At first glance, Segue 1 hardly seems like something that should rewrite astronomy textbooks. It is faint, sparse, and fragile-looking — a dwarf galaxy so insubstantial that astronomers once wondered how it had not already dissolved into the void. Its stars are few and widely scattered, not nearly enough to generate the gravity required to keep them bound together. For decades, the only plausible explanation seemed to be one of the great invisible forces of the cosmos: dark matter. The assumption was simple — there must be a massive halo of unseen matter cradling those few stars.

That assumption has now been shattered.

A new study from the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Texas at San Antonio has uncovered a startling different culprit for Segue 1’s survival: not dark matter, but a giant black hole. A monster, hundreds of thousands of times more massive than our sun, sits at the center of this tiny, ghostlike galaxy — and its gravity alone is what keeps Segue 1 from dissolving into space. This finding does more than solve a puzzle. It challenges one of the most widely held beliefs about dwarf galaxies and the role of dark matter in shaping them.

A Finding That Changes the Mental Blueprint of the Cosmos

For decades, astrophysicists have built their models of galaxies — especially small ones — around dark matter. Dwarf galaxies in particular were seen as little laboratories for dark matter research: tiny collections of visible stars embedded in enormous cocoons of invisible mass. If Segue 1 does not require that invisible mass to hold itself together, the premise is suddenly and profoundly destabilized.

Nathaniel Lujan, a UTSA graduate student and lead author of the new study, put it bluntly: astronomers may have been modeling these objects wrong. Instead of assuming that dwarf galaxies need dark matter, they may need to start treating supermassive black holes as the central architects.

A single dwarf galaxy — small enough to drown in the Milky Way’s light — has forced researchers to rethink how one of the most common types of galaxies in the universe might form and evolve.

Science Born in a Classroom, Proven on a Supercomputer

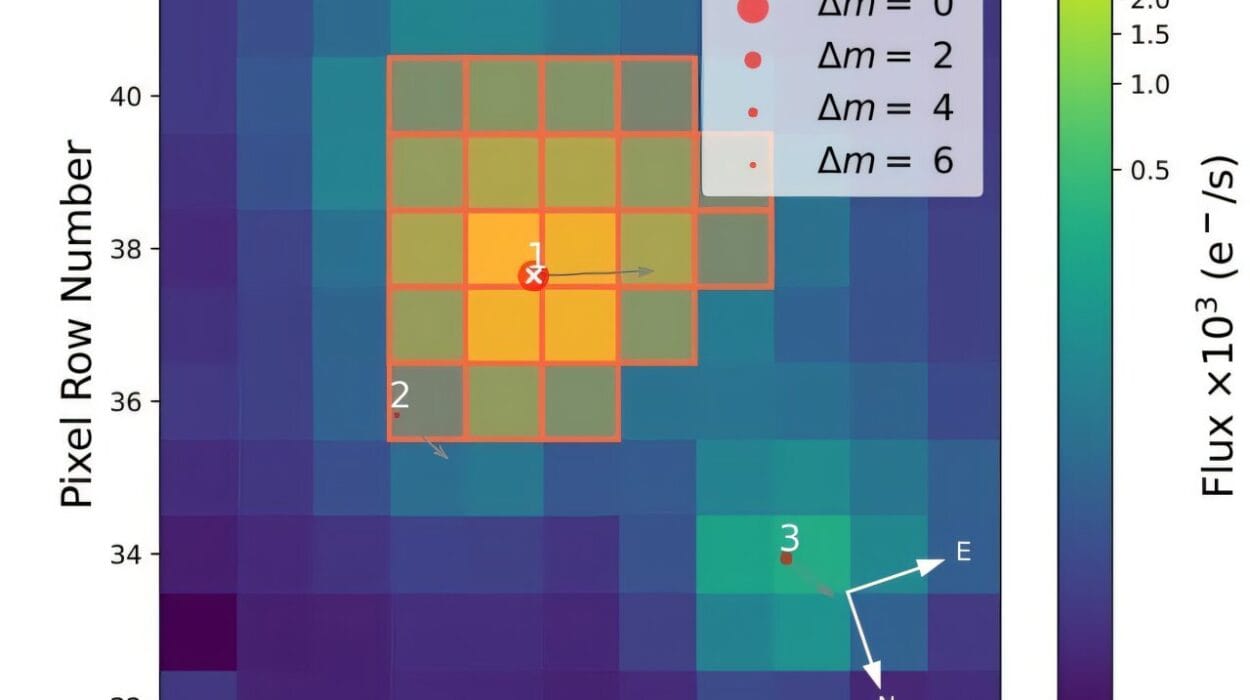

This discovery did not come from a high-budget international consortium or a decades–long mission, but from a university class — a collaboration between UT Austin and UT San Antonio where students were tasked with modeling the gravitational behavior inside Segue 1. Under the guidance of astrophysicists Karl Gebhardt and Richard Anantua, students harnessed the computing might of UT Austin’s Texas Advanced Computing Center to build hundreds of thousands of possible models.

