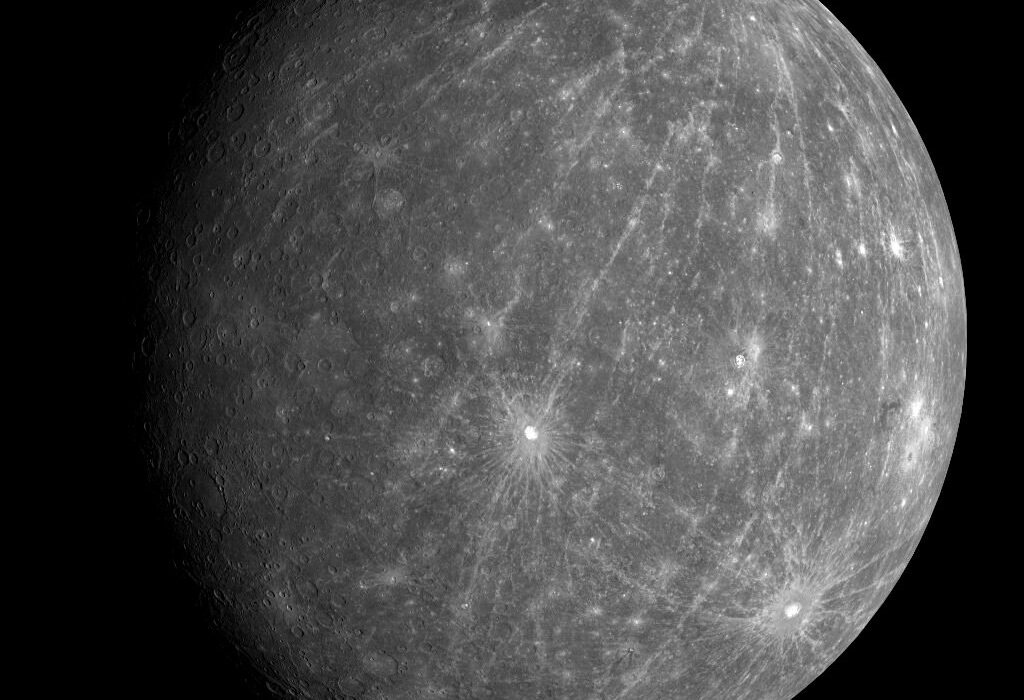

Just 34 light-years away, tucked within the constellation of Virgo, lies a faint, red star known as Gliese 536—or GJ 536, as astronomers often call it. Though invisible to the unaided eye, this small M-dwarf star has become the focus of intense astronomical study. Unlike the Sun, GJ 536 is smaller, cooler, and quieter. Yet its quietness makes it an excellent candidate in the search for planets, because subtle gravitational wobbles in its light are easier to detect.

At first glance, Gliese 536 might not seem extraordinary. It is about half the Sun’s size and mass, with a surface temperature of just 3,641 Kelvin—less than two-thirds that of our own star. At around 4.2 billion years old, it is a middle-aged star, still stable, still shining. But what makes Gliese 536 remarkable is not the star itself, but what orbits it.

The First Discovery: GJ 536 b

In 2017, astronomers detected the first known planet around this star: GJ 536 b, a world far larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. It was identified as a super-Earth, weighing in at a minimum of 6.37 times Earth’s mass. Unlike Earth, however, this planet orbits scorchingly close to its star—just 0.067 astronomical units (AU), or less than one-fifteenth the distance between Earth and the Sun.

The result is a world that sizzles with an equilibrium temperature of about 451 Kelvin (178 °C), hotter than any place on Earth. Life as we know it would find such conditions inhospitable, but the discovery was nonetheless exciting. It revealed that GJ 536 was not alone. It had company.

