At first glance, virtual reality seems like something plucked from science fiction: slip on a headset and you’re no longer here, but somewhere else entirely. A medieval battlefield. A Martian landscape. A virtual concert pulsing with light and sound. What began as a dream of tech enthusiasts and futurists is now a tangible part of modern experience. But beneath the surface of glowing screens and motion controllers lies something far deeper and far more profound: the human mind’s extraordinary ability to believe.

Virtual reality, or VR, is not just about what we see. It’s about what we feel—emotionally and sensorily—and how our brain accepts artificial inputs as real. It’s about immersion. And to truly understand VR, you must understand why, when the simulation is right, your heart races at a virtual cliff’s edge or your hands sweat in a fabricated firefight.

This article aims to take you beneath the plastic casing and pixelated surface of VR and explore the science of immersion: how it works, why it’s powerful, and what it reveals about our very perception of reality.

The Brain’s Theater: Perception and Plausibility

To demystify VR, you must first look inward. The human brain is an astonishing organ—not because it always gets things right, but because it’s constantly making educated guesses. What we call “reality” is a construction, built from partial information. The eyes take in light, the ears receive vibration, the skin senses temperature and texture—but the brain interprets.

That interpretation is what VR hacks into.

Imagine you’re standing on the edge of a virtual skyscraper. You know, logically, that you’re in your living room. But if the visual cues, spatial audio, and even subtle haptic feedback align just right, your body will respond as if the danger is real. Your muscles tense. Your balance shifts. Your breath catches.

This is the magic of immersion—not deception, but plausibility. A virtual world doesn’t need to look photorealistic to be immersive; it needs to feel coherent. If your brain accepts the sensory input as consistent and the environment responds to your actions in believable ways, it surrenders. It believes.

Stepping Through the Frame: The Role of Presence

At the heart of VR immersion is a psychological concept known as presence. Presence is the feeling of “being there” inside a virtual environment. It’s what makes the difference between watching a 3D movie and being in a VR game. Presence is not automatic. It’s earned through carefully orchestrated illusions.

Researchers have identified several dimensions of presence—spatial, social, and self. Spatial presence is the sense that you’re physically located in the virtual space. Social presence is the belief that other characters or avatars in the space are aware of you and responsive. Self-presence refers to your sense of having a body inside the environment that belongs to you.

Each layer contributes to the whole. For example, if you reach out and your virtual hand responds with just the right delay and motion, your brain begins to adopt it as your own. If another avatar looks at you when you speak, nods in agreement, or steps back when you move too close, your social instincts kick in. These experiences stitch together a sense of immersion more powerful than any single image or sound.

Beyond the Screen: The Hardware Behind the Illusion

To create the illusion of presence, VR technology relies on a symphony of hardware working in harmony. The headset, of course, is the gateway—a compact device that positions two screens just inches from your eyes, each showing a slightly different image to simulate stereoscopic depth. High-resolution displays, refresh rates of 90Hz or higher, and wide fields of view are essential to creating a convincing visual world.

But vision alone isn’t enough. Motion tracking is the bridge between your physical body and your virtual self. Head-tracking systems use gyroscopes, accelerometers, and infrared sensors to monitor where you’re looking and how you’re moving. Hand controllers, gloves, and even full-body suits allow your gestures and actions to translate directly into the virtual space.

Audio, too, plays a critical role. Binaural spatial sound simulates how your ears perceive direction and distance in the real world. Footsteps behind you. A whisper to your left. A sudden roar overhead. These are not just sound effects—they are anchoring elements that reinforce presence.

New technologies are also emerging: haptic feedback systems simulate touch; treadmills and motion rigs allow walking and running; eye-tracking adds realism by allowing the environment to respond to what you focus on. The result is a growing toolbox for creating increasingly immersive experiences.

The Psychology of Immersion: Why We Buy the Illusion

Why does our brain accept these illusions so readily? The answer lies in cognitive psychology and evolutionary biology. Human perception evolved to be fast, efficient, and context-sensitive, not perfectly accurate. When the brain receives congruent sensory input—when what you see, hear, and feel aligns—it assumes the experience is real, or at least real enough.

