In the palm of your hand lies a marvel—a device of such technological complexity and power that it would have seemed like magic just a few decades ago. With a tap, you can summon a car, book a flight, chat with friends across the world, monitor your heart rate, track your sleep, and order groceries without speaking to a single human being. The digital age has gifted us with speed, efficiency, and comfort beyond imagination. It has made the world smaller and our lives seemingly easier.

But like all gifts of great power, this one comes with a cost. The invisible currency we often pay for these conveniences isn’t money. It’s our data—our most personal thoughts, habits, desires, and behaviors. And unlike cash or credit, once that currency is spent, it can never truly be reclaimed.

We’re living in a world where surveillance has been normalized, where “smart” often means “watched,” and where privacy, once a sacred human right, is being quietly eroded beneath the sheen of innovation.

Digital Footprints in a Virtual World

Every move we make online leaves a trail—a breadcrumb path of digital behaviors that tells a story about who we are. This trail, known as a digital footprint, includes everything from the websites we visit to the locations we frequent, from the keywords we search to the items we browse but don’t buy. Even our pauses—how long we linger on an image or hover over a piece of text—are recorded and analyzed.

Most of us never read the terms and conditions we agree to. We scroll past them, eager to install the app, access the feature, unlock the content. In doing so, we often grant sweeping permissions: access to our camera, microphone, contacts, location, and more. These apps, in turn, collect data relentlessly, even when they are not in use.

The justification is always framed in terms of personalization. Tech companies promise tailored experiences—smarter suggestions, better ads, improved services. But the trade-off is steep. Our lives are being dissected into data points, fed into algorithms, and auctioned to advertisers, governments, and unknown third parties.

From Smart Homes to Surveillance Hubs

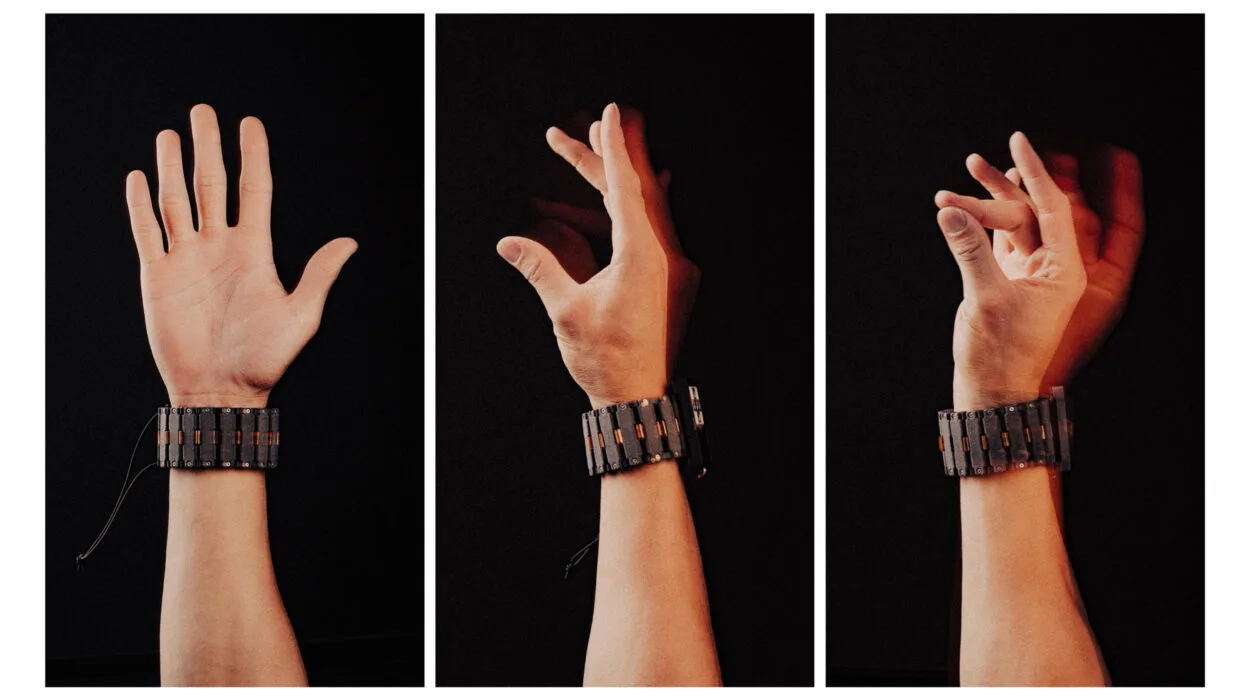

The home used to be the last bastion of privacy. But with the rise of smart devices—voice assistants, internet-connected appliances, security cameras, and smart TVs—even our most intimate spaces are becoming nodes in a surveillance network.