Each digital scenario tested different cosmic arrangements: a galaxy held together by dark matter alone, a galaxy anchored by a massive black hole alone, and hybrids of both. The goal was simple — find which model predicted star movements most accurately.

Only one configuration matched the real star motions captured by Keck Observatory: a galaxy glued together by a central black hole, not dark matter.

Like many breakthroughs in science, what began as an exercise ended in revelation.

The Milky Way Is Tearing It Apart While the Black Hole Holds It Together

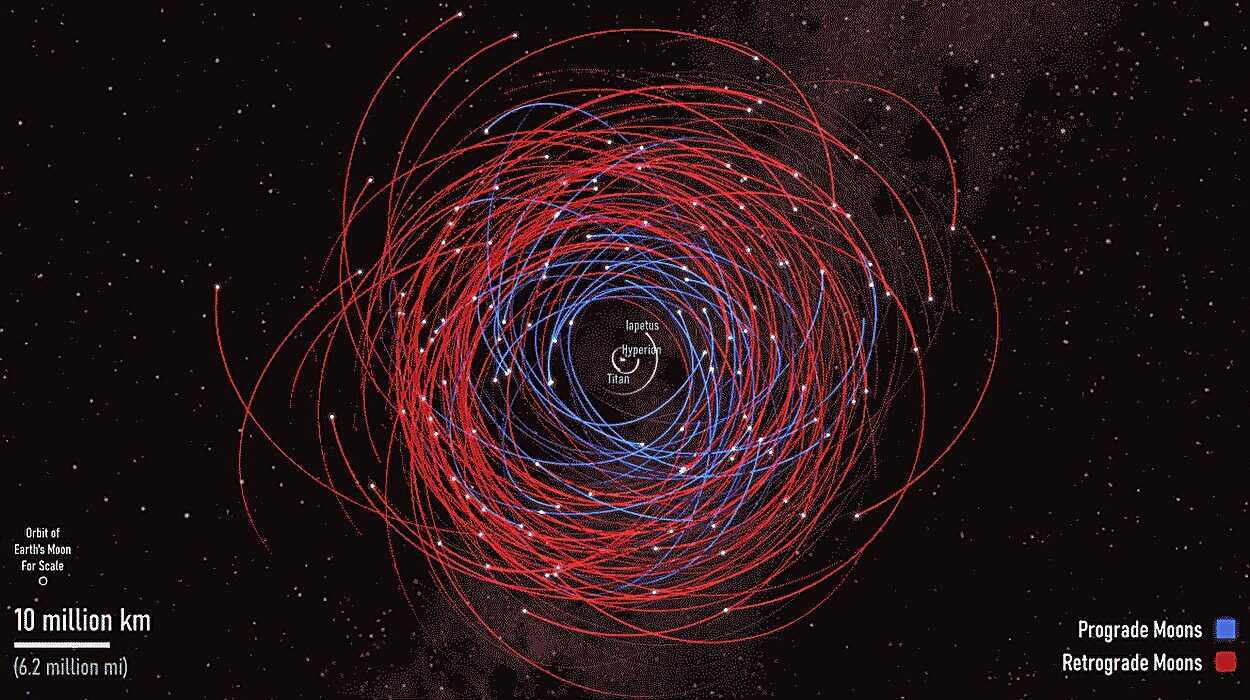

Segue 1 orbits just 75,000 light-years from us — nearly a galactic neighbor. And that proximity adds another layer to its drama. The Milky Way is slowly stripping Segue 1 of its stars in a process known as tidal stripping, pulling them out like threads from a fraying fabric.

