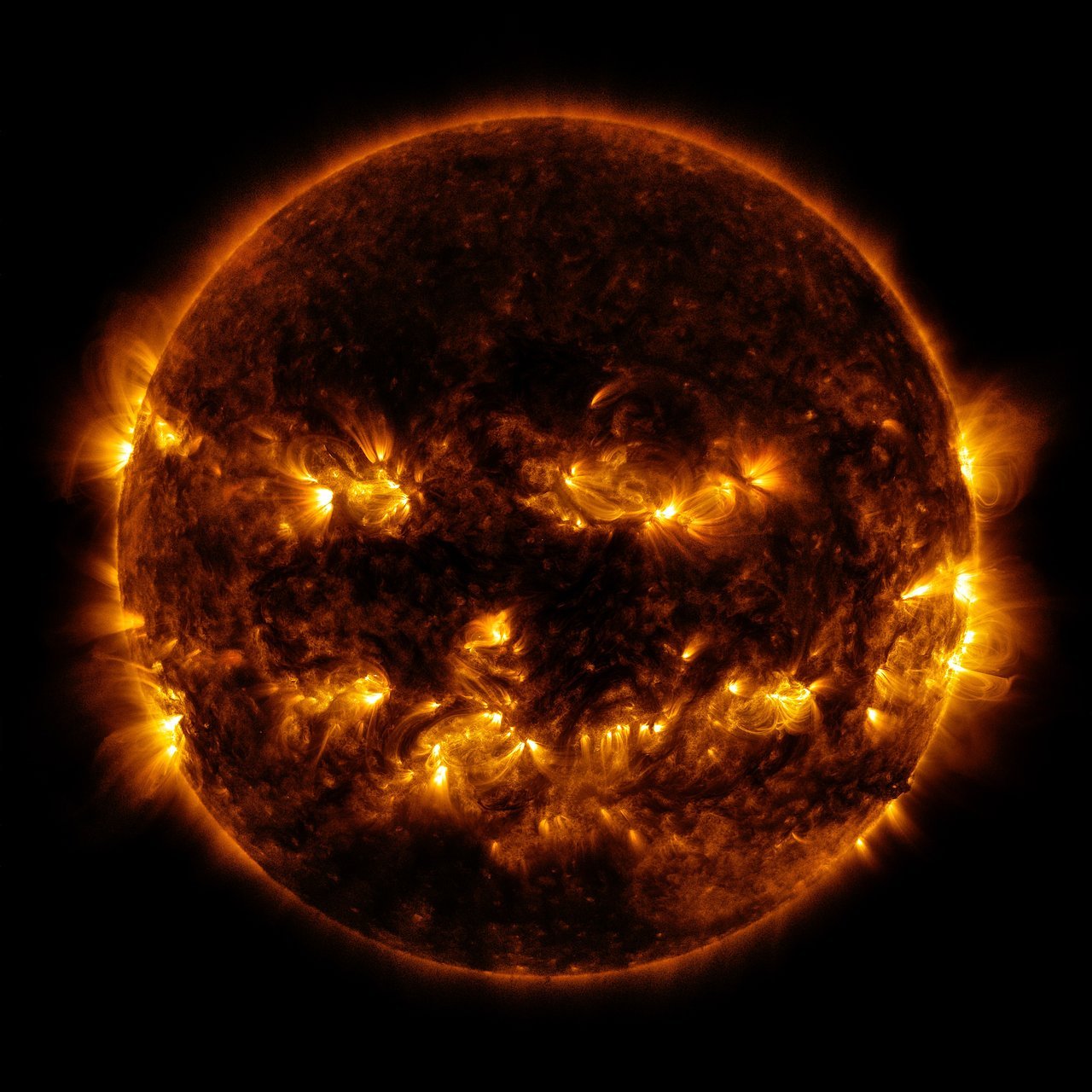

The Sun is not just a glowing orb in the sky—it is the heartbeat of our existence. Every breath of air we take, every bite of food we eat, every drop of water we drink depends on the warmth and energy streaming from our star. It is the silent companion of every dawn, the unseen fuel for every living thing, and the guardian that holds our world in balance. Without it, Earth would be a frozen, lifeless rock adrift in the vast void of space.

Yet the Sun, like all stars, is not eternal. One day—billions of years from now—it will die. And when it does, the fate of humanity will hang in the balance. Could we, fragile beings bound to the rhythms of light and warmth, survive the death of our star? Could we find another home, build new suns, or endure the eternal night?