Voice-activated assistants like Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant are always listening. While they claim to only activate upon hearing their “wake word,” research has shown that they sometimes record audio unintentionally. These snippets are stored in the cloud, where they can be analyzed by both humans and machines.

Smart TVs can track what you watch and how long you watch it. Some models even include facial recognition and eye-tracking software. Security cameras, often installed for protection, can stream your front door—or your entire living room—to servers halfway around the world.

Even your thermostat may be monitoring you. Smart thermostats learn your schedule, know when you’re home or away, and gather data about your routines. In isolation, this data might seem harmless. But in aggregate, it forms a vivid picture of your daily life—when you sleep, when you shower, when you eat, when you’re on vacation.

The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

At the heart of this data collection lies a powerful economic engine: surveillance capitalism. Coined by Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff, the term describes a new economic logic where human experience is mined as raw material for profit.

Google, Facebook, Amazon, and countless others don’t sell products in the traditional sense—they sell attention, behavior, and prediction. Your data is used to create behavioral models that forecast what you will do next, what you might buy, how you might vote, where you might go. These models are then sold to advertisers, political campaigns, insurance companies, and more.

The most valuable commodity is no longer oil or gold. It’s your attention, and more specifically, your predictable behavior.

And it’s not just for selling sneakers. This data can be used to influence opinions, shape ideologies, and manipulate emotions. The algorithms that power your social media feed are not neutral. They are designed to keep you scrolling, to provoke outrage, to reinforce biases, and to serve ads with precision.

Convenience as a Trojan Horse

We welcome new technologies into our lives because they make things easier. But convenience often masks control. The more seamlessly a technology integrates into our routines, the less we question its presence—and its implications.

Consider facial recognition. It’s undeniably convenient: unlocking phones, automating photo tagging, enhancing security. But it’s also one of the most powerful surveillance tools ever created. In authoritarian regimes, it’s used to monitor dissidents, suppress protests, and control populations. In democratic societies, it’s creeping into police departments, airports, and retail stores—often without public debate or transparency.

Or take location tracking. Apps that tell you the fastest route home, the nearest restaurant, or when your ride will arrive rely on constant geolocation. That data can be used to reconstruct your movements in chilling detail. During protests, some governments have used location data to identify and intimidate participants.

The problem isn’t the technology itself—it’s how it’s used, who controls it, and what it’s used for. The tools we adopt for convenience may one day be used against us in ways we can’t yet imagine.

The Illusion of Control

Many tech platforms offer privacy settings, giving users the illusion of control. You can turn off certain data sharing, limit ad personalization, or delete your history. But these settings are often buried, confusing, or deceptive.

Studies show that even when users adjust their settings, data collection often continues. A 2018 investigation by the Associated Press found that Google continued to track users’ locations even after they turned off “Location History.” The data simply went into a different category.

This dark pattern design—interfaces deliberately created to manipulate users into sharing more than they intend—is widespread. Platforms exploit human psychology, nudge behavior, and make opting out harder than opting in.

Consent, under these conditions, is not truly informed. It’s coerced, obfuscated, or irrelevant.

Children in the Crosshairs

Perhaps the most vulnerable to this surveillance economy are children. From the moment they are born, their digital lives begin—often before they can speak. Parents post photos, videos, and milestones, building a detailed digital dossier for an audience of friends—and unseen algorithms.

Educational apps, online games, and YouTube channels aimed at children collect data in ways parents often don’t realize. This data can be used to target ads, personalize content, and, in some cases, profile behavior.

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) offers some legal protection in the U.S., but enforcement is spotty, and many platforms operate in legal gray zones or outside U.S. jurisdiction altogether.

