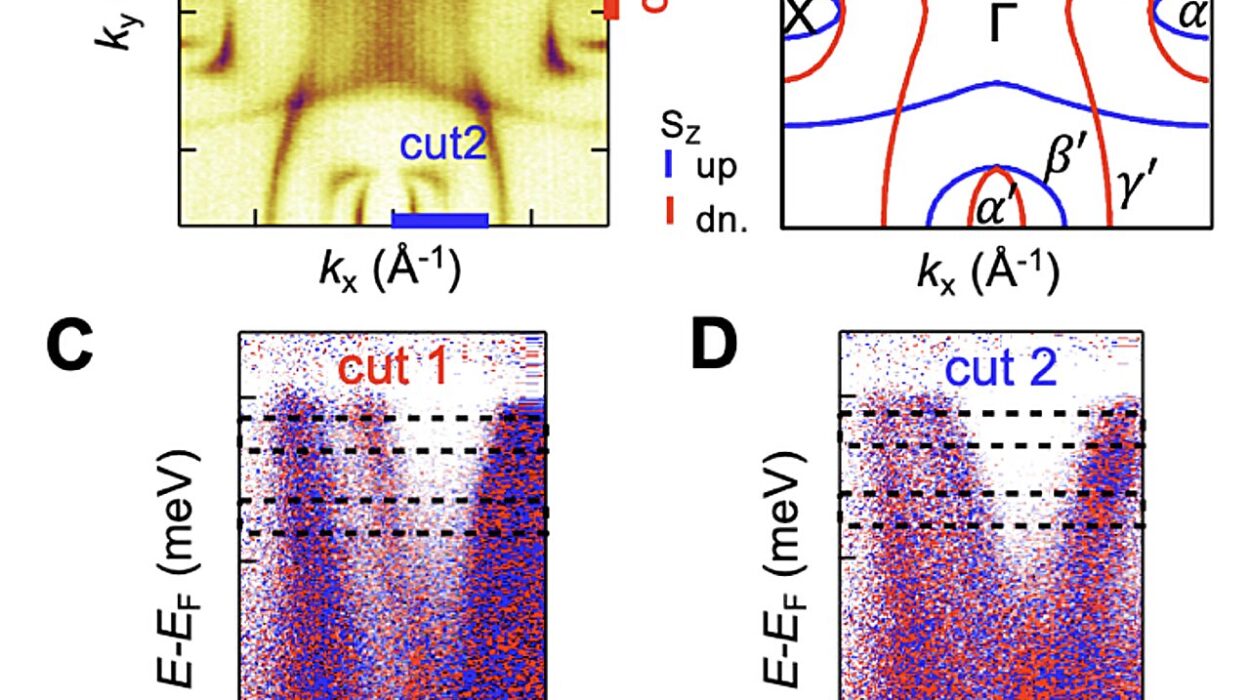

A bold idea is only as good as its results, and the Heidelberg researchers were determined to prove their technique’s power. They first applied their magnification method to systems whose behavior was already well-understood. In one experiment, they examined two interacting atoms; in another, they looked at six non-interacting fermions trapped in a harmonic potential.

The images they obtained matched theoretical predictions with striking accuracy. This was more than validation—it was a revelation. The magnification scheme had not only worked but had confirmed itself as a reliable new tool for exploring the quantum world. What was once theory could now be seen directly.

Opening Doors to Hidden Physics

The implications of this new imaging method stretch far beyond the experiments already conducted. Many researchers study atomic systems where interactions occur at scales too small for traditional imaging to resolve. For instance, systems involving dipolar atoms—particles that interact through long-range forces—often feature lattice spacings smaller than optical resolution allows. With the new magnification scheme, these once-inaccessible structures can now be observed in real space.

This is not merely a technical upgrade. It is a conceptual leap that bridges the gap between theory and experiment. For the first time, scientists can directly compare predictions about strongly interacting quantum systems with images that reveal their hidden geometries. The fog has lifted, and the map of the microscopic world has grown clearer.

Toward the Heart of Superfluidity

The Heidelberg team is already pushing forward into uncharted territory. One of their next goals is to use the method to study how fermionic atoms—particles that make up matter like electrons and protons—pair up. This pairing is the microscopic mechanism that underlies superfluidity, a state of matter where particles flow without resistance.

Understanding superfluidity isn’t just an abstract pursuit. It connects to some of the most profound questions in physics, from the behavior of neutron stars to the possibility of room-temperature superconductors. By watching atom pairs form in real time, both in momentum space and real space, physicists may gain unprecedented insight into one of nature’s most captivating phenomena.

A Bridge Between the Infinitesimal and the Immense

What makes this breakthrough so exhilarating is its resonance beyond the laboratory. The ability to magnify and resolve the wavefunctions of ultracold atoms ties into universal themes of science: the quest to see the unseeable, to make the invisible visible, to bring order to mystery.

From the swirling clouds of galaxies to the dense hearts of stars, the universe itself is a many-body system. The same principles that govern ultracold gases echo across scales, connecting quantum physics to astrophysics. In this sense, each breakthrough in imaging the smallest systems illuminates something about the largest.

The Human Dimension of Discovery

At its heart, this story is not just about lasers, atoms, or equations. It is about human curiosity and ingenuity. Faced with a barrier, researchers refused to accept blurred images as the final word. Instead, they borrowed inspiration from the familiar—optical microscopes—and reinvented it in the quantum domain.

Their achievement is a reminder that physics is not only about understanding the universe but also about expanding the ways we see it. Every new tool opens a new horizon, and every horizon invites deeper exploration.

A Future Filled with Possibilities

The Heidelberg team’s method has already proven itself, but its potential is just beginning to unfold. By allowing researchers worldwide to adopt this approach, the door is now open to a new era of precision studies in quantum physics.

From uncovering hidden patterns of strongly interacting particles to probing the mechanisms of superfluidity and beyond, this magnification technique could reshape how we explore the quantum frontier. It is an invitation to look closer, to see deeper, and to connect the dots between theory and reality.

In the end, the story of ultracold gases and their magnified wavefunctions is not just about atoms—it is about vision. It is about daring to look where others saw only a blur and discovering that, with the right lens, an entire hidden world comes into focus.

More information: Sandra Brandstetter et al, Magnifying the Wave Function of Interacting Fermionic Atoms, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/wdjr-m2hg. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2409.18954