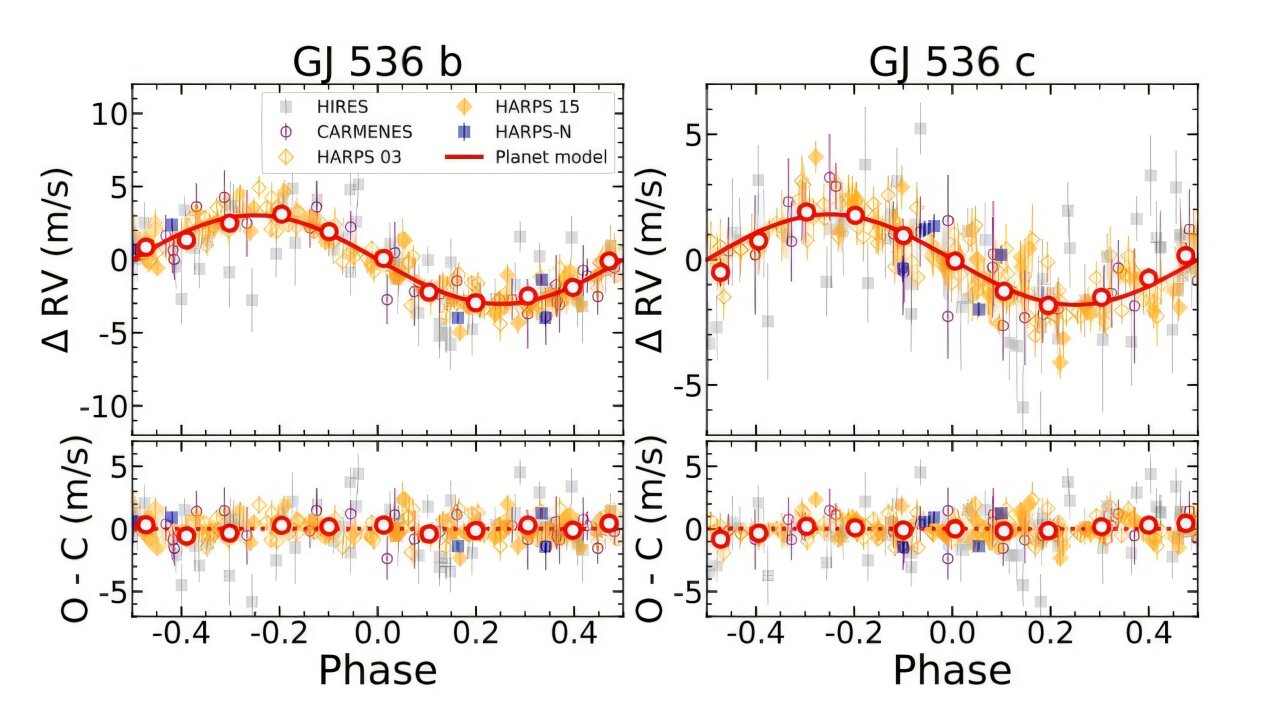

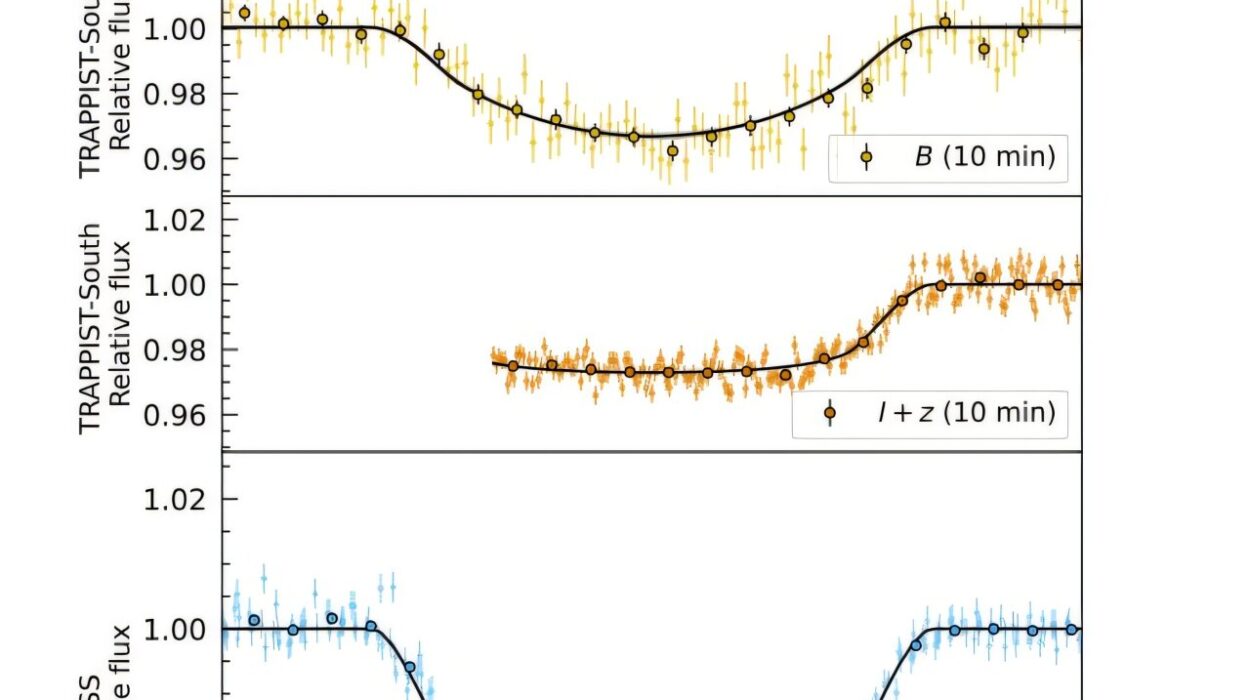

The Radial Velocity Method: Listening to a Star’s Wobble

The story of how these planets were found is as fascinating as the planets themselves. Astronomers rely on a technique called the radial velocity method, often nicknamed the “Doppler wobble” method. Here’s how it works:

As a planet orbits its star, gravity binds the two together in a cosmic tug-of-war. The planet circles the star, but the star also moves ever so slightly in response. This subtle back-and-forth motion causes the star’s light to shift—its spectral lines swing toward the blue as it moves toward us and toward the