Growing up in a world where constant monitoring is normal may shape how the next generation views privacy—not as a right, but as an outdated concept.

The Psychological Toll

Privacy isn’t just a legal issue or a political one. It’s deeply personal and psychological. Knowing that you are being watched changes how you behave. This phenomenon, known as the “panopticon effect,” was first described by philosopher Jeremy Bentham and later explored by Michel Foucault.

In a digital panopticon, we become self-censoring, less creative, more compliant. We second-guess our searches, our posts, our jokes. The sense of being observed—even by a machine—can induce stress, anxiety, and a loss of autonomy.

This erosion of mental space may be one of the most insidious effects of the surveillance age. It turns private thought into public record, and free expression into an algorithmic calculation.

Who Owns Your Data?

At the center of the privacy debate is a fundamental question: who owns your data?

Most tech companies act as if they do. When you use their platforms, you generate data. That data is stored on their servers, analyzed by their algorithms, and monetized by their business models.

But this raises ethical dilemmas. Your health data can reveal vulnerabilities. Your financial data can expose your wealth or debt. Your search history can uncover your fears, hopes, and secrets. Should corporations have unrestricted access to this intimate knowledge?

Some argue that data should be treated like property—owned, controlled, and possibly sold by the individual. Others argue that privacy is a human right, not a commodity.

Laws like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) attempt to address this by granting users more control, transparency, and the “right to be forgotten.” But enforcement is patchy, and compliance is often more about optics than substance.

Technology and Tyranny

The tools of surveillance, once reserved for spies and authoritarian states, are now available to anyone with the right software. Governments use them to monitor citizens. Employers use them to watch workers. Abusive partners use them to track victims.

Even democracies are not immune. National security is often cited as a justification for expanded surveillance powers. After 9/11, the U.S. government vastly increased its ability to collect phone records, monitor emails, and track financial transactions—often without warrants.

Edward Snowden’s revelations in 2013 exposed the scope of this surveillance, sparking global outrage. But over time, that outrage faded, and many of the programs remained intact or evolved into even more sophisticated systems.

Today, the lines between public safety, corporate profit, and personal freedom are more blurred than ever.

Can We Have Both Privacy and Progress?

This is the crux of the dilemma: must we choose between privacy and progress, or can we have both?

Some technologists believe privacy-focused design is not only possible but necessary. End-to-end encryption, decentralized networks, anonymization protocols, and user-owned data platforms are part of a growing movement to rebuild the internet around individual rights rather than corporate interests.

Signal, a secure messaging app, offers encryption by default and collects minimal metadata. DuckDuckGo promises search without tracking. The Brave browser blocks ads and trackers by design.

But these tools remain niche. Most people continue to use the platforms that offer the most convenience—even if they demand the highest privacy cost.

The challenge isn’t just technological—it’s cultural and educational. People need to understand what’s at stake, why it matters, and how they can push for change.

The Path Forward

The future of privacy will be shaped by choices made today—by individuals, companies, lawmakers, and technologists. Regulation will play a role, but so will public pressure, consumer behavior, and ethical innovation.

Education is essential. People need to know how their data is used, who profits from it, and what alternatives exist. Schools must teach digital literacy, not just coding skills but critical thinking about technology’s impact on society.

Transparency must become a standard, not a rarity. Companies should be required to explain, in plain language, what data they collect and why. Default settings should favor privacy, not exploitation.

And perhaps most importantly, we need to redefine our relationship with technology. Instead of asking how tech can serve corporations, we must ask how it can serve humanity—without stripping us of our dignity, our freedom, and our right to be left alone.

The Final Trade-Off

The conveniences of modern technology are undeniable. But the true cost is not measured in dollars or minutes saved. It is measured in autonomy, trust, and identity.

Privacy is not nostalgia. It is not a barrier to progress. It is the foundation of liberty, the bedrock of intimacy, and the safeguard of democracy.

In a world where technology is always listening, always watching, and always learning, the question is no longer whether we are sacrificing privacy for convenience. The question is how much we are willing to lose before we realize what cannot be bought back.

We stand at a crossroads. One path leads to empowerment, balance, and ethical design. The other leads to a society where privacy is a memory and surveillance is the norm.

The choice is still ours—but only if we dare to open our eyes and make it.