In a quiet lab at Northeastern University, something extraordinary happened—something that could redefine the speed limits of electronics as we know them.

A team of physicists has discovered a way to flip the electronic behavior of a material on command, transforming it from an insulator into a conductor—and back again—at unprecedented speeds and with lasting stability. The implications? Computers, phones, and other devices that could become a thousand times faster and exponentially more efficient than anything on the market today.

“We’re talking about going from gigahertz to terahertz,” said Alberto de la Torre, assistant professor of physics and lead author of the research, published in Nature Physics. “It’s not just an improvement—it’s a fundamental leap in how we design and use electronics.”

Flipping the Switch—With Heat and Light

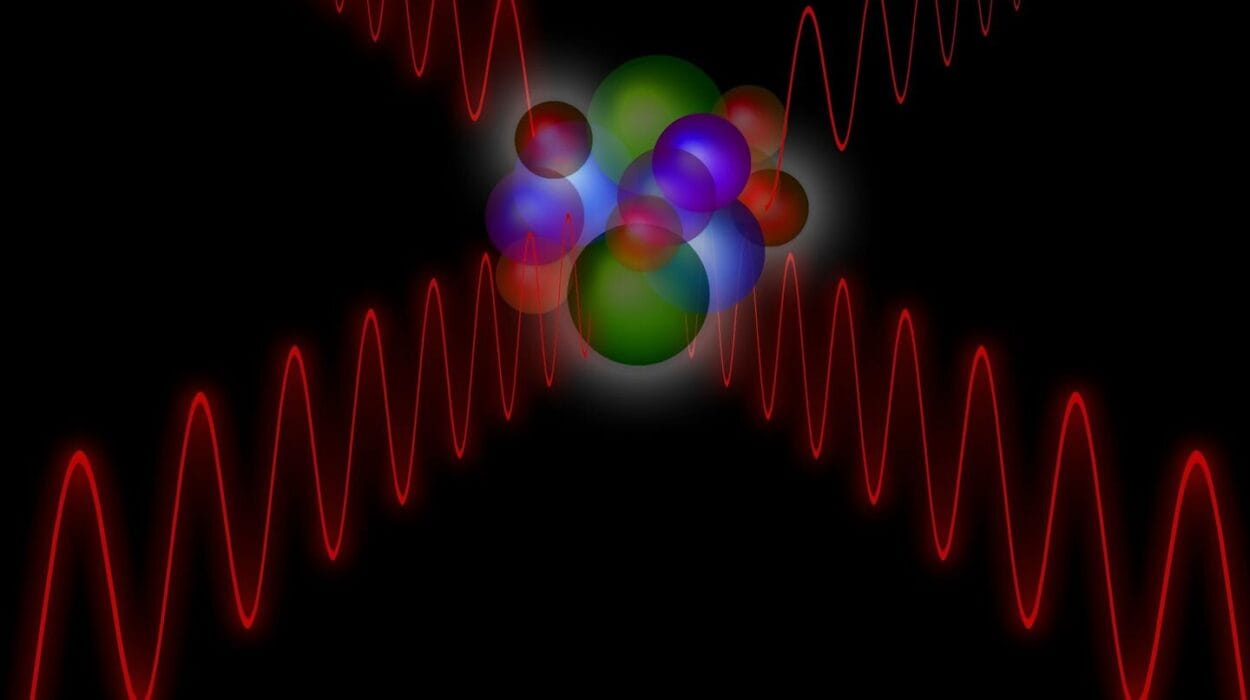

At the heart of this discovery lies a technique the researchers call thermal quenching. By carefully heating and then rapidly cooling a special quantum material known as 1T-TaS₂, the team can trigger a phase shift in its electronic state. One moment, the material behaves like an insulator. The next, it becomes a metallic conductor.

What makes this even more remarkable is how the transformation can be reversed instantly. And unlike previous experiments that required extreme, cryogenic temperatures, this new metallic state remains stable at close to room temperature—for months.

