For billions of years, Earth’s continents have stood as the unshakable platforms of life — vast, immovable foundations for mountains, forests, civilizations, and the endless dance of ecosystems. Yet beneath this stability lies a secret that has baffled scientists for more than a century. Why have Earth’s continents remained so enduringly solid while the ocean floor constantly renews itself? What invisible force forged these continents into lasting monuments of stone?

Now, scientists from Penn State and Columbia University have brought us closer than ever to the answer. In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Geoscience, they revealed a stunning truth: the key to the continents’ stability isn’t just in the rocks themselves — it’s in the heat that once shaped them.

Forged in Fire: The Heat That Built the Continents

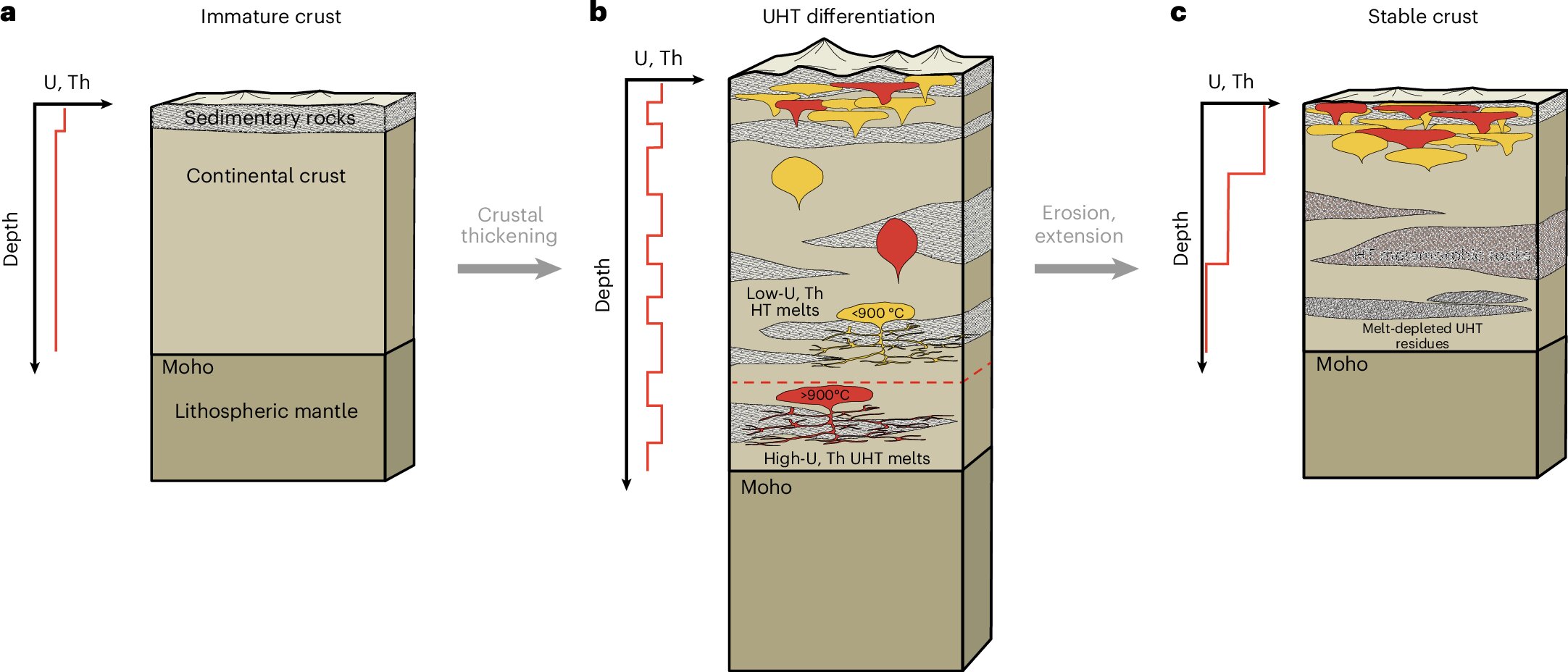

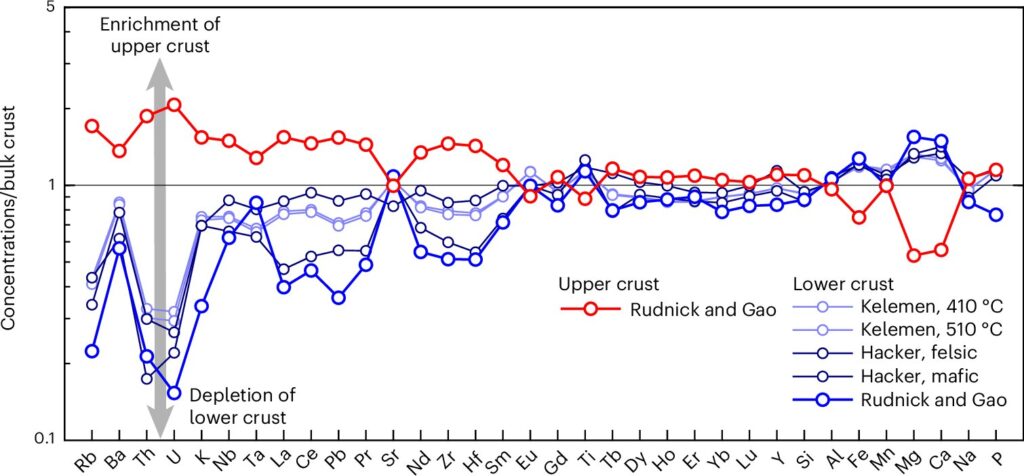

The research shows that to create the kind of continental crust that lasts billions of years, the lower crust must reach scorching temperatures above 900 degrees Celsius — nearly as hot as molten lava. It was this extreme heat that allowed radioactive elements like uranium and thorium to migrate upward, carrying their heat with them and cooling the deeper crust.

As the lower crust cooled, it grew stronger and more rigid, forming the solid base upon which continents could stand the test of time. This process, the scientists say, was the furnace that forged Earth’s stability — a geologic act of creation that made our planet’s surface suitable for life.

“Stable continents are a prerequisite for habitability,” said Andrew Smye, the study’s lead author and a geoscientist at Penn State. “But in order for them to gain that stability, they have to cool down. To cool down, they have to move all these elements that produce heat—uranium, thorium, and potassium—toward the surface.”