red as it moves away. By measuring these shifts with exquisite precision, astronomers can infer the presence of a planet, its mass, and its orbit, even if they never see the planet directly.

This method has already uncovered over 600 exoplanets and continues to be one of the most reliable tools for hunting worlds beyond our solar system.

A Second Planet Emerges: GJ 536 c

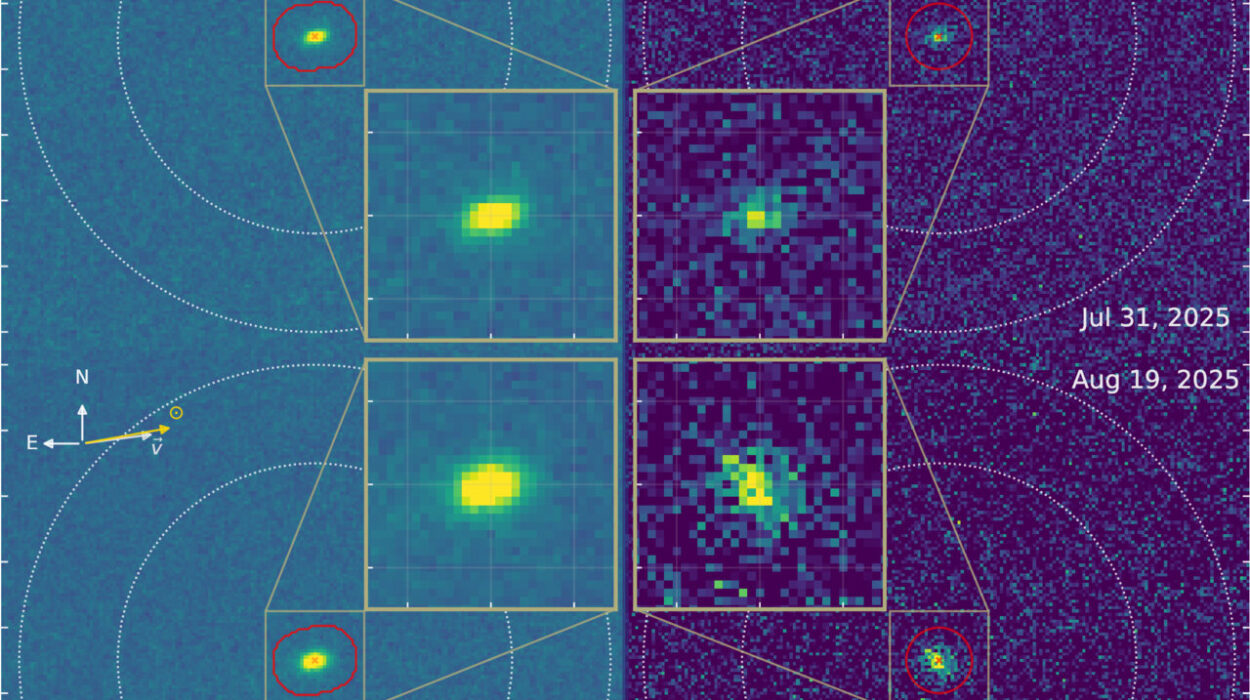

Now, in a careful re-examination of archived data from some of the world’s most powerful spectrographs—including HARPS, HARPS-N, CARMENES, and HIRES—an international team led by Alejandro Suárez Mascareño has uncovered a second planet around Gliese 536.