This flexibility of mind is what makes VR both powerful and potentially transformative. Our sense of reality is deeply tied to the body and environment. When those are manipulated—even virtually—the mind can be tricked, but also retrained.

In VR, researchers have studied everything from the rubber hand illusion (in which people come to feel a fake hand as their own) to virtual body swapping (which can temporarily alter perceptions of race, gender, or age). These studies reveal not just how we experience the virtual, but how fluid our sense of self really is.

VR is a mirror that shows how easily our minds can be shaped—and sometimes reshaped for good.

Gaming and Beyond: Where Immersion Meets Purpose

While VR’s most visible playground is gaming—epic sword fights, alien landscapes, digital dance floors—it’s far from limited to entertainment. Immersion has become a tool for everything from education to therapy.

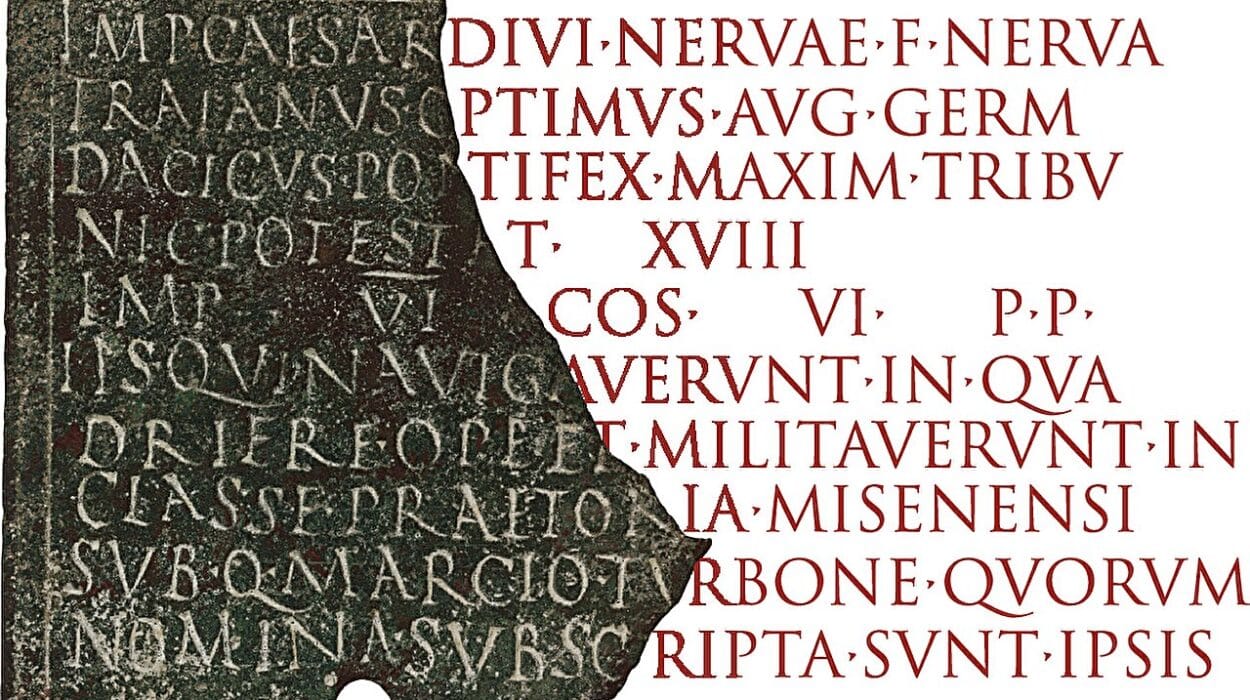

In classrooms, VR enables students to walk through Roman ruins, explore molecular biology at scale, or visit the International Space Station. The sense of presence fosters engagement far beyond textbooks or videos. It’s not just learning—it’s experiencing knowledge.

In healthcare, immersive VR is being used for pain management, exposure therapy for phobias, and rehabilitation after strokes. A burn patient playing an icy VR game called SnowWorld can experience less pain during treatment. A veteran reliving a controlled virtual battlefield can gradually heal trauma. The brain, it turns out, can be soothed and reshaped by carefully crafted realities.

Architecture, design, and engineering all use VR to prototype and explore ideas before physical construction. In art, creators are pushing boundaries of what a canvas can be when the viewer is inside the painting.

