In the soft glow of dawn, a woman wakes in a sunlit bedroom. Her partner stirs beside her, breathing softly. But before kissing him good morning, before letting the warmth of the sun fill her chest, her hand slides under the pillow and finds her phone. One thumb flick—and the day has begun.

First Instagram. Then Twitter. Then email. Her brain surges with a kaleidoscope of updates: a friend’s engagement, a celebrity scandal, a breaking-news alert about a war half a world away. It’s a hit of dopamine, like a gambler pulling a slot machine lever, not knowing what reward might tumble out. It’s just enough to keep her scrolling, scrolling, scrolling.

This scene plays out in bedrooms, kitchens, subways, bathrooms, boardrooms. It’s invisible and silent, yet all around us. Like vines creeping along a wall, technology has woven itself into our neural circuits, transforming the way we think, feel, and exist.

A century ago, humans learned to harness electricity. Today, electricity harnesses us.

The Spark Behind the Screen

The human brain is, in many ways, an ancient machine. Its architecture was molded over hundreds of thousands of years to keep us alive on savannahs and forests. The rush we feel upon finding fresh berries or hearing a twig snap in the darkness is rooted in neural circuits built for survival. But in the 21st century, we live in an entirely new ecosystem: an information jungle where the predators are notifications, the prey our attention.

When Steve Jobs stood on stage in 2007, holding the first iPhone like a glittering talisman, few could foresee how deeply this glass rectangle would sink its hooks into human consciousness. It would become an extension of the self, a mirror for the ego, a vessel for every curiosity or fear.

Apps, designed by teams of behavioral scientists, learned how to hack the human brain. They discovered that unpredictability was intoxicating—that we crave variable rewards the way rats crave sugar pellets. A like. A retweet. A heart emoji. Each one is a tiny spark in the reward centers of the brain. As the psychologist B.F. Skinner discovered decades ago, the most powerful way to shape behavior is through random rewards. Tech companies didn’t just learn this lesson. They built empires on it.

The Dopamine Rush

When you hear the ping of a message or the vibration of an incoming call, your brain releases a surge of dopamine. This neurotransmitter doesn’t simply produce pleasure—it drives motivation. Dopamine whispers: “Pay attention. This might be important.” The mere anticipation of a reward can be more potent than the reward itself.

This was once helpful. A burst of dopamine kept our ancestors vigilant for food, mates, and threats. Now it pushes us to check WhatsApp during dinner, to scroll TikTok in the bathroom, to binge YouTube videos until 3 a.m. The modern digital environment is a dopamine superhighway—blindingly fast, infinite in supply.

Neuroscientist Anna Lembke, author of Dopamine Nation, warns that overexposure to pleasure triggers can leave the brain in a state of chronic deficit. The brain compensates for overstimulation by reducing dopamine receptors or producing less dopamine. Over time, we require more and more stimulation to feel the same spark. Eventually, the absence of our digital fix can leave us anxious, restless, even depressed.

In the lab, brain scans show that people addicted to social media display similar neural activity to those addicted to substances like cocaine or heroin. The nucleus accumbens—a region associated with reward—lights up in both cases. Cravings emerge. Self-control dissolves.

We are chasing highs, and the chase is rewiring our minds.

The Attention Economy

Every day, humans generate 328 million terabytes of data. We upload 500 hours of video to YouTube every minute. Over 95 million photos flood Instagram daily. This is not just content—it’s currency in the new economy, traded for human attention.

Tristan Harris, former Google Design Ethicist, calls this “the attention economy.” Apps compete not merely for our time but for our cognitive real estate. The longer we scroll, the more ads we see, the more data they collect, the more profit they reap.

To win this war, tech companies deploy armies of engineers to craft frictionless designs: infinite scrolls that have no bottom, autoplay videos that erase decision fatigue, notification badges that pulse like neon lights. Even the color red was chosen for notifications because it triggers urgency and anxiety.

Our minds are the battlefield. We have become products, sold to the highest bidder. As Harris says, “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.”

