Pregnancy is often described as a miracle—a time of joy, anticipation, and transformation. But beneath the glow of expectation lies a complex biological process, one that challenges every system in the body. The heart beats faster, blood volume increases, hormones shift dramatically, and the body works around the clock to nurture a growing life. Amid all of this change, sometimes the delicate balance of blood sugar is disrupted. This condition is known as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and it is one of the most common complications of pregnancy worldwide.

Gestational diabetes does not define a woman’s pregnancy, but it does add another layer to her journey. It asks for awareness, discipline, and support, while offering an opportunity to protect both mother and baby from potential complications. Understanding what gestational diabetes is, how it is screened, how diet plays a role, and why postpartum follow-up is critical can empower women and families to face it with strength and knowledge rather than fear.

What is Gestational Diabetes?

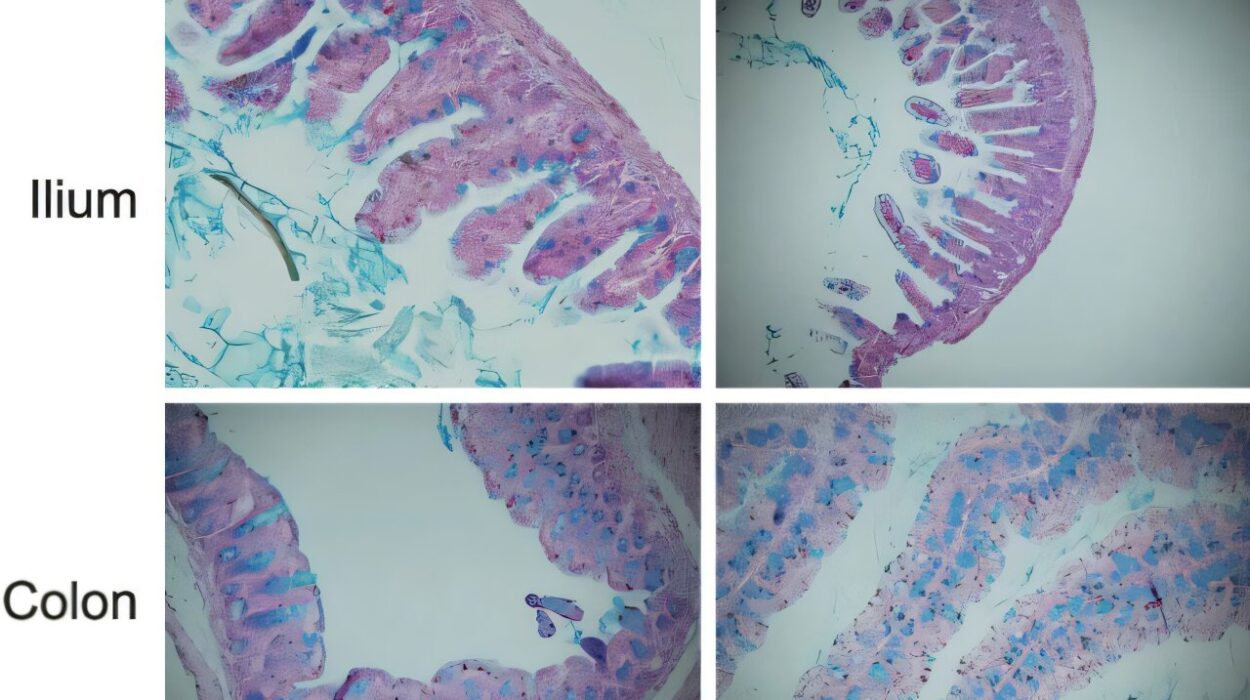

Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes diagnosed for the first time during pregnancy. Unlike type 1 diabetes, which is caused by the immune system attacking insulin-producing cells, or type 2 diabetes, which involves long-term insulin resistance, gestational diabetes arises because pregnancy itself changes how the body processes glucose.

During pregnancy, the placenta produces hormones—such as human placental lactogen, progesterone, and cortisol—that help the baby grow but also make the mother’s body less sensitive to insulin. Insulin is the hormone responsible for moving glucose (sugar) from the blood into the body’s cells for energy. When insulin resistance increases beyond the body’s ability to compensate, blood sugar levels rise, leading to gestational diabetes.