The applications are as limitless as imagination—because the medium is not bound by the physical world.

Motion Sickness and the Limits of the Senses

Yet, for all its wonder, immersion is fragile. VR sickness—or cybersickness—is a real and limiting issue. It occurs when there’s a mismatch between what the eyes see and what the body feels. Your headset tells your brain you’re moving, but your inner ear knows you’re standing still. The result: nausea, dizziness, and disorientation.

Researchers and developers have tackled this with better tracking, shorter session designs, and new locomotion methods like teleportation. But it’s a reminder that the brain has limits—and that immersion must work in harmony with biology, not against it.

Just as importantly, emotional overload is a growing concern. In powerful VR simulations, emotional realism can be intense. The boundary between real trauma and virtual exposure can blur. Ethical considerations are beginning to emerge: what should be simulated? What should remain off-limits? These questions are not technical—they are human.

The Neuroscience of Real and Virtual

One of the most fascinating aspects of VR immersion is its window into the brain. Neuroscientists studying brain activity during VR sessions have found surprising overlaps between virtual and real experiences.

When a person in VR sees their virtual arm being touched, the somatosensory cortex—the region responsible for processing touch—is activated as if the real arm were touched. When navigating a virtual maze, the hippocampus engages just as it would in a physical space.

Even more striking is the plasticity shown during long-term VR use. Studies suggest that immersive VR therapy can rewire neural pathways—potentially helping those with PTSD, phobias, or physical impairments. It’s not just about fooling the brain temporarily; it’s about teaching it new ways to perceive and respond.

As neuroscience continues to map the brain’s response to immersion, we are beginning to grasp just how deep the rabbit hole goes. Virtual experiences can become encoded as memories, impact behavior, and shift emotional responses. The boundary between virtual and real, in neurological terms, is becoming less distinct.

Philosophical Echoes: What Is Reality, Anyway?

The rise of VR has also sparked profound philosophical questions. If a virtual experience can provoke real emotion, if it can trigger genuine memory, can it be considered real?

This is not a new debate. Plato’s cave allegory warned of mistaking shadows for truth. Philosophers from Descartes to Baudrillard have questioned the reliability of perception. VR puts those theories into practice—allowing us to live the illusion and then wake up from it.

But perhaps the lesson is not about distrust, but about flexibility. Reality is not always a fixed external truth. It is also a felt experience. VR reveals just how participatory our understanding of the world is—how much we build it from the inside out.

In doing so, it challenges us to reconsider not just what is real, but what is meaningful.

The Future of Immersion: A Second Skin for the Mind

As technology advances, VR immersion is moving toward something even more seamless. Headsets are shrinking. Foveated rendering and eye-tracking reduce computing strain while improving realism. Full-body haptics and brain-computer interfaces are no longer fiction.

Soon, VR may feel less like entering a simulation and more like inhabiting a second skin—a digital body with new rules, new freedoms, and new responsibilities.

Mixed reality (MR) and augmented reality (AR) are blending the real and virtual worlds even further. Instead of disappearing into a headset, you may one day interact with virtual content layered over your kitchen table, your classroom, your city street. The boundaries between “there” and “here” are dissolving.

As immersion deepens, society must grapple with its implications. Will VR become an escape or an evolution? A distraction or a new dimension of truth? The answers will shape how we live, learn, connect, and dream.

The Power and Responsibility of Building Worlds

In the end, immersion is not just a technical achievement—it is a moral one. Those who design virtual worlds hold immense power. They shape perception, influence behavior, and mold memory. With that power comes responsibility.

What stories will we tell in these worlds? What truths will we illuminate—or obscure? Will we create spaces that uplift, educate, and heal? Or will we retreat into fantasy, insulated from the struggles of the real world?

Virtual reality is a mirror, yes—but it is also a brush. A chisel. A pen. It is a medium through which the human spirit can express itself anew.

To demystify VR is not to diminish its magic. It is to appreciate the astonishing blend of neuroscience, art, engineering, and empathy that makes it possible.

Immersion is not about escape. It is about connection—to ideas, to others, and ultimately, to the boundless flexibility of the human mind.