Dinosaurs have never truly left us. Though their bones rest in ancient stone and their mighty roars are silent in the fossil record, they live on in our imaginations. From childhood toys to blockbuster films, dinosaurs are symbols of mystery, power, and the forgotten chapters of Earth’s history. They ruled the planet for over 165 million years, yet vanished in what seems like an instant, leaving us with nothing but fossils, footprints, and questions.

And so the thought arises: what if we could bring them back? What if science could resurrect creatures that vanished sixty-six million years ago? Could humanity witness a living Tyrannosaurus rex, see a Triceratops grazing, or watch a Brachiosaurus stretch its neck to the trees?

This idea—so thrilling and terrifying—lies at the crossroads of fantasy and science. Fiction has made it vivid, but science now edges closer to the possibility of de-extinction. The question is no longer just could we, but also should we.

The Science Behind the Dream

To imagine dinosaurs walking the Earth again, we must understand the biological foundation of resurrection. Every organism is built from genetic code, a sequence of DNA that stores instructions for growth, behavior, and reproduction. If that code can be recovered and restored, life could, in theory, be recreated.

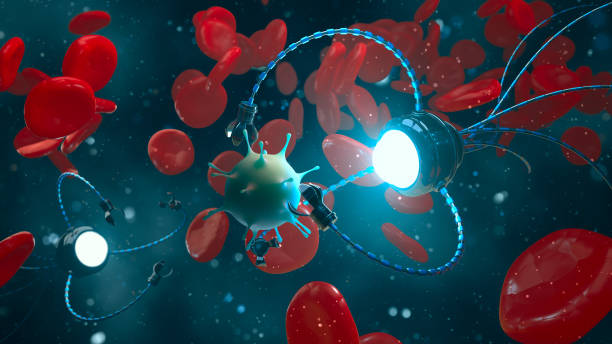

This principle lies at the heart of de-extinction science. For more recently vanished species, such as the woolly mammoth, genetic material has been recovered from frozen remains, allowing scientists to reconstruct parts of their genome. With advanced tools like CRISPR gene-editing, fragments of ancient DNA can be inserted into the genomes of living relatives, creating hybrids that carry traits of their long-lost ancestors.

But dinosaurs present a far greater challenge. Unlike mammoths preserved in ice, dinosaurs left no frozen tissue. Their DNA, over millions of years, has broken down beyond recognition. Even in the best fossils, DNA molecules are too degraded to be read. The dream of pulling dinosaur DNA from ancient amber, as made famous by fiction, is biologically impossible.

Yet science is resourceful. If direct DNA is gone, perhaps there are other paths.

The Challenges of Dinosaur DNA

DNA is a fragile molecule. Heat, moisture, radiation, and time all conspire to break it down. Current studies suggest that DNA has a half-life of about 521 years, meaning that after a few million years, virtually nothing remains. Dinosaurs, having gone extinct tens of millions of years ago, are far beyond that threshold.

This leaves scientists with fragments at best, scattered and incomplete. Imagine trying to rebuild an entire book when only a handful of random letters remain—that is the challenge of dinosaur genetics.

Without intact DNA, cloning a dinosaur in the traditional sense is impossible. The science that might work for mammoths or dodos cannot be directly applied to dinosaurs. But impossibility in one method does not mean impossibility in all.

Birds: The Living Dinosaurs

The most fascinating twist in this story is that dinosaurs are not entirely gone. Their descendants still walk among us—birds. From the smallest hummingbird to the mighty ostrich, modern birds are the direct evolutionary heirs of theropod dinosaurs. They carry within their genomes echoes of the past.

This connection opens new doors. If birds share ancestry with dinosaurs, could their DNA hold hidden remnants of traits long vanished? Could scientists “reverse-engineer” a bird, dialing back evolutionary changes, to resurrect traits like teeth, long tails, or clawed hands?

Experiments already hint at this possibility. Scientists have manipulated chicken embryos to develop snouts resembling those of ancient reptiles. Others have studied dormant genes that, when reactivated, could produce features like teeth. While these results are far from creating a living Velociraptor, they suggest that evolution leaves behind footprints in the genome—footprints that science may someday follow back into deep time.

This approach, sometimes called “reverse evolution,” may not bring back a perfect dinosaur, but it could create an organism resembling one—a “chickenosaurus,” a modern creature carrying echoes of its prehistoric ancestors.

De-Extinction: Lessons from Other Species

To understand whether dinosaurs could return, we must also look at efforts to revive more recent species. The woolly mammoth is perhaps the most famous candidate for de-extinction. With frozen remains preserved in Siberian permafrost, scientists have been able to sequence nearly its entire genome. By splicing mammoth genes into Asian elephants, researchers hope to create a hybrid that resembles the mammoth in appearance and behavior.

