Few creatures capture the imagination quite like the coelacanth. For decades, it was thought to have vanished forever, its last traces buried in rocks over 65 million years old. Then, in 1938, a fisherman off the coast of South Africa hauled up a strange blue fish from the depths of the Indian Ocean. With its lobed fins, ancient anatomy, and ghostly presence, the coelacanth was declared a “living fossil”—a direct link to prehistoric seas that had somehow survived unchanged into the modern age.

Since then, coelacanths have become icons of scientific wonder, living reminders that evolution’s story is always more complex than we think. Yet even as biologists marveled at the survival of these rare deep-water giants, paleontologists faced a puzzle: the fossil record of coelacanths was strangely patchy, with gaps that made it difficult to trace their history.

Now, thanks to the sharp eyes and persistence of a young researcher, part of that missing story has resurfaced—hidden in plain sight for nearly 150 years.

A Student’s Discovery Among Forgotten Bones

The breakthrough began not in the field, but in the quiet halls of museums. Jacob Quinn, while studying for his Master’s in Paleobiology at the University of Bristol, noticed something unusual. Many fossils in collections across the U.K. had been labeled as belonging to Pachystropheus, a small marine reptile from the Triassic Period. But to Quinn’s trained eye, some of those bones looked suspiciously fish-like.

The resemblance was uncanny: elongated bones that could pass for reptile remains, yet carried subtle features of coelacanth anatomy. Where others had seen lizards or mammals, Quinn saw clues to a different story. Determined to test his hunch, he began traveling to museums, examining drawers and display cases filled with fossils that had not been closely studied for more than a century.

What he found was astonishing. The same misidentification had been repeated again and again, stretching back to the late 1800s. Fossils thought to belong to reptiles, and in some cases even mammals, were in fact the remains of coelacanths.