The answer is not simple. It is a question that reaches into the heart of astrophysics, engineering, biology, and philosophy. It is also a deeply human question, rooted in both fear and hope. For to imagine the death of the Sun is to imagine the death of the familiar world, and to imagine our survival is to imagine the unshakable resilience of the human spirit.

The Life Cycle of the Sun

To understand our chances of survival, we must first understand the fate of the Sun itself. Our star is about 4.6 billion years old—middle-aged by stellar standards. Right now, it burns steadily in its main-sequence phase, fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. But this balance cannot last forever.

In roughly 5 billion years, the Sun’s hydrogen fuel will run low. It will swell into a red giant, expanding so massively that it may swallow Mercury and Venus, and perhaps even Earth itself. The oceans will boil away long before that, the atmosphere will strip into space, and Earth’s surface will become a barren wasteland scorched by relentless heat.

Eventually, the Sun will shed its outer layers in a dazzling display known as a planetary nebula, leaving behind a small, dense remnant: a white dwarf. This faint ember will slowly cool over trillions of years, fading into darkness.

For Earth, this story spells doom. The environment that nurtures life will be annihilated. The question becomes: by then, will humanity—or whatever we have become—be ready to face the end of our Sun?

The Time Before the End

Though the Sun’s final death is billions of years away, the Earth will not remain habitable for nearly that long. In just about a billion years, the Sun will shine about 10% brighter than it does today. That small increase will raise global temperatures enough to evaporate oceans and destabilize the climate. Life as we know it will already be struggling—or gone.

This means humanity, if it is to endure, must act long before the Sun swells into a red giant. Our survival depends not on a last-minute escape, but on a long-term journey into the cosmos.

Escaping a Dying Earth

The first possibility is the most obvious: we leave Earth behind. As daunting as it sounds, this idea is already embedded in our culture. We speak of becoming a multi-planetary species, of colonizing Mars, of building starships to sail between the stars. These dreams may one day become necessities.

Mars offers one possibility for temporary refuge, though it too would ultimately be scorched by the Sun’s red giant phase. The moons of Jupiter and Saturn—Europa, Ganymede, Titan—might provide longer-lasting homes, shielded from the Sun’s increasing brightness. As the Sun grows hotter, the outer solar system will briefly become more habitable. But eventually, even these worlds will be consumed by the dying star’s fury.

Thus, survival requires something even more audacious: leaving the solar system entirely.

Building Arks for the Stars

Interstellar travel is the great barrier between us and survival. The nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, lies 4.37 light-years away—about 25 trillion miles. With today’s fastest spacecraft, the journey would take tens of thousands of years. For humanity to endure, we would need to master technologies far beyond what we possess today.

Ideas already exist in theory. Generation ships—vast, self-sustaining habitats carrying entire communities—could drift between the stars for centuries or millennia. Fusion propulsion, antimatter engines, or even light sails powered by giant lasers could drive such arks forward. In the most daring visions, humans might upload their minds into digital forms and send consciousness itself across the void at near-light speeds.

Each of these paths is speculative, but none is impossible. The physics allows for them, if only our ingenuity, patience, and cooperation can rise to the challenge.

Harnessing New Suns

There is another possibility: instead of fleeing to distant stars, perhaps we could build suns of our own.

Artificial suns—massive fusion reactors sustained on scales far beyond today’s nuclear plants—could provide light and warmth for space habitats. Dyson spheres or Dyson swarms, immense structures that capture the energy of stars, could sustain civilizations for eons. Humanity might not even need a planet at all. Instead, we could live in colossal orbital habitats, free-floating in space, powered by artificial suns and fed by resources mined from asteroids and comets.

This vision transforms survival into something more than endurance. It becomes transcendence—a new stage in human evolution, where life is no longer bound to the fragile crust of a single planet, nor tied to the life cycle of a single star.

Biological and Psychological Challenges

Even if the technology exists, survival is not only about machines and fuel. Humans are biological beings, shaped by millions of years of evolution under Earth’s sky. Could we truly survive in the endless dark of space, far from the comforting presence of the Sun?

Our bodies rely on gravity, on cycles of day and night, on the rhythms of seasons. In artificial environments, we would need to replicate all these conditions. We would need artificial gravity to prevent our bones and muscles from wasting away, artificial light to regulate our circadian rhythms, and sustainable ecosystems to provide food, water, and air.

