Imagine waking up one morning. You stretch, feel the warmth of sunlight against your skin, hear the distant hum of traffic, smell the faint aroma of coffee, and recognize yourself as the one who is awake, perceiving it all. These sensations and awareness are not just raw data — they are your experiences. But why does this inner world exist? Why is there something it feels like to be you?

This is the question that has haunted philosophers, scientists, and thinkers for centuries. It has been called the “hard problem of consciousness.” The term was popularized in the 1990s by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers, though the mystery itself is ancient. While science has made breathtaking progress in mapping the brain, explaining memory, perception, and behavior, a profound question remains unanswered: Why should all of this processing inside the brain give rise to subjective experience — to the feeling of being alive?

Understanding the “hard problem” requires a journey through philosophy, neuroscience, and the very limits of human understanding. But at its heart, the issue can be explained simply: Why is the brain not just a machine that processes information, but also a source of inner experience? Why is there a “you” inside your head at all?

The Easy Problems and the Hard Problem

To appreciate the mystery, we must first separate what Chalmers called the “easy problems” of consciousness from the “hard problem.”

The easy problems are not trivial — they are vast scientific challenges. They involve explaining how the brain discriminates stimuli, integrates information, controls behavior, forms memories, and allows attention. For example, how do neurons in the retina and visual cortex work together to let us recognize a friend’s face? How does the hippocampus allow us to recall a childhood memory? These questions are enormously complex, but in principle they can be answered by studying mechanisms. We can imagine a day when science will map every neuron and chemical in the brain to account for perception, memory, and decision-making.

The hard problem, however, is different. Even if we knew every detail about how the brain works, we would still be left asking: Why does all this activity feel like something? Why isn’t the brain a mere computational engine with no inner life, no subjective glow, no sense of self? Why does pain hurt, and why does chocolate taste sweet? Why isn’t the brain simply dark and silent from the inside?

This leap from physical processes to lived experience is what makes the hard problem so perplexing. It is not about function, but about experience itself. Science can tell us how neurons fire when we touch something hot, but not why that firing is accompanied by the burning sensation of pain.

The Long History of Wonder

The hard problem is not new. In some ways, it is as old as human reflection itself. Ancient Indian philosophers pondered the nature of consciousness in the Upanishads thousands of years ago, asking what it means to be the witness of experience. In ancient Greece, thinkers like Plato and Aristotle debated the soul and its relationship to the body.

In the 17th century, René Descartes made the problem famous in Europe. He argued for dualism — the idea that mind and body are distinct substances. The body, he believed, was a machine governed by physical laws, while the mind was immaterial, belonging to a different realm. This “Cartesian dualism” has since been rejected by most scientists, but the question it raised — how consciousness arises from matter — remains central.

Later, philosophers like John Locke, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant wrestled with the nature of subjective experience. They recognized that while we can study the world through science, what we truly know directly is the theater of consciousness itself — our perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. The external world is always filtered through this inner medium.

In the modern age, neuroscience has revealed staggering details about the brain. We know about neurons, synapses, neurotransmitters, and networks. We can scan the brain with fMRI, measure electrical signals, and even manipulate brain activity with stimulation. Yet, for all this knowledge, the gap remains: how do these electrochemical events become the redness of red, the ache of longing, or the joy of music?

What Consciousness Feels Like

To truly understand the hard problem, we need to pause and notice our own experience. Consciousness is not an abstract puzzle; it is the most intimate fact of our lives. At this moment, you are not merely reading words — you are experiencing them. There is the awareness of the screen before you, perhaps the sounds around you, the position of your body, the subtle emotions of curiosity or interest. This flow of subjective awareness is consciousness.

Philosophers often call these subjective qualities “qualia.” The redness of a rose, the bitterness of black coffee, the sound of a violin — these are qualia, the raw feels of experience. We can describe them, measure the wavelengths of light or the frequencies of sound, but the “what it is like” to perceive them is only accessible from the inside.

Thomas Nagel captured this beautifully in his famous 1974 essay, “What is it like to be a bat?” He argued that even if we knew everything about a bat’s brain and echolocation system, we would still not know what it feels like to be a bat. Consciousness, in this sense, has an irreducibly subjective dimension.