Neuroplasticity’s Double-Edged Sword

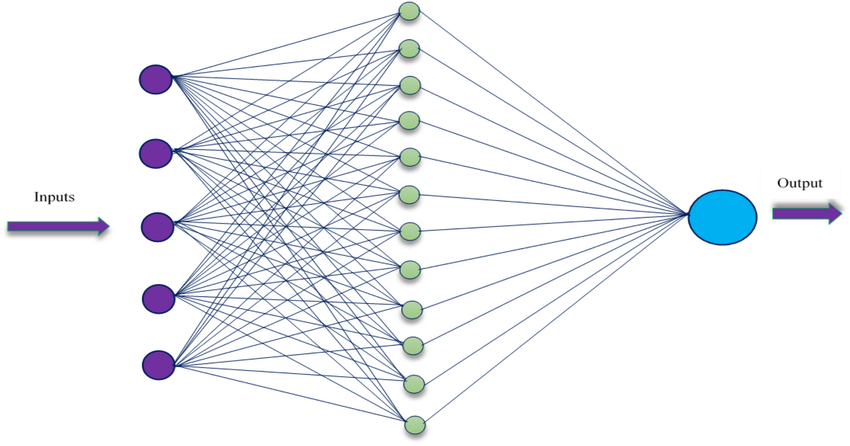

Our brains are marvels of adaptability. This property, known as neuroplasticity, is what allows a pianist to memorize concertos or a taxi driver to navigate city streets. New connections form; old ones fade. The architecture of the brain is constantly sculpted by experience.

Yet neuroplasticity cuts both ways. Just as practice can build skills, repeated digital behaviors can mold pathways that entrench distraction, compulsive checking, and shallow processing.

Studies show that frequent multitasking with devices weakens the brain’s prefrontal cortex—the seat of decision-making, impulse control, and focus. People who juggle apps and notifications often show reduced gray matter density in regions linked to empathy and emotional regulation.

The consequences ripple outward. Attention spans shrink. Memory grows porous. Our capacity for sustained thought, for “deep work,” fades. Nicholas Carr, in his haunting book The Shallows, warns that the internet is training us to skim rather than contemplate. “What the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation,” he writes. “Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”

We are not merely distracted. We are being transformed.

The Phantom Vibration Syndrome

For some, the consequences of tech addiction are visible, even physical. A startling number of people report “phantom vibration syndrome”—the eerie sensation that your phone is buzzing in your pocket when it’s not there at all. It’s the brain’s way of conjuring a stimulus it expects.

In hospitals and universities, researchers document the rise of digital withdrawal symptoms: anxiety, restlessness, even panic attacks when separated from devices. One study found that young people deprived of their phones for 24 hours reported feelings similar to those quitting nicotine or opioids. They described it as losing “a part of themselves.”

The phone has become a prosthetic organ, not merely a tool. To lose it, even briefly, is to lose a piece of one’s identity.

Social Media and the Mirror of Self

Social media presents a particularly insidious challenge. It offers us a mirror in which we craft idealized versions of ourselves. We become curators of our own museum exhibits, choosing the flattering angles, the sun-drenched vacations, the perfect witty caption.

But as we scroll through other people’s highlights, we are haunted by the suspicion that everyone else is happier, wealthier, more fulfilled. Psychologists call it “social comparison theory”—the tendency to measure our worth against others. Social media fuels this like gasoline on a fire.

Studies show that excessive social media use correlates with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and loneliness. The irony is bitter: platforms designed to connect us can leave us feeling more alone.

Teenagers are especially vulnerable. Rates of depression and self-harm have soared since the advent of smartphones. Girls, in particular, suffer under the weight of beauty filters, likes, and the brutal economy of online popularity.

Children of the Algorithm

Perhaps the most sobering consequences of tech addiction emerge in children. In homes around the world, toddlers swipe iPads before they can talk. Elementary kids plead for Roblox. Teens vanish into TikTok for hours.

Early exposure to screens is changing the architecture of developing brains. Pediatricians warn of language delays, impaired social skills, and shortened attention spans. A child’s brain, designed to absorb the real world through touch, sight, sound, and human interaction, becomes trapped in a two-dimensional reality.

Jean Twenge, author of iGen, documents how post-millennial youth spend less time with friends, less time dating, less time outside. They report unprecedented levels of loneliness and anxiety. Many sleep with phones under their pillows, waking through the night to check notifications.

Tech executives know the danger. Many Silicon Valley titans strictly limit their own children’s screen time, sending them to “low-tech” schools where pencils and conversation replace screens. It’s a glaring hypocrisy: those who design the addictive apps protect their offspring from their own creations.