And then there is the mind. Could generations live in a sealed ship, never feeling the open sky, never seeing a sunrise? Could they endure the psychological burden of exile from the Earth that gave them birth? These questions are as pressing as any engineering challenge. For survival is not only about breathing and eating—it is about finding meaning in the vast silence of the stars.

The Evolution of Humanity

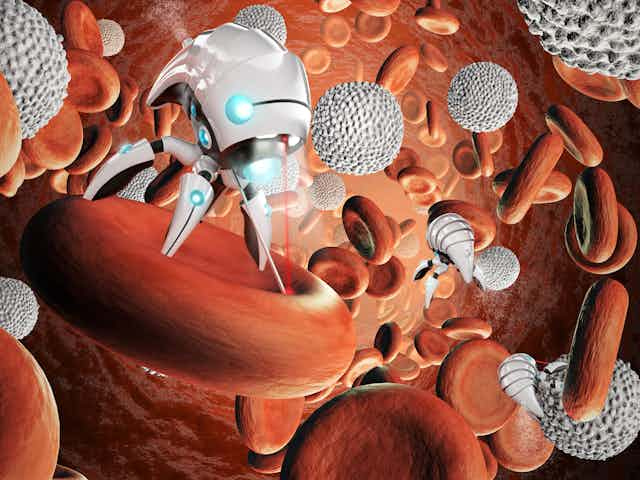

Perhaps the solution lies not in preserving humans as we are, but in changing what it means to be human. By the time the Sun dies, our species may have evolved into something entirely different.

Genetic engineering could allow us to adapt to new environments, making us more resilient to radiation, low gravity, or even the vacuum of space. Cybernetic enhancements could turn us into part-biological, part-machine beings capable of thriving where our ancestors could not. Artificial intelligence may merge with humanity, creating minds that think faster and survive longer than any flesh and blood.

And beyond even this lies the possibility of digital immortality—uploading human consciousness into computers that can travel across the galaxy as streams of information, freed from the limits of biology altogether.

In this sense, the death of the Sun may not be the end of humanity, but the beginning of something new—something that still remembers the warmth of a small yellow star but is no longer bound to it.

The Ethical Dimension

Yet as we dream of survival, we must also ask: should we? Is survival always the highest goal? If humanity endures at the cost of becoming unrecognizable—machine minds adrift in artificial worlds—will we have saved ourselves, or become something else entirely?

These are not scientific questions alone but philosophical ones. Survival at all costs may not be enough. We must also ask what it means to live well, to carry forward not just our genes and technologies but also our values, our creativity, our compassion. To survive the death of the Sun without love, art, and meaning would be a hollow victory.

The Universe as Our Future Home

If we survive, the universe itself becomes our canvas. Other stars, other planets, other galaxies await us. Red dwarfs, which burn far longer than stars like our Sun, could provide stable homes for trillions of years. Black holes, once feared as destroyers, might one day be harnessed as sources of energy. Entire galaxies could become playgrounds for civilizations descended from us.

In this vision, the death of the Sun is not the end of humanity, but the end of childhood. The moment we step away from our first home and take our place among the stars.

The Beauty of the Question

The Sun will die. That is inevitable. Whether we survive is not certain. But perhaps the deeper beauty lies not in the certainty of survival but in the audacity of asking the question.

The fact that we, fragile beings on a small planet, can look ahead billions of years and imagine our fate is itself extraordinary. Science has given us the power to foresee our star’s death. Imagination gives us the power to envision life beyond it.

In the end, the question “Could humans survive the death of the Sun?” is less about prediction than about possibility. It is a mirror reflecting both our fears and our hopes, both our smallness and our greatness.

Conclusion: The Eternal Journey

The Sun will one day fade. Earth will one day be gone. But humanity is not bound to a single star or a single world. Our true home is not Earth, nor even the Sun, but the universe itself.

If we survive, it will be because we dared to dream, to build, to explore, and to believe that the story of life does not end where it began. Perhaps one day, far in the future, our descendants—whether flesh, machine, or something beyond—will look back on the death of the Sun not as an ending but as a milestone.

For the death of our star may mark the birth of our destiny: to carry the light of life into the endless night, to make the universe itself our home, and to prove that even in the face of cosmic darkness, the human spirit can endure.