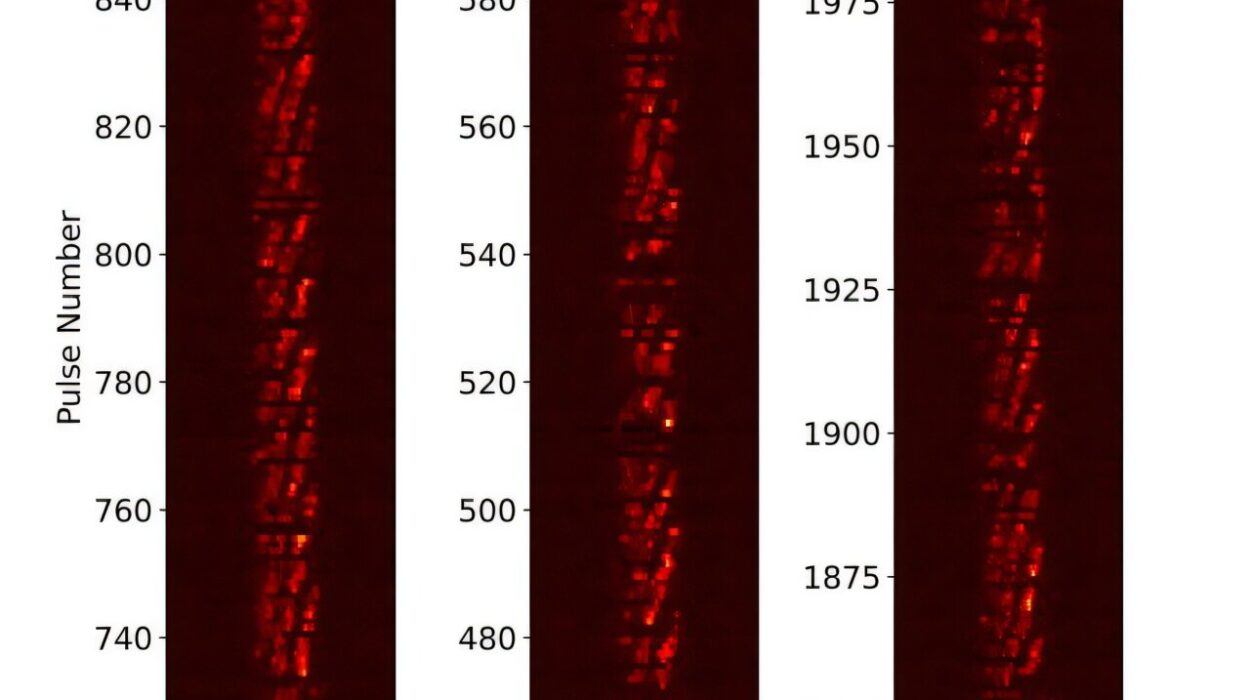

To isolate what truly belonged to Segue 1, students first had to subtract the stars escaping toward the Milky Way. When they analyzed the remaining, gravitationally loyal core, a striking pattern emerged: the inner stars were orbiting in tight, fast curves — the gravitational fingerprint of a massive black hole.

Dark matter–based expectations failed to reproduce this pattern. The reality was simpler and stranger: a single invisible object, vastly denser than all of Segue 1’s stars combined, was dictating the galaxy’s fate.

A Black Hole That Breaks the Rules

Most central black holes in galaxies obey a cosmic proportionality rule: their masses are typically smaller than, or roughly in tune with, the total stellar mass of their host galaxies. Segue 1 defies that principle outright.

Its black hole is estimated to be about 450,000 solar masses — ten times heavier than the mass of all the stars orbiting it. This imbalance is so extreme that if it turns out to be common in other small galaxies, then much of what astronomers think they know about galaxy evolution may be built on fragile ground.

Karl Gebhardt emphasizes the significance: a relationship once treated as law may actually be an exception.

A Remnant, a Relic, or a Window into Cosmic Childhood?

The discovery raises profound questions about Segue 1’s past. One possibility is that it used to be a much larger galaxy — one that was gradually harvested by the Milky Way, leaving behind only the stars strong enough to resist. If true, Segue 1 might be the fossil core of a once–thriving system.

Another possibility is more exotic and more tantalizing. Perhaps Segue 1 belongs to a class of galaxies known as Little Red Dots — recently discovered compact galaxies in the far, early universe that contain enormous black holes and very few stars. Because they lie at extreme distances, studying them directly is nearly impossible. Segue 1 might be the closest, clearest case study available — a living fossil from an earlier era of galaxy formation where black holes formed first, and stars followed sparsely.

Either scenario forces a revision of how galaxies — particularly small ones — come to be.

The Humbling Moral Written in Starlight

Segue 1 is almost physically insignificant — a barely-there smudge on the map of the sky. Yet it may overturn some of the most entrenched assumptions in modern astronomy. A galaxy too small to hold itself together turns out to be anchored by one of the most powerful objects in nature. A classroom exercise becomes a challenge to the prevailing cosmological model. A faint, dying satellite galaxy becomes a window into cosmic childhood or cosmic cannibalism.

Astronomy is full of grand images: vast spiral arms, glowing nebulae, roaring quasars. But sometimes, revolution arrives in something so dim you could miss it entirely with a glance.

Segue 1 reminds us that the universe does not owe us simplicity. Sometimes the smallest things contain the deepest surprises — and a whisper of stars around a hidden abyss can force humanity to rewrite what it thinks it knows about the structure of everything.

More information: Nathaniel Lujan et al, Modeling the “Dark-matter Dominated” Dwarf Galaxy Segue 1 with a Supermassive Black Hole, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae0b4f