In the heart of Kyoto, a group of researchers recently made a discovery that sends a ripple of excitement through the world of food science and ancient history. Imagine a time long before modern winemaking techniques—before laboratory yeast cultures and controlled fermentation processes—when people relied on nature to create one of humanity’s oldest beverages. What if the answer to how our ancestors made wine was simpler, yet more profound than we ever realized?

This was the exact question that inspired a team from Kyoto University to investigate an age-old mystery: Could raisins, dried by the sun, have been used by ancient peoples to produce wine?

The Mystery of Ancient Wine Production

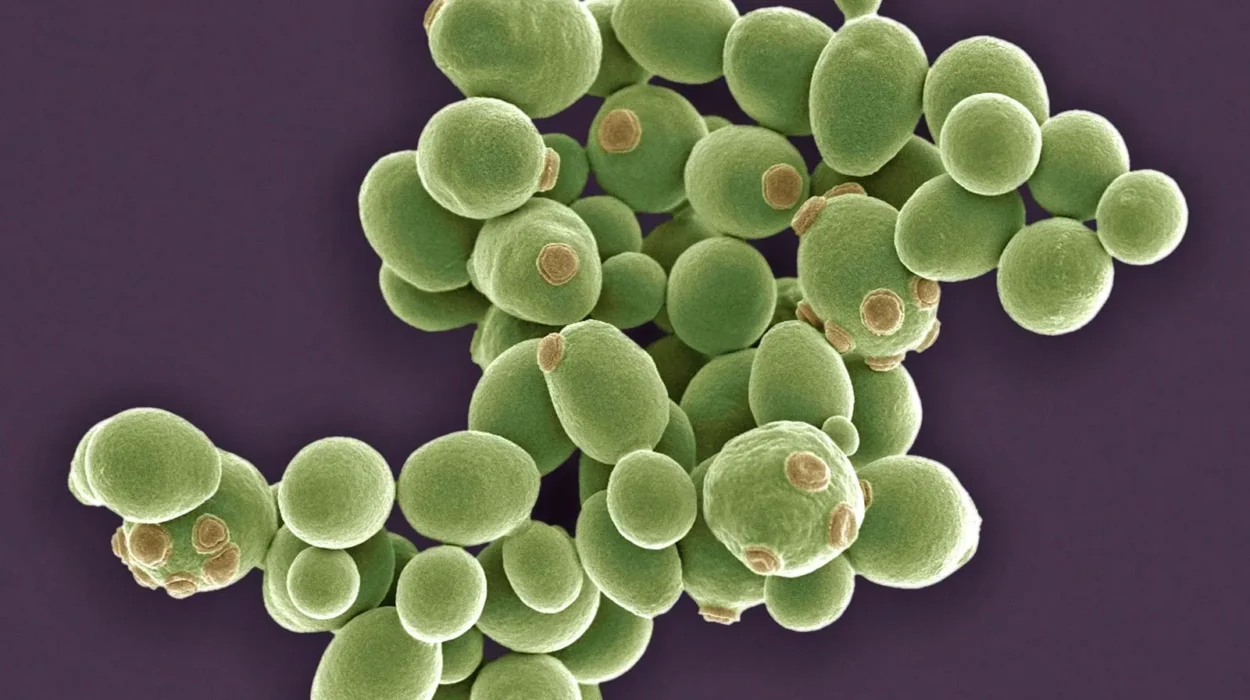

For centuries, historians have wondered how early humans fermented fruit into alcohol without the advanced knowledge of microbiology and chemistry that we have today. Modern wineries typically rely on Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the famous yeast that is central to the fermentation process that creates alcohol. But the mystery deepens when we look at the grapes that were used in early winemaking. Surprisingly, S. cerevisiae is rarely found on grape skins, suggesting that fresh grapes may not have been the key ingredient for fermentation. Could our ancient ancestors have had a different, yet equally effective method?

Enter the humble raisin.

In a previous study, the Kyoto University team discovered that S. cerevisiae was abundant on raisins. This finding led them to a fascinating hypothesis: could ancient wine producers have used dried fruit, like raisins, for fermentation instead of fresh grapes? After all, raisins are not only easy to store but also have the potential to carry a wealth of microorganisms that might facilitate fermentation.