For many women, gestational diabetes causes no obvious symptoms. It may remain hidden, detectable only through routine screening. Yet it can affect both mother and baby in significant ways if unmanaged, increasing the risks of complications such as preeclampsia, premature birth, cesarean delivery, and, for the baby, high birth weight, low blood sugar after birth, or later development of type 2 diabetes.

Gestational diabetes is not rare—it affects up to 10% of pregnancies globally, with variations depending on population and risk factors. Importantly, it is not a result of personal failure or poor health. It is, in many ways, a reflection of the complex demands of pregnancy.

The Importance of Screening

Because gestational diabetes can be silent, screening is essential. Most women undergo glucose testing between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy, though those with higher risk factors—such as obesity, a history of GDM, family history of diabetes, or polycystic ovary syndrome—may be screened earlier.

The most common screening methods include:

- Glucose Challenge Test (GCT): A woman drinks a sweet glucose solution, and blood sugar is measured one hour later. If the result is above a certain threshold, further testing is needed.

- Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT): After fasting, the woman’s blood sugar is tested, followed by measurements one and two (sometimes three) hours after drinking a glucose-rich beverage. This is the definitive diagnostic test.

Screening is more than a medical formality—it is a way of safeguarding two lives at once. Identifying gestational diabetes early allows mothers and healthcare providers to put strategies in place that minimize risks. For women, it can mean fewer complications during delivery. For babies, it can mean healthier growth and development.

The Emotional Landscape of Diagnosis

Receiving a diagnosis of gestational diabetes can be overwhelming. Many women feel fear, guilt, or confusion. Thoughts like “Did I cause this?” or “Am I failing my baby?” are common, but they are misplaced. Gestational diabetes is not a reflection of negligence—it is the result of hormonal and metabolic changes that no mother can control.

Acknowledging these emotions is as important as managing blood sugar. A strong support system—partners, family, friends, healthcare providers—can make the difference between a diagnosis feeling like a burden and feeling like a manageable challenge. Understanding that gestational diabetes is both temporary and treatable helps shift the perspective from fear to empowerment.

The Role of Diet in Managing Gestational Diabetes

Diet is the cornerstone of managing gestational diabetes. While some women may need medication or insulin, the majority can maintain healthy blood sugar levels with nutritional changes and mindful eating. Diet becomes not just a way to fuel the mother, but also a tool to protect the baby.

The goals of dietary management are threefold:

- To maintain blood sugar within target ranges.

- To support healthy weight gain during pregnancy.

- To provide all the nutrients needed for both mother and baby.

Balanced Eating for Blood Sugar Control

Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of glucose, so managing the type, timing, and portion of carbohydrates is key. This does not mean eliminating carbs, but choosing them wisely:

- Whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits provide fiber that slows glucose absorption.

- Simple sugars, refined flours, and sugary beverages can cause spikes in blood sugar and are best limited.

- Pairing carbohydrates with protein or healthy fats helps stabilize blood sugar levels.

Eating smaller, more frequent meals rather than three large ones can also help. For example, a woman might eat three moderate meals and two to three snacks across the day. Breakfast may include whole-grain toast, eggs, and avocado; lunch could be a salad with grilled chicken and quinoa; snacks might feature nuts, yogurt, or apple slices with peanut butter.

Cultural and Personal Flexibility

Dietary advice should never be one-size-fits-all. Food is deeply cultural and personal, and expecting women to suddenly abandon their traditional diets can be unrealistic and disheartening. Instead, healthcare providers and dietitians can work with women to adapt cultural staples into healthier patterns. For instance, in South Asian diets, rice can be replaced with smaller portions of brown rice or combined with lentils and vegetables to balance the glycemic load.

The Power of Mindful Eating

Gestational diabetes offers an opportunity for mindfulness around food. Instead of focusing on restrictions, women can view it as a way to nourish themselves and their baby with intention. Each bite becomes part of a shared journey toward health. In this light, diet is not a punishment but an act of care and love.

