In the vast tapestry of human history, there are epochs where the stars shine not only in the night sky but also in the intellect of civilizations. The Islamic Golden Age, stretching from the 8th to the 14th century, was such a period—a luminous age when science, philosophy, and the arts flourished under the banners of intellectual freedom, curiosity, and cultural synthesis. Among the many sciences that reached remarkable heights during this time, astronomy held a special place. It was not only a tool of religious devotion and navigation but also a mirror to the universe’s deepest secrets.

Islamic astronomers, standing on the shoulders of Greek, Indian, Persian, and Babylonian predecessors, took the ancient science of the heavens and propelled it into new dimensions. They meticulously observed the skies, refined instruments, built observatories, corrected errors in Ptolemaic models, and laid down the groundwork for what would become the astronomical revolution in Europe centuries later.

Let us journey through this fascinating epoch and discover how Islamic civilization turned its gaze upward—and changed our view of the cosmos forever.

The Spark of Inspiration: Astronomy and Islamic Culture

In Islamic culture, the study of the heavens was more than a scientific pursuit; it was a spiritual and practical necessity. The Quran itself contains numerous references to celestial bodies, calling believers to observe the skies as signs of divine creation. This spiritual encouragement was matched by practical needs. Determining the time for daily prayers, the direction of Mecca (qibla), the start of lunar months for Ramadan and Hajj—these all required astronomical calculations.

Unlike other cultures where religious and scientific authorities often clashed, in the Islamic world, the two coexisted and enriched one another. Scholars who studied the stars were often also theologians, jurists, poets, or philosophers. Astronomy was not merely tolerated—it was funded, celebrated, and institutionalized.

Caliphs and sultans, particularly during the Abbasid era, sponsored scholars and built libraries and observatories. Under their patronage, cities like Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, Cordoba, and Samarkand became radiant centers of knowledge.

The Translation Movement: Breathing New Life into Ancient Knowledge

One of the foundational moments in the Islamic Golden Age was the great Translation Movement centered in Baghdad during the 8th and 9th centuries. Under the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma’mun, the legendary House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) was established. Scholars there translated a vast corpus of Greek, Persian, Indian, and Syriac texts into Arabic. Among these were the astronomical works of Ptolemy, particularly the Almagest, along with Indian treatises such as the Siddhantas and Persian Zij tables.

These texts were not merely translated—they were studied, critiqued, expanded upon, and corrected. Muslim scholars approached inherited knowledge with reverence but not blind acceptance. They questioned inconsistencies, devised alternatives, and in some cases, completely revised the old models.

This intellectual humility and rigor gave rise to a distinctively Islamic school of astronomy that would thrive for centuries.

The Rise of Observatories and Precision Instruments

Unlike earlier astronomers who relied on rudimentary tools or armchair theorizing, Muslim astronomers placed enormous value on observation. They developed and refined instruments that allowed for incredibly precise measurements of celestial positions.

Among the most important instruments was the astrolabe, which Muslim astronomers perfected and used for a multitude of purposes: determining time, locating the qibla, solving trigonometric problems, and observing stars. Other inventions included the armillary sphere, the quadrant, and the sundial.

But even more impressive were the observatories that emerged. One of the earliest major observatories was constructed in Baghdad under Caliph al-Ma’mun around 828 CE. There, astronomers measured the length of the solar year, the tilt of the Earth’s axis, and verified Ptolemy’s star catalog.

Later observatories, such as those in Maragha (Iran), Shiraz, Toledo, and Samarkand, pushed these achievements even further. They employed teams of astronomers and featured large instruments that allowed for observations of unprecedented accuracy—sometimes within seconds of arc.

Pioneers of the Celestial Sciences

The Islamic Golden Age produced a pantheon of brilliant astronomers, many of whom remain largely unknown in the West despite their monumental contributions.

Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850)

Known primarily for founding algebra, Al-Khwarizmi was also a key figure in early Islamic astronomy. He wrote one of the earliest astronomical tables in the Islamic world, drawing from Indian and Persian sources but adapting them for Muslim use. His Zij al-Sindhind helped standardize astronomical practices across the Islamic world.

Al-Farghani (d. c. 861)

Al-Farghani, a court astronomer under the Abbasids, wrote Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions, a summary of Ptolemaic astronomy that became widely read in both the Islamic world and medieval Europe. His measurements of the Earth’s diameter were surprisingly accurate for the time.

Al-Battani (c. 858–929)

Hailing from what is now Syria, Al-Battani refined the Ptolemaic model and produced a new zij based on original observations. He accurately calculated the solar year to within a few minutes and introduced the concept of the solar apogee shifting over time. His work was later cited by Copernicus.