A Step Back in Time: Testing the Raisin Theory

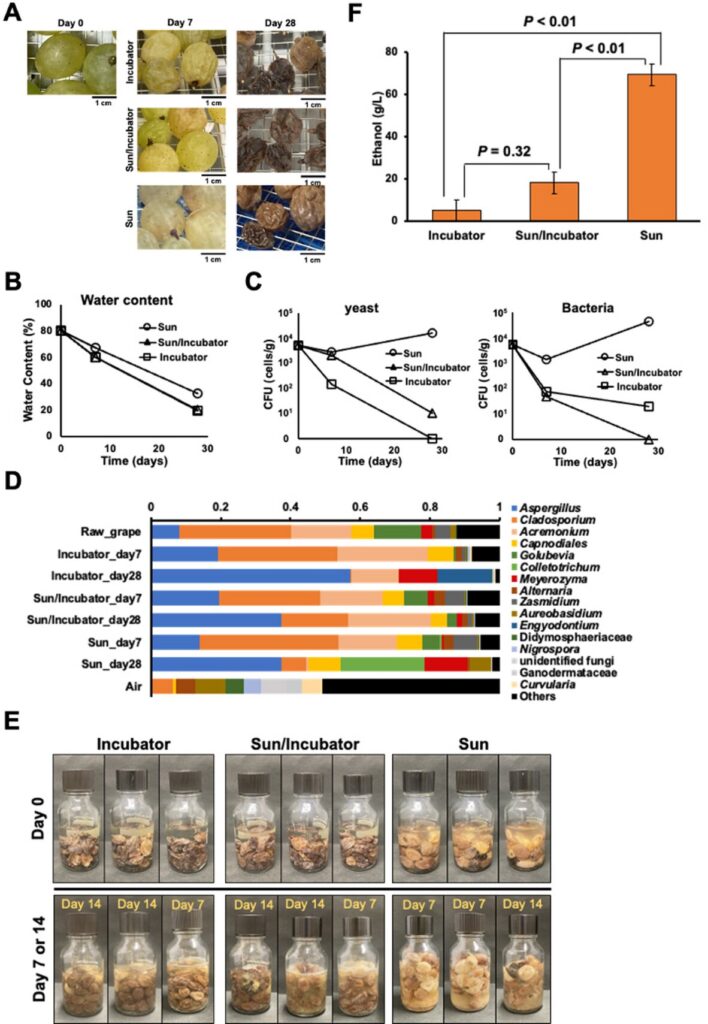

With this theory in hand, the researchers embarked on an experiment that would reveal the natural magic behind sun-dried raisins. Their approach was both simple and ingenious. They collected fresh grapes from a local orchard and dried them in three different ways: in an incubator, through sun-drying, and a combination of both methods. After drying for 28 days, they submerged the raisins in water and stored them at room temperature for two weeks.

Three separate samples were created for each drying method to account for variability, and the researchers eagerly awaited their results.

When the team finally analyzed the outcome, the findings were as clear as the wine that would soon be produced. The sun-dried raisins were by far the most successful in producing fermentation. All three samples of sun-dried raisins that had been soaked in water yielded significant alcohol concentrations, confirming that the sun-drying process was not only effective in colonizing the raisins with yeast but also in facilitating fermentation.

While the incubator-dried and combined drying samples showed some promise, only a few of those samples fermented successfully. In contrast, the sun-dried raisins consistently delivered higher ethanol levels. This finding suggests that sun-drying is the key process that makes raisins ideal for fermentation—a natural step that could have been harnessed by ancient civilizations.

A Look Inside the Science of Fermentation

What the researchers discovered goes beyond just wine. Their study sheds light on the natural fermentation mechanisms that microorganisms, such as yeasts, can facilitate. “By clarifying the natural fermentation mechanism that various microorganisms facilitate at the molecular level, we’d like to connect our study to the creation of unique alcoholic beverages,” said first author Mamoru Hio. This suggests that our ancestors, without the advanced tools of modern science, may have already been able to create alcohol in ways that we are only now beginning to fully understand.

The study also found that, in successful samples, the diversity of species of microorganisms decreased over time. However, the abundance of alcohol-fermenting yeasts, like S. cerevisiae, grew significantly. This implies that these yeasts were the dominant players in the fermentation process, a fascinating insight into how nature can regulate microbial ecosystems to promote alcohol production.

The Quest for Deeper Understanding

But while the results of this experiment were promising, they also raise new questions that scientists are eager to answer. How do the yeasts migrate from the environment to the raisins during the drying process? The study’s authors were careful to point out that this is still an unanswered question.

Additionally, the study was conducted outside of traditional raisin-producing regions, in a location that may not fully represent the natural climate conditions where ancient winemaking took place. To replicate the conditions more accurately, future research will need to focus on regions with dry climates, as these are more similar to the environments where ancient peoples may have dried their fruit.

“We aim to uncover the molecular mechanism behind this interaction between microbial flora and microorganisms that reside in various fruits, including grapes,” said team leader Wataru Hashimoto. Their goal is not just to understand ancient wine production, but to explore how natural fermentation could be harnessed to create new food products and reduce food waste.

The team also pointed out a small, but important detail: the method only works with sun-dried raisins that are untreated. Most commercially available raisins are coated with oil to prevent sticking, and this oil coating inhibits fermentation, showing just how crucial it is to use raisins in their purest, most natural form for this process.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research is more than just a historical curiosity. It opens up exciting possibilities for the future of food production. Understanding the natural fermentation processes that occur in fruits could lead to the development of new types of beverages and food products, potentially reducing our reliance on artificial additives and synthetic processes.

Moreover, the study highlights the extraordinary ingenuity of ancient peoples. Far from being primitive or uninformed, they may have intuitively harnessed natural processes in ways that are only now being rediscovered by modern science. The ability to turn simple raisins into wine through natural fermentation demonstrates a profound understanding of nature and a resourcefulness that continues to inspire today.

As researchers like Hio and Hashimoto continue to delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms behind fermentation, we may find that our ancestors were not only ahead of their time—they were in perfect harmony with the natural world, crafting products from nature’s bounty in ways that we are just beginning to understand.

The next step is clear. Scientists are eager to study how microbial interactions shape the fermentation process and how this knowledge can be applied to create sustainable and innovative food solutions. In this sense, what started as a simple curiosity about raisins may very well lead to breakthroughs in both food science and sustainability.

And so, the next time you look at a raisin, you might just wonder: Could this tiny, dried fruit have been the key to an ancient tradition that still shapes our world today?

More information: Mamoru Hio et al, Spontaneous fermentation of raisin water to form wine, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-23715-3