Exercise as a Partner to Diet

Though diet is central, physical activity is equally important in managing gestational diabetes. Exercise makes the body more sensitive to insulin and helps lower blood sugar levels. Gentle, regular movement—such as walking, swimming, or prenatal yoga—can make a significant difference.

Of course, exercise during pregnancy should always be discussed with a healthcare provider, especially if there are complications or risks. But in most cases, 20–30 minutes of moderate activity most days of the week can improve glucose control, boost energy, and even ease common pregnancy discomforts like back pain or swelling.

Medical Management When Needed

For some women, diet and exercise may not be enough to control blood sugar. In such cases, medication becomes necessary. Insulin is the most common treatment, as it does not cross the placenta and is considered safe for the baby. Some oral medications may also be used under medical supervision.

The goal of medical management is not to “punish” a mother for not controlling her blood sugar with lifestyle changes. Instead, it is an acknowledgment that every body responds differently to pregnancy’s hormonal demands. Medication is simply another tool to ensure both mother and baby remain safe.

Monitoring Blood Sugar

Self-monitoring of blood glucose is often recommended for women with gestational diabetes. Using a small device called a glucometer, women can check their blood sugar several times a day—usually fasting in the morning and after meals. These readings provide real-time feedback and help guide dietary and medical adjustments.

While frequent testing can feel burdensome, many women describe it as empowering, giving them direct insight into how their choices and bodies interact. It transforms management from guesswork into informed action.

Risks and Complications Without Management

When gestational diabetes is left untreated, risks rise for both mother and baby. Babies may grow larger than average (macrosomia), making vaginal delivery difficult and increasing the likelihood of cesarean section. After birth, babies may experience low blood sugar (neonatal hypoglycemia) because their insulin production remains high even after the maternal glucose supply is cut.

For mothers, unmanaged gestational diabetes increases the risk of high blood pressure, preeclampsia, and future development of type 2 diabetes. These outcomes underline why screening, diet, and monitoring are not merely recommendations—they are lifelines for both mother and child.

The Postpartum Chapter: Why Follow-Up Matters

One of the most overlooked aspects of gestational diabetes is what happens after delivery. In many cases, blood sugar levels return to normal once the placenta is delivered. The hormones that caused insulin resistance are gone, and the body resets. For many women, this feels like the end of the story.