Ibn Yunus (c. 950–1009)

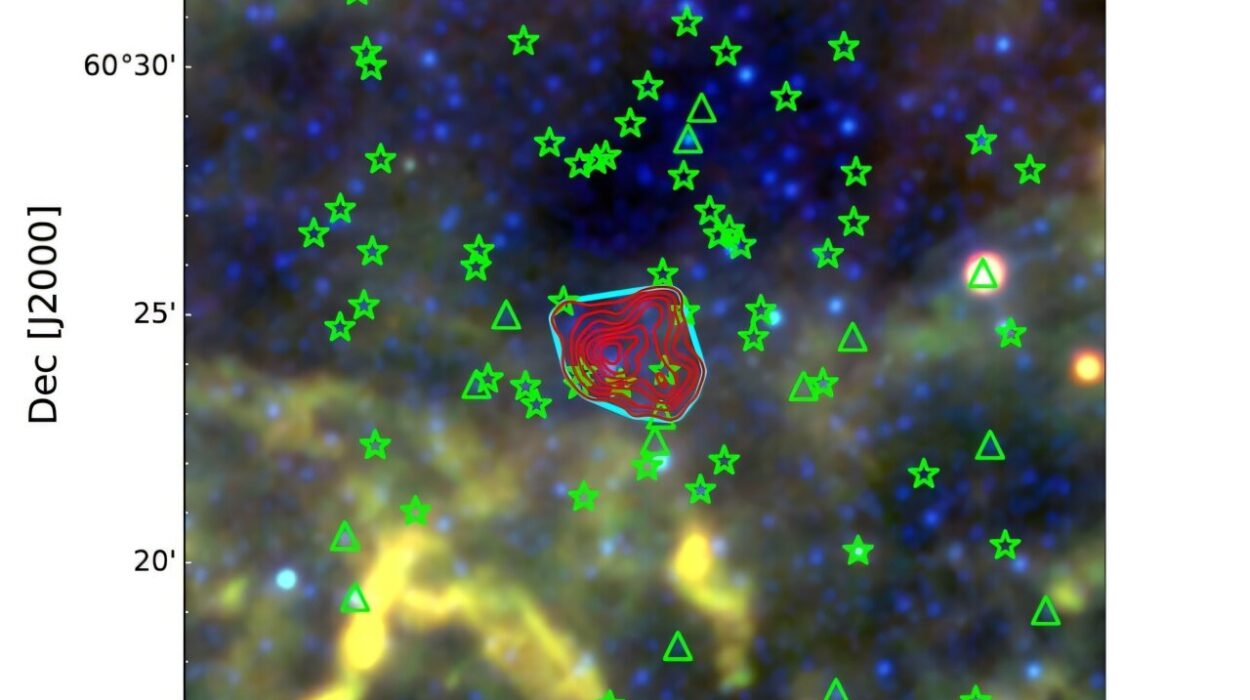

An Egyptian astronomer, Ibn Yunus compiled a zij with over 10,000 observations, including incredibly precise timing of lunar eclipses. His use of trigonometry over geometric models marked a turning point in astronomical methodology.

Al-Zarqali (Arzachel) (1029–1087)

Working in the brilliant intellectual climate of al-Andalus, Al-Zarqali improved the astrolabe and created accurate models of planetary motion. His Toledan Tables became a standard reference in both the Muslim and Christian worlds for centuries.

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274)

A Persian polymath, Tusi directed the Maragha Observatory and devised the Tusi-couple, a geometric model that later influenced Copernicus. He critiqued and revised Ptolemaic models, moving astronomy closer to the heliocentric revolution.

Ulugh Beg (1394–1449)

The Timurid prince and scholar founded the Samarkand Observatory, one of the largest and most advanced in the medieval world. His star catalog contained over 1,000 entries with unprecedented accuracy. Tragically, his scientific pursuits made him enemies in court, and he was assassinated—but his legacy endured.

Innovations in Mathematical Astronomy

The theoretical backbone of Islamic astronomy lay in its mathematics. Astronomers developed spherical trigonometry, essential for understanding celestial motions on a curved sky. They refined sine and tangent tables, often to seven or eight decimal places.

The use of algebra in astronomical calculations—pioneered by Al-Khwarizmi and later enhanced by figures like Omar Khayyam—allowed astronomers to solve complex equations regarding planetary positions, eclipses, and conjunctions.

Perhaps most impressively, Muslim astronomers developed non-Ptolemaic models that attempted to resolve inconsistencies in the geocentric system. While they did not propose a heliocentric cosmos, their critiques of Ptolemy’s epicycles and equants laid critical groundwork for later revolutions.

The Zij: Star Catalogs of Genius

The term zij refers to astronomical handbooks containing tables for calculating the positions of stars, planets, and the sun and moon. They were crucial tools for astronomers, astrologers, navigators, and scholars.

Dozens of zijs were produced across the Islamic world, each building upon and refining its predecessors. These included:

- Zij al-Sindhind by Al-Khwarizmi

- Zij al-Sabi’i by Al-Battani

- Zij al-Hakimi by Ibn Yunus

- Zij-i Ilkhani by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

- Zij-i Sultani by Ulugh Beg

Each zij not only included tables but also elaborate theoretical introductions explaining the models, instruments, and observational methods used.

Celestial Navigation and Timekeeping

Astronomy in the Islamic Golden Age wasn’t limited to theory. It had real-world applications in timekeeping and navigation, crucial for trade, pilgrimage, and daily religious life.