“It’s like creating a light switch made out of the material itself,” said Gregory Fiete, co-author of the study and professor of physics at Northeastern. “But instead of flipping a plastic switch on your wall, you’re using light and temperature to change the very nature of the material.”

One Material to Rule Them All

Silicon has long been the workhorse of modern electronics. From microprocessors to memory chips, it’s been the backbone of our digital age. But as engineers have pushed it to its limits—stacking components in three dimensions, miniaturizing them to atomic scales—the material is showing signs of strain. Heat buildup, power consumption, and physical limits are all barriers to continued advancement.

This new research offers a bold alternative. Instead of building devices from separate conductive and insulating materials, engineers could use a single programmable quantum material—one that can switch roles on demand, controlled by light and temperature alone.

“We eliminate one of the biggest engineering hurdles,” Fiete said. “Instead of stitching together different materials and managing their interfaces, we use one material and manipulate it directly. That simplifies everything.”

The Hidden Power of Light

Previous attempts to manipulate materials this way have relied on ultrafast laser pulses, achieving temporary changes that lasted mere fractions of a second—and only at freezing temperatures. This breakthrough extends the effect not just in time, but in practicality. Now, everyday temperatures are enough to hold the altered state for months.

“Everyone who has ever waited for a video to load or a file to save has felt the drag of electronic limitations,” said Fiete. “There’s nothing faster than light. And now, we’re using light to control matter at the fastest scale allowed by the laws of physics.”

When the team shone light onto 1T-TaS₂, they induced what’s called a “hidden metallic state”—a condition that had previously only existed under laboratory extremes. But now, using their technique, that state becomes accessible, stable, and, perhaps most importantly, useful.

Why This Matters for the Future of Electronics

From quantum computing to neuromorphic chips, researchers worldwide are chasing new frontiers in materials science. The goal isn’t just faster computers—it’s smarter, smaller, more sustainable ones. Silicon is dense, expensive to fabricate, and reaching the end of its scalability. Quantum materials like 1T-TaS₂ open the door to a new paradigm.

“Instead of cramming more transistors into the same space, what if we made the materials themselves smarter?” de la Torre said. “What if your processor didn’t just conduct electricity—but knew when and how to conduct it?”

This discovery pushes that idea closer to reality. The ability to change a material’s behavior at will, in real time, and at usable temperatures, could enable electronics that operate at terahertz frequencies—orders of magnitude faster than current devices.

That means real-time data processing, ultra-fast memory access, and radically reduced energy usage. For consumers, it could translate into instant-loading applications, super-efficient AI chips, and revolutionary leaps in cloud and edge computing.

Not Just a Scientific Curiosity

Make no mistake—this isn’t an esoteric lab trick. The researchers believe this discovery is a foundational tool for the future of electronic design. And they’re not alone. Across the field of condensed matter physics, control over material phases is viewed as a golden key.

“One of the grand challenges in physics is how to control material properties on demand,” Fiete said. “That’s the holy grail. And we’re getting closer.”

The long-term vision? Smart chips that configure themselves in real time. Memory systems that store data with light. Machines that don’t just use electricity—but actively reshape the pathways it travels.

“We’re at a point where, in order to keep pushing performance forward, we need a new way of thinking,” Fiete added. “And this—this is a new way.”

The Road Ahead

While this breakthrough is thrilling, challenges remain. The technology needs to be scaled, integrated into real-world systems, and tested across many scenarios. But the groundwork is laid.

From the outside, it may look like a small shift—a glimmer of light, a flash of heat—but what’s happening inside this quantum material is nothing short of transformational.

In the coming years, this discovery could catalyze a new age in electronics—one defined not by wires and silicon, but by light, speed, and atomic precision.

For now, the world watches—and waits—for what comes next.

Reference: Alberto de la Torre et al, Dynamic phase transition in 1T-TaS2 via a thermal quench, Nature Physics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41567-025-02938-1. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2407.07953