Digital Dementia

In South Korea, where broadband speeds are among the fastest in the world, doctors now diagnose young people with “digital dementia.” Patients suffer memory loss, lack of concentration, and cognitive decline. The phenomenon mirrors the cognitive damage seen in head trauma or old age, but it’s driven not by injury or disease—but by screens.

People who rely on GPS for every journey stop building mental maps. Those who let smartphones remember birthdays, phone numbers, and appointments exercise their working memory less often. Like unused muscles, cognitive faculties atrophy.

This is not merely speculation. Brain imaging reveals thinning of gray matter in the anterior cingulate cortex among heavy tech users. That region governs decision-making, empathy, and impulse control.

We are outsourcing our minds, and the cost may be higher than we imagine.

The Pull of the Feed

Consider the story of David, a bright college student who once devoured novels and wrote poetry. In his freshman year, he joined TikTok “just for fun.” A few minutes each night became hours. He stopped reading books, found it hard to sit through lectures, and began to feel anxious if he left his phone in another room.

When he tried to quit, he felt a gnawing restlessness. His fingers twitched, seeking the comfort of the screen. He confessed, “It feels like I’m trying to leave a cult. Like I’ve forgotten how to be bored.”

David’s story is not unique. Around the world, millions experience a compulsion so subtle it often escapes notice. Unlike drugs, tech addiction rarely produces dramatic overdoses. Instead, it erodes life in small increments—stealing time, scattering attention, erasing presence.

The feed calls to us like a siren’s song. Each flick of the thumb promises novelty, delight, outrage. And we follow, deeper into the depths.

The Loneliness of Connection

Paradoxically, the hyper-connected age has ushered in a loneliness epidemic. Studies from the U.S., the U.K., and Japan report rising rates of chronic loneliness, now recognized as a public health crisis.

Humans evolved to read subtle cues in faces and voices. A text message cannot replicate the micro-expressions, the touch of a hand, the scent of another human. Video calls help, but they flatten presence into pixels and bandwidth delays.

Tech gives us connection without intimacy, interaction without presence. We gather likes and followers yet starve for real human warmth.

This loneliness has physiological consequences. Chronic social isolation elevates stress hormones, raises blood pressure, weakens the immune system, and increases mortality risk as much as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. In seeking digital connection, we risk losing the flesh-and-blood bonds that keep us alive.

Hope in the Human Spirit

Despite the shadows, hope flickers.

Neuroscience teaches us that the brain remains plastic well into adulthood. Circuits forged by compulsive tech use can, with time and discipline, be reshaped. We can retrain our minds for stillness, focus, and presence.

Around the world, movements have emerged to reclaim life from the digital tide. Digital detox retreats offer phone-free weekends. Apps exist to block other apps. Authors like Cal Newport champion “digital minimalism,” urging us to rediscover the joys of solitude and deep work.

Mindfulness meditation is gaining popularity as an antidote to digital overload. Studies show it strengthens the prefrontal cortex, dampens anxiety, and improves attention span. By training the mind to observe impulses without obeying them, we can regain sovereignty over our attention.

Parents are learning to set screen limits, to model device-free time, to ensure children experience real play. Educators are experimenting with tech-free classrooms where curiosity blooms without digital crutches.

Yet the challenge remains immense. We are creatures of habit. The same algorithms that trap us are exquisitely skilled at pulling us back. Resisting tech addiction is not merely an individual battle—it may demand societal changes, regulation, and a reimagining of how we value human attention.

Reclaiming the Present Moment

Standing at the crossroads, we face a stark choice. Will we allow ourselves to become mere extensions of machines, our brains colonized by infinite scrolls and notification dings? Or can we build a future where technology serves humanity, not the other way around?

In a café, a young woman sets down her phone. She sips her coffee and looks around. The room is alive with voices, laughter, light glancing off glass. For a moment, she feels the pulse of the real world—the warmth of existence beyond the glowing screen.

It’s a small rebellion. Yet in these moments lies salvation.

The story of tech addiction is not yet finished. The pages ahead remain unwritten. The same human ingenuity that forged smartphones can forge paths to freedom. But we must choose wisely.

Because in the end, the greatest app is life itself. And the truest connection begins the moment we look up from our screens.