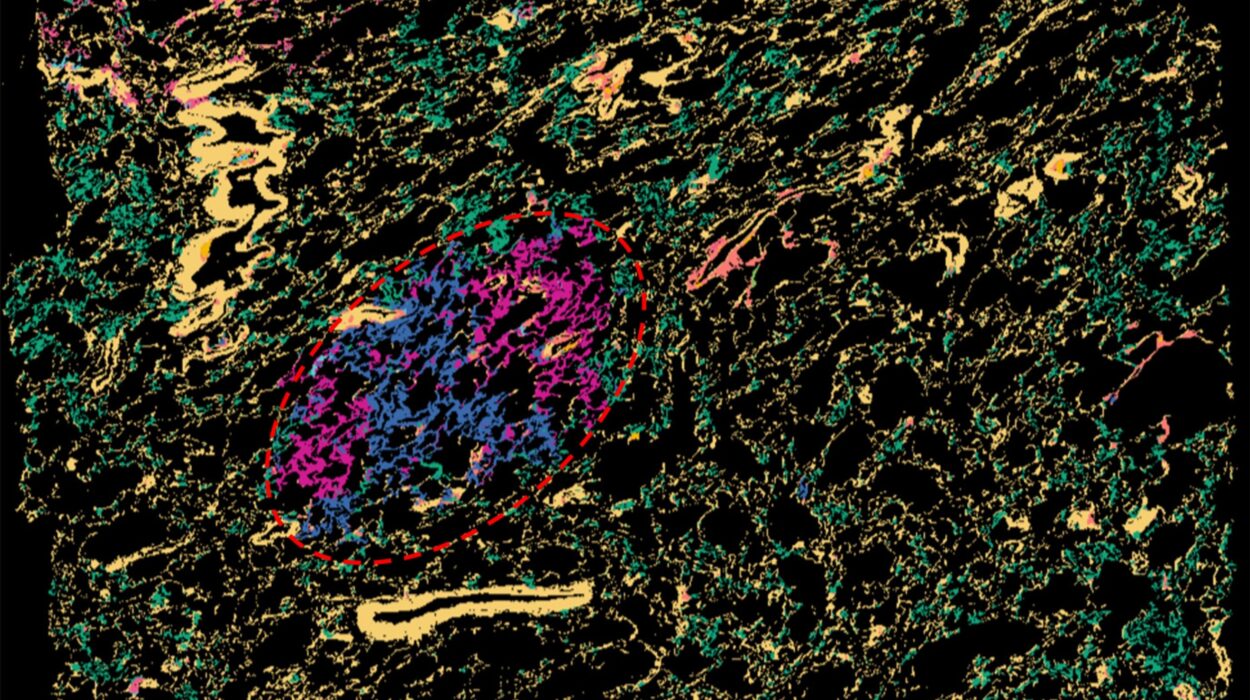

But gestational diabetes carries a shadow into the future. Women who have experienced GDM face a seven-fold higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life. Additionally, children born to mothers with GDM may also carry an increased risk of obesity and diabetes as they grow.

This is why postpartum follow-up is crucial. Healthcare providers usually recommend a glucose tolerance test 6–12 weeks after delivery to confirm whether blood sugar has returned to normal. Beyond that, women should continue to have regular screening every 1–3 years.

Postpartum follow-up is not just about preventing diabetes—it is about long-term health. Lifestyle adjustments such as balanced eating, maintaining a healthy weight, and staying active can significantly reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. For women who have already navigated gestational diabetes, these habits are not unfamiliar; they are simply carried into the next chapter of life.

Breastfeeding and Gestational Diabetes

Breastfeeding offers unique benefits for mothers with a history of gestational diabetes. It helps the mother’s body use insulin more effectively, lowers her risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and contributes to postpartum weight management. For babies, breastfeeding provides optimal nutrition and may reduce their risk of obesity and metabolic disorders later in life.

Breastfeeding is not always easy—many women face challenges with supply, latch, or fatigue—but with support and guidance, it can become a powerful part of postpartum care.

The Broader Picture: Public Health and Awareness

Gestational diabetes is not only a personal challenge but also a public health issue. As rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes rise globally, so do rates of GDM. This places strain on healthcare systems, especially in countries where access to prenatal care is limited.

Raising awareness about gestational diabetes—its risks, screening, and management—is essential. Community health programs, culturally sensitive dietary guidance, and accessible postpartum follow-up can transform outcomes for millions of women and children. In this way, addressing GDM is not only about individual pregnancies but also about breaking intergenerational cycles of diabetes.

The Human Story Behind the Science

Every statistic about gestational diabetes hides a human story: the woman who pricks her finger daily to monitor blood sugar; the mother who adjusts her traditional recipes to protect her baby; the family who rallies around her to provide encouragement and love. These stories are stories of resilience, not defeat.

Gestational diabetes may complicate pregnancy, but it does not define it. Many women with GDM go on to deliver healthy babies and to lead healthy lives themselves. What makes the difference is knowledge, support, and the willingness to embrace both medical guidance and self-care.

Looking Toward the Future

The future of gestational diabetes care is bright with promise. Advances in continuous glucose monitoring, personalized nutrition plans, and genetic research may one day allow for earlier detection, better treatment, and lower risk. Telemedicine is already expanding access to education and monitoring for women in remote areas.

Beyond technology, the future also lies in compassion: in ensuring that no woman feels alone, guilty, or afraid when facing GDM. With proper care, gestational diabetes can be managed safely, and its long-term risks can be mitigated.

Conclusion: Hope in Every Step

Gestational diabetes is a complex, sometimes daunting condition, but it is not insurmountable. Through timely screening, thoughtful dietary choices, appropriate medical care, and diligent postpartum follow-up, women can navigate this journey with confidence.

The heart of the matter is this: gestational diabetes is not a verdict but a call to action. It is a reminder of the resilience of the human body, the power of knowledge, and the profound love that motivates mothers to protect their children. Every step—from the first screening to the last postpartum check-up—is a step of hope, ensuring healthier futures for both mother and baby.