Without this heat transfer, the deep crust would have remained molten, unstable, and ever-shifting. Instead, Earth learned how to temper itself — to harden its shell like a blacksmith cooling steel after the forge.

The Planet That Learned to Cool

Continental crust as we know it — thick, silicon-rich, and long-lived — emerged around three billion years ago. Before that, Earth’s outer shell was younger, thinner, and more chaotic, constantly recycled by volcanic activity and tectonic upheaval.

For decades, scientists believed that melting pre-existing crust was essential to forming continents. But Smye and his colleague, Peter Kelemen of Columbia University, discovered that melting alone wasn’t enough. The crust had to overheat, reaching temperatures hundreds of degrees higher than previously thought.

“We basically found a new recipe for how to make continents,” Smye said. “They need to get much hotter than was previously thought — about 200 degrees hotter.”

Forging Continents Like Steel

To explain their discovery, Smye drew a vivid analogy. Imagine forging steel. The metal is heated until it becomes soft enough to reshape, yet not so molten that it loses structure. With every hammer blow, impurities are removed, and the metal’s internal structure realigns — growing stronger, tougher, more resilient.

In the same way, tectonic forces deep within the Earth acted like the hammer, while intense heat worked as the furnace. Together, they transformed ordinary crust into something extraordinary — continental crust strong enough to resist destruction for billions of years.