This newly discovered world, GJ 536 c, is also a super-Earth, with a minimum mass of 5.89 Earth masses. Unlike its sibling, however, it orbits farther out, completing a revolution every 32.76 days at a distance of 0.16 AU from its star. Its equilibrium temperature is estimated at around 290 Kelvin (about 17 °C)—eerily close to Earth’s own average temperature.

For astronomers, this is an extraordinary find. While GJ 536 c still receives more stellar radiation than Earth—slightly less than Venus in our solar system—it resides in a region tantalizingly near the habitable zone, where liquid water might potentially exist under the right conditions.

The Question of Habitability

Does this mean GJ 536 c could harbor life? The answer is complicated. Its closeness to its host star raises questions about atmospheric stability. Red dwarfs, especially younger ones, are notorious for stellar flares that can strip planetary atmospheres and irradiate surfaces. However, GJ 536 appears relatively quiet compared to many of its M-dwarf cousins.

What excites researchers is not certainty of habitability, but possibility. At 34 light-years away, GJ 536 c is close enough to become a target for future atmospheric studies. Instruments that can analyze a planet’s reflected light, like those aboard upcoming space telescopes, could reveal whether this super-Earth possesses an atmosphere, and if so, whether that atmosphere bears the chemical fingerprints of habitability.

In the near future, GJ 536 c could be among the first small exoplanets where astronomers attempt to study atmospheric composition in detail. That makes it not just another discovery, but a stepping stone toward answering the greatest question of all: Are we alone?

The Dynamic Star Behind the Planets

The star itself adds intrigue to the system. Observations suggest GJ 536 rotates every 43.63 days, with surface features dominated by star spots and bright plages surrounding them. These features can mimic or obscure planetary signals, which is why careful long-term monitoring was required to confirm GJ 536 c’s existence. The detection is a testament to the patience and precision of astronomers who sift through years of stellar data, separating planetary whispers from stellar noise.

Rediscovering the Past to Find the Future

One of the most inspiring aspects of this discovery is how it came to light. GJ 536 c was not revealed by new observations but by a meticulous reanalysis of existing ones. Data from instruments across continents—Chile’s HARPS, Spain’s CARMENES, Hawaii’s HIRES, and the Italian HARPS-N—were pooled together, carefully untangled, and interpreted anew.

This demonstrates a powerful truth: sometimes, the universe’s secrets are already hidden in plain sight, waiting for us to look again with sharper eyes and wiser minds.

Why This Matters

Every new planet discovered around a nearby star is a reminder that our solar system is not unique. Super-Earths like GJ 536 b and c are the most common type of planet in the galaxy, though none exist in our own solar system. To study them is to explore a category of world that is alien to us, yet ubiquitous elsewhere.

Moreover, the proximity of GJ 536 makes it an excellent laboratory for testing methods of atmospheric detection. The possibility that GJ 536 c could one day reveal its skies, its weather, perhaps even its chemistry, is profoundly moving. It draws us one step closer to answering whether Earth is an oasis—or one among countless other habitable worlds.

A Cosmic Invitation

In the vast tapestry of the universe, discoveries like GJ 536 c remind us that the search for other worlds is more than science—it is an extension of human wonder. To find a planet that could, under the right conditions, echo aspects of our own home is to feel the pull of cosmic kinship.

The system of Gliese 536 is now known to host at least two super-Earths, one scorched and one temperate. What lies beyond them? More planets may yet orbit in the shadows, waiting for us to uncover their presence. Each new discovery whispers an invitation to keep looking, to keep questioning, and to keep reaching outward.

For now, we know this: a faint red star, 34 light-years away, is no longer just another dot in the sky. It is a solar system with a story, one that binds us to it through curiosity, science, and the timeless human longing to find our place in the universe.

More information: Alejandro Suárez Mascareño et al., A second low-mass planet orbiting the nearby M-dwarf GJ 536, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202555731. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.03134