A Hidden Trove of Fossils

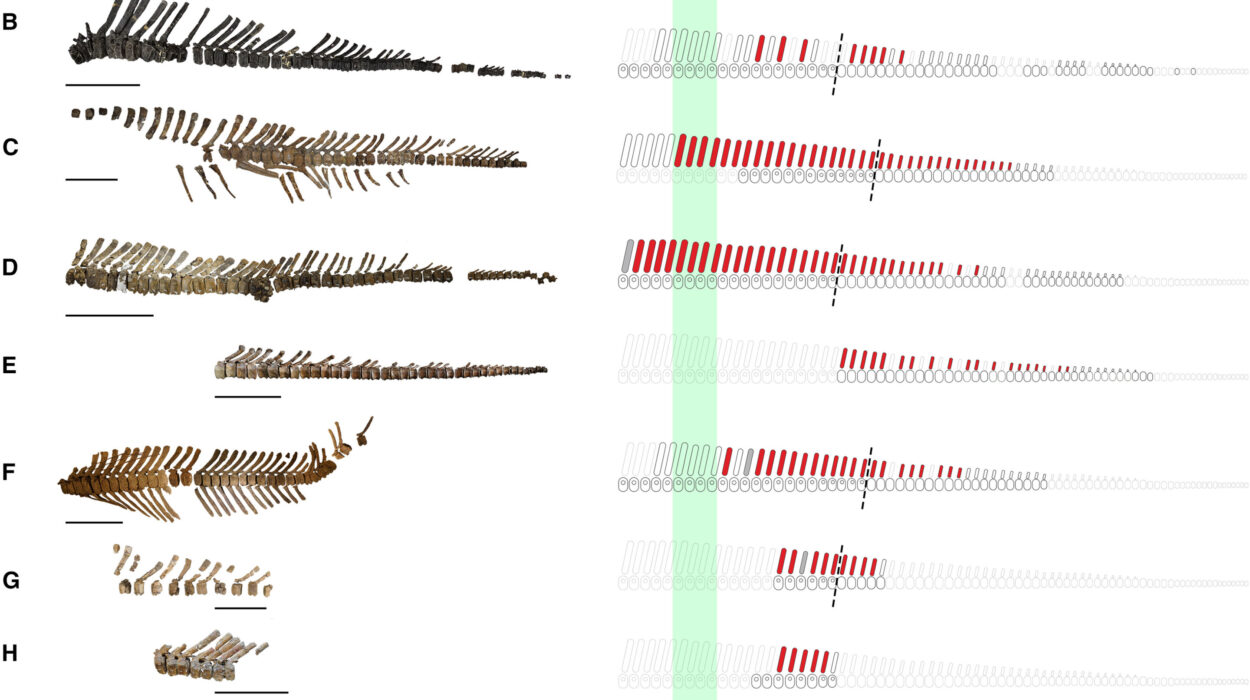

Before Quinn’s study, only four reports of coelacanth fossils had been made from the British Triassic. After his careful re-examination, that number leapt to over fifty. Some of these fossils had been on display for generations, their true identity overlooked. Others were tucked away in storage drawers, quietly waiting for someone to recognize their significance.

Using modern X-ray scans, Quinn was able to confirm his identifications. The fossils belonged mostly to the extinct group known as Mawsoniidae—relatives of today’s coelacanths that once thrived in warm seas. These specimens revealed not only the presence of coelacanths in Britain during the Triassic but also hinted at a diverse and thriving community of them. Some individuals grew to more than a meter in length, evidence of a rich ecosystem that had gone unrecognized for decades.

Life in a Triassic Archipelago

To imagine these fish in their prime, one must picture Britain 200 million years ago. The landscape was unrecognizable, not the cool, green island we know today but a tropical archipelago of small islands scattered across shallow seas. Warm waters lapped against the shores of the Mendip Hills and Bristol Basin, creating an environment teeming with marine reptiles, fish, and invertebrates.

In this ancient seascape, coelacanths lurked as opportunistic predators. Much like their modern descendants in the depths of the Indian Ocean, they likely hovered near the seabed, waiting for unsuspecting prey. Their diet probably included smaller fish, crustaceans, and—ironically—the very Pachystropheus reptiles their fossils were once mistaken for.

The rediscovered fossils suggest that these ancient coelacanths were not rare oddities but important members of the ecosystem, filling a role similar to that of ambush predators today.

The Long Silence of Forgotten Specimens

One of the most remarkable aspects of this discovery is not just what was found, but where it was found. Many of these fossils had been housed in museums since the Victorian era, sometimes displayed under the wrong name, sometimes left in storage with vague labels. Generations of visitors and scientists had passed by them without realizing their significance.

This is a humbling reminder of how science progresses—not always with new excavations, but often with fresh eyes revisiting what was thought to be understood. Fossils do not change, but interpretations do. A specimen dismissed as unimportant in the 19th century can, with modern tools and insight, rewrite an entire chapter of evolutionary history.

Coelacanths and the Mystery of Survival

The rediscovery of these fossils does more than fill a gap in the record—it deepens the mystery of the coelacanth itself. Why did this lineage, which flourished in ancient seas, manage to survive when so many others perished? What qualities allowed it to persist through mass extinctions, climatic shifts, and continental drifts?

The answers may lie in their biology. Coelacanths have a slow, energy-efficient metabolism, lobed fins that allow for flexible movement, and a deep-water lifestyle that may have shielded them from environmental upheavals. Yet their fossil history reveals they were once far more widespread and ecologically diverse than their modern representatives.

By studying both the living species and their fossil relatives, scientists can begin to piece together a fuller picture of how resilience is built into the evolutionary process.

A Future of Rediscovery

Quinn’s work highlights a truth often overlooked in paleontology: some of the greatest discoveries are not buried underground but hidden in plain sight, waiting in museum collections. Every fossil has a story, but sometimes it takes the right perspective—and the right technology—to hear it.

For the coelacanth, these rediscovered bones do more than add to its fossil record. They reconnect us to a time when Britain’s seas teemed with strange life, when predators with lobed fins haunted tropical waters, and when the ancestors of living fossils swam among creatures long vanished.

The story of the coelacanth is a story of survival against all odds, but also of rediscovery—a reminder that history is never fully written, and that even in the drawers of old museums, the past is still speaking to us.

More information: Jacob G. Quinn et al, Coelacanthiform fishes of the British Rhaetian, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2025.2520921