“The forging of the crust,” Smye said, “requires a furnace capable of ultra-high temperatures.”

Reading the Rocks: Evidence from Earth’s Oldest Materials

To test their ideas, the researchers analyzed rocks collected from the Alps in Europe and the southwestern United States — places where the Earth’s crust has been deeply buried and reheated during mountain formation. They also drew on hundreds of samples from across the globe, studying the chemical fingerprints left behind by ancient metamorphic processes.

They found a clear pattern: rocks that had melted above 900°C contained significantly less uranium and thorium than those that had melted at lower temperatures. This indicated that the radioactive elements had been driven out during intense heating, migrating upward through the crust.

“It’s rare to see such a consistent signal in rocks from so many different places,” Smye said. “It was one of those eureka moments — you realize nature is trying to tell us something.”

The Hidden Heat of the Early Earth

Billions of years ago, the Earth was far hotter than it is today. Radioactive decay within the planet’s crust produced about twice as much heat as it does now. This extra thermal energy provided the conditions necessary for the crust to reach ultra-high temperatures and undergo the “forging” process that stabilized the continents.

“There was more heat available in the system,” Smye explained. “Today, we wouldn’t expect as much stable crust to be produced because there’s less heat available to forge it.”

That means the continents we stand on — ancient, immense, and enduring — are products of a fiery past we can scarcely imagine. Their strength is a record of the planet’s youth, when Earth burned hotter and worked harder to shape itself into the cradle of life.

From Geology to Technology: The Modern Implications

This discovery is not just about the distant past. It has real implications for the modern world — especially for our search for critical minerals.

As radioactive elements like uranium, thorium, and potassium migrated through the crust billions of years ago, they carried other valuable elements with them — including lithium, tin, and tungsten. These rare earth elements, vital to modern technologies like smartphones, electric vehicles, and renewable energy systems, were concentrated in specific regions by the same geological processes that forged the continents.

Understanding how these elements moved and where they settled could help geologists locate new mineral deposits in the present day. “If you destabilize the minerals that host uranium, thorium, and potassium,” Smye said, “you’re also releasing a lot of rare earth elements.”

By retracing the ancient paths of heat and chemistry that shaped the continents, scientists might uncover new ways to meet the material demands of the modern age — sustainably and efficiently.

Lessons for Other Worlds

The implications of this study extend far beyond Earth. The processes that stabilized our continents may also operate on other rocky planets across the cosmos. If so, planetary scientists can use these findings as a guide in the search for habitable worlds.

Stable continents are not just geological curiosities — they are essential for life. Without stable landmasses, oceans would dominate, climates would fluctuate wildly, and ecosystems would struggle to endure. The cooling and hardening of a planet’s crust may be one of the crucial steps in making it a home for life.

“Our results suggest that the processes that created Earth’s stable continents could happen elsewhere,” Smye said. “That gives us a new way to think about planetary habitability — what signs to look for, and what makes a planet truly Earth-like.”

A Planet Forged to Last

The continents beneath our feet tell a story of transformation — of fire, pressure, and time. They remind us that stability is not born from stillness but from struggle. The same forces that tore the young Earth apart also forged it into something enduring.

When we walk across ancient mountain ranges or touch rocks that have stood for billions of years, we are touching the legacy of that great planetary forge. The continents are the cooled scars of a once-fiery world — and without them, neither life nor civilization would exist.

The Eternal Dance of Heat and Stone

Even now, the Earth is not done changing. Deep beneath us, the mantle still churns, and the crust still bends and breaks. Mountains rise and erode, continents drift and collide. Yet through it all, the ancient foundations remain — strong, silent witnesses to the heat that once shaped them.

The story of Earth’s continents is, in the end, the story of transformation. It is the story of a world that learned to forge itself — not into perfection, but into endurance. From fire came form; from chaos, stability.

And in that stability, life found a place to begin.

More information: Andrew J. Smye et al, Ultra-hot origins of stable continents, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01820-2