This is why the hard problem strikes us so deeply. Science thrives on objectivity — on third-person measurements. But consciousness is first-person, known only from within. Bridging these two perspectives seems almost impossible.

Neuroscience and the Correlates of Consciousness

Despite the difficulty, scientists have made progress in understanding the brain activity that goes hand in hand with consciousness. These are called the “neural correlates of consciousness.” Researchers study which patterns of brain activity appear when a person is aware versus unaware.

For example, if you flash an image on a screen so briefly that someone does not consciously notice it, their brain still shows some activity. But when they do notice it, additional widespread networks light up, particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes. Conscious perception seems to involve not just local processing but global broadcasting across the brain — a kind of ignition that brings information into awareness.

Other studies focus on the thalamus, a deep brain structure that integrates signals, and on synchronized rhythms between different brain areas. Theories such as Global Workspace Theory and Integrated Information Theory attempt to explain these patterns. They suggest that consciousness arises when information is globally available for decision-making, or when information is highly integrated into a unified whole.

These approaches are fascinating, but they describe the “easy problems.” They explain how information is processed in conscious states, but not why processing should be accompanied by experience. They may tell us which circuits light up when we see red, but not why those circuits create the subjective redness. The hard problem remains untouched.

Materialism and Its Limits

Most modern scientists adopt some form of materialism — the belief that consciousness must arise from physical processes in the brain. After all, when the brain is damaged, consciousness is altered. Drugs, anesthesia, and electrical stimulation all change subjective experience. Consciousness seems deeply tied to brain activity.

Yet materialism struggles with the hard problem. How does matter — neurons and chemicals — produce qualia? How does physical motion give rise to the taste of chocolate or the sadness of loss? Saying “it just does” feels unsatisfying. It risks becoming what philosophers call a “brute fact” — an unexplained given.

Some argue that once we fully understand the brain, consciousness will no longer seem mysterious, just as life once seemed inexplicable until biology revealed DNA and evolution. Others insist that the gap is fundamental, that consciousness cannot be reduced to matter alone.

Alternative Perspectives

In light of this struggle, thinkers have proposed bold alternatives. Some suggest panpsychism — the idea that consciousness is a fundamental feature of matter, present in some form even at the smallest scales. In this view, atoms and particles may have rudimentary “proto-consciousness,” which becomes richer as systems become more complex. Panpsychism avoids the leap from matter to mind by declaring that mind is already woven into matter.

Others turn to dual-aspect theories, suggesting that reality has both a physical and a mental aspect, two sides of the same coin. Just as light can be seen as both wave and particle, perhaps reality has a double nature, with consciousness as intrinsic as matter.