Muslim astronomers and engineers created muwakkits, or timekeepers, who operated in mosques to calculate prayer times. They used sundials, water clocks, and mechanical devices—some of extraordinary complexity.

Navigation across vast deserts and oceans was made safer through celestial knowledge. Mariners used the positions of stars, lunar mansions, and portable astrolabes to orient themselves. The Islamic world’s mastery of the skies helped facilitate the vast trade networks that stretched from Spain to China.

Astronomy and Philosophy: The Celestial Hierarchy

The cosmology of the Islamic Golden Age was often deeply intertwined with philosophy. Many scholars saw the heavens not only as physical phenomena but also as metaphysical realities.

Philosophers like Al-Farabi, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) integrated Aristotelian cosmology with Islamic theology. They envisioned a layered cosmos of concentric spheres, each moved by an intelligence, culminating in the “Prime Mover” or God.

These philosophical views weren’t mere speculation; they shaped how astronomers conceptualized motion, causality, and the harmony of the spheres. The heavens were both scientifically observable and spiritually significant.

From Islam to Europe: The Legacy of Islamic Astronomy

As Europe emerged from the early medieval period, it encountered Islamic science through translations of Arabic texts into Latin. Centers like Toledo, Palermo, and Sicily became bridges between civilizations.

Works by Al-Battani, Al-Zarqali, Tusi, and others found new life in Europe. Their astronomical tables were used by medieval astronomers and navigators, including Columbus. Copernicus cited several Muslim astronomers in his revolutionary De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

Though Islamic astronomers did not break with geocentrism, their mathematical innovations, critiques of Ptolemy, and precise observations set the stage for the scientific revolution.

A Sky Remembered: The Enduring Legacy

By the 15th century, the political and economic landscape of the Islamic world began to shift. Patronage for pure science declined, and religious orthodoxy grew more suspicious of speculative inquiry. But the achievements of the Islamic Golden Age in astronomy endured.

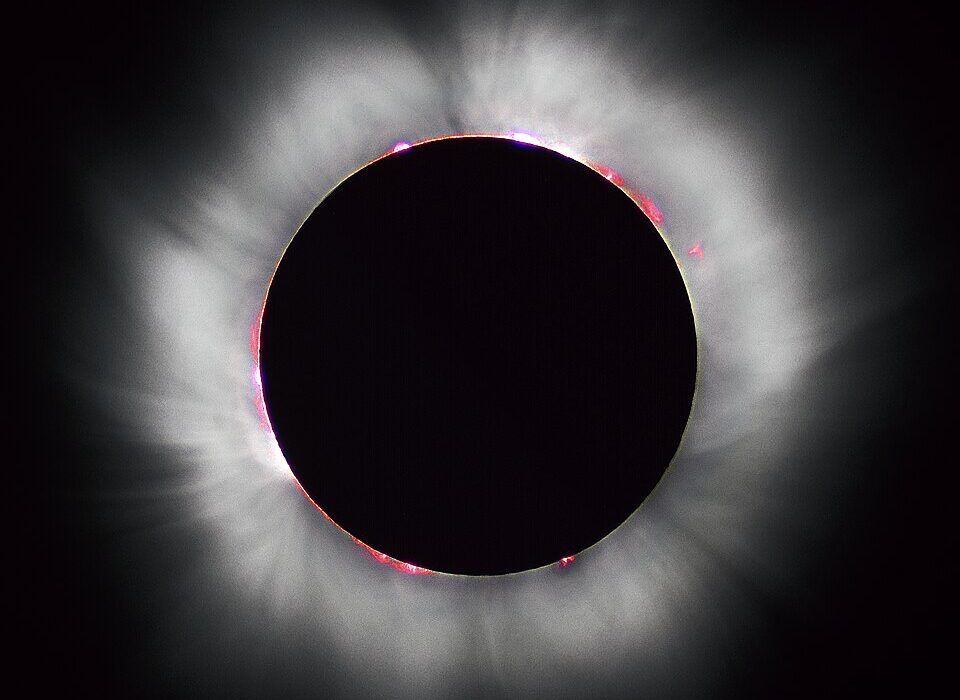

In many ways, the sky became a canvas upon which Islamic civilization painted some of its greatest achievements. Observatories rose like temples to reason. Instruments gleamed with polished brass and engraved numbers. Scholars sat beneath domed ceilings, calculating the paths of planets as the muezzin’s call echoed across ancient cities.

Even today, the contributions of these medieval astronomers resonate. Their instruments sit in museums; their names—like Al-Battani, Tusi, and Ulugh Beg—are carved on craters of the Moon. And their spirit of inquiry continues to inspire.

The Islamic Golden Age reminds us that science is not bound by geography, language, or faith. It is a shared human endeavor, born from the desire to look upward and ask not only what is there, but also why it is so. In the quiet turning of the stars and the patient work of the astronomer, we find both humility and grandeur—a legacy as timeless as the night sky.