The passenger pigeon, once abundant but extinct since 1914, is another target. Using fragments of preserved DNA, geneticists are attempting to reintroduce traits of the passenger pigeon into modern pigeons, with the hope of restoring flocks to North America.

These projects are ongoing, filled with promise and controversy. But they highlight a critical truth: even when DNA is relatively young, de-extinction is enormously difficult. If reviving animals extinct for centuries is challenging, reviving dinosaurs extinct for tens of millions of years is a mountain of near impossibility.

Still, the mammoth and pigeon projects demonstrate that science is pushing boundaries once thought unreachable.

The Jurassic Fantasy Versus Reality

Popular imagination, shaped by films and novels, paints a vivid picture of de-extinct dinosaurs: cloned from DNA in amber, grown in laboratories, unleashed into lush parks filled with prehistoric roars. The fantasy is intoxicating, but the reality is far more constrained.

Even if we could recreate a dinosaur-like genome, we would need a living surrogate species capable of carrying the embryo. Birds, though descended from dinosaurs, are far too different in size and physiology to carry something like a T. rex. There is no living animal that could serve as a natural surrogate for such massive creatures.

Artificial womb technology might one day provide a solution, allowing embryos to develop outside of a host. Yet this field is still in its infancy. For now, the gap between dream and reality remains wide.

The Ethical Questions of Resurrection

Suppose, for a moment, that the scientific barriers were overcome. Imagine that a dinosaur could be brought to life. Would we? Should we?

Science is not only about possibility but about responsibility. Dinosaurs evolved in ecosystems vastly different from our modern world. Their climate, vegetation, and prey have long since vanished. To reintroduce them into today’s environment would mean bringing them into a world that cannot support their needs.

Would a resurrected dinosaur live in a cage, reduced to a mere curiosity for human entertainment? Would we create life only to confine it, stripping it of the freedom it once knew?

There are also risks. Dinosaurs, particularly carnivorous ones, could pose dangers to humans and modern ecosystems. Even herbivores, massive and unpredictable, could devastate habitats. De-extinction raises profound questions not just of science but of morality, ecology, and respect for the natural order.

The Scientific Value of De-Extinction

Despite these challenges, the pursuit of de-extinction is not without purpose. Even if true dinosaurs cannot be revived, the techniques developed in these attempts could advance science in other ways. By studying ancient DNA, scientists gain insights into evolution, adaptation, and extinction. By experimenting with gene editing, they refine tools that may one day cure genetic diseases or protect endangered species.

De-extinction is not only about the past—it is about the future. It forces us to reflect on what it means to lose a species, and whether humanity has a duty to restore what has been erased, especially when extinction was caused by human hands.

Could Dinosaurs Ever Truly Return?

The answer, as of now, is both yes and no. The dream of recreating a perfect Tyrannosaurus rex or a real-life Stegosaurus is beyond our current reach, limited by the decay of DNA and the absence of surrogates. That door, for now, remains closed.

But science may bring us something else: creatures inspired by dinosaurs, shaped from the genomes of their living descendants. A chicken with teeth, a bird with claws, or even a reconstructed reptile with features resembling its ancient ancestors—these are possibilities within the horizon of imagination and technology.

Perhaps we will never see the giants of the Mesozoic exactly as they were, but we may witness glimpses, echoes, and reconstructions that remind us of their majesty. In a way, dinosaurs already live among us, in every sparrow, eagle, and penguin. The miracle of their survival is already written in the wings that beat across our skies.

The True Legacy of Dinosaurs

Even if dinosaurs never return, they have already given us a gift greater than spectacle: perspective. They remind us that life is both fragile and resilient, that dominance does not guarantee survival, and that extinction is the ultimate price of failing to adapt.

Dinosaurs ruled the Earth, yet in their absence, mammals and eventually humans rose. Their story is a warning of impermanence and a lesson in humility. To dream of their return is natural, but to protect the life we have now is perhaps the truer calling of science.

Conclusion: The Roar That Echoes Forever

Could science bring dinosaurs back to life? The dream captivates us because it is not just about dinosaurs—it is about our desire to control time, to undo loss, and to bend nature to our will. It is about confronting extinction, the most final of all fates, and daring to ask whether it must be so.

The truth is that science today cannot resurrect the dinosaurs as they were. Their DNA is too broken, their world too far gone. But the pursuit of that dream enriches our knowledge, sharpens our tools, and deepens our awe for the life that surrounds us.

Dinosaurs may never thunder across the Earth again, but their story will forever thunder in our imaginations. And perhaps that is their true resurrection—not in flesh and bone, but in the endless curiosity they inspire, a curiosity that drives science itself.