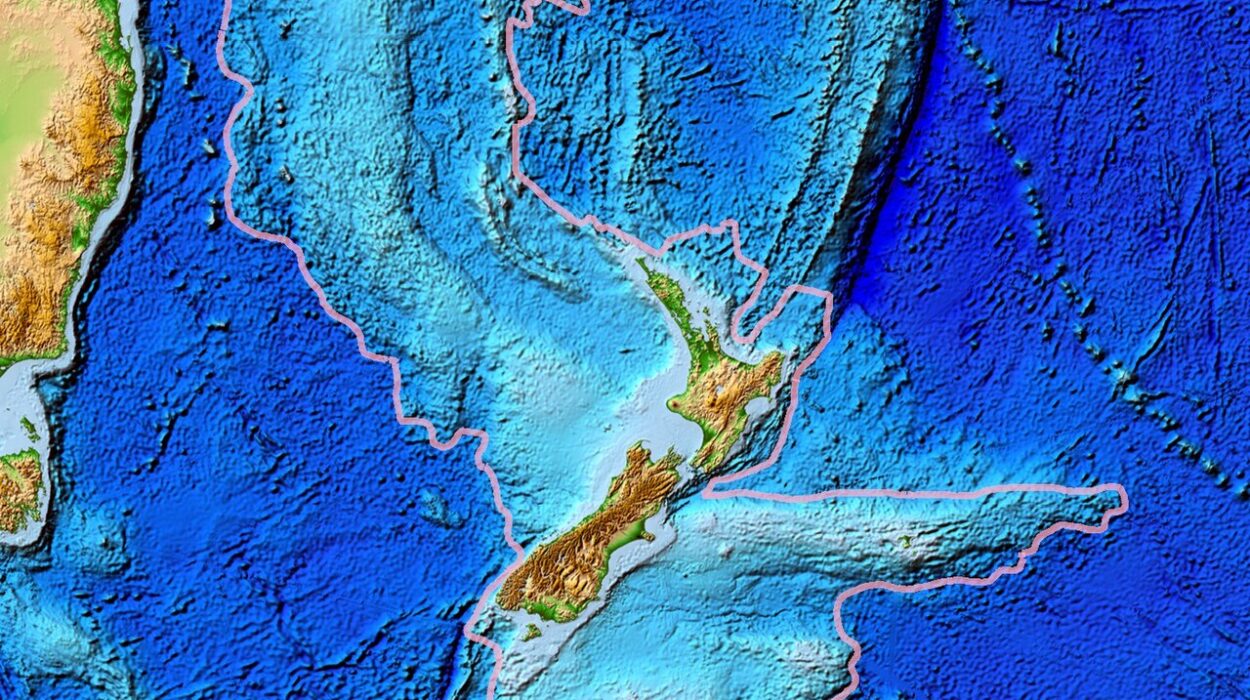

Some scientists even explore quantum theories, proposing that consciousness arises from quantum processes in the brain, where indeterminacy and entanglement play a role. These ideas are highly speculative but attempt to tackle the mystery at its roots.

Still others argue for illusionism — the view that consciousness, as we think of it, is an illusion created by the brain. According to illusionists, there is no “hard problem,” only the brain generating a convincing story that feels like subjective experience. This view is provocative and unsettling, raising questions about what it means for our sense of self to be real.

Why the Hard Problem Matters

The hard problem is not a mere academic puzzle. It strikes at the core of what we are. Consciousness is the seat of our joys and sorrows, our loves and hopes, our identities. Without it, there would be no meaning, no value, no world as we know it.

Understanding consciousness also has practical implications. It could transform medicine, especially in treating disorders of awareness like coma, anesthesia, or dementia. It could reshape artificial intelligence, helping us know whether machines can truly be conscious or merely simulate it. It could influence ethics, determining which beings deserve moral consideration. If animals or AI are conscious, how should we treat them?

At a deeper level, the hard problem confronts us with humility. It reminds us that even as we map the galaxies and split the atom, we do not fully understand the mind that does the mapping and splitting. We remain a mystery to ourselves.

Living with the Mystery

So where does this leave us? Perhaps the hard problem will one day be solved, with a conceptual breakthrough as radical as relativity or quantum mechanics. Perhaps consciousness will be revealed as a fundamental property of the universe, or as an emergent phenomenon we have yet to fully grasp. Or perhaps the mystery will endure, always at the horizon of human thought.

What matters is that the hard problem invites us to marvel at our own existence. Every moment of awareness is a miracle we do not yet understand. To feel the sun, to taste coffee, to love, to dream — these are not just accidents of biology but profound mysteries.

Albert Einstein once said that the most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious, for it is the source of all true art and science. The hard problem of consciousness is precisely this kind of mystery. It humbles us, inspires us, and reminds us that being alive is far stranger and more wondrous than we usually admit.

Toward a Deeper Understanding

Perhaps the solution will require new frameworks, beyond current science. Just as Newtonian physics gave way to relativity, perhaps our materialist assumptions will give way to a broader conception of reality. Perhaps mind and matter are not separate, not reducible one to the other, but parts of a deeper whole.

Until then, the hard problem remains a kind of compass. It points us toward the deepest questions of existence, urging us to explore not only the outer universe but also the inner one. It asks us not just to solve puzzles but to reflect on the meaning of being.

And in doing so, it makes us conscious not just of consciousness itself, but of the sheer miracle of being aware at all.