Memory is at once the most ordinary and the most extraordinary function of the human mind. It shapes who we are, stores the stories of our lives, and connects us to the world. Every familiar face, every word we speak, every skill we learn rests on the scaffolding of memory. Without it, there is no identity, no continuity, no self. Yet, for all its importance, memory is astonishingly fragile. It bends, distorts, and sometimes vanishes altogether. We remember things that never happened, forget things we swore we would never lose, and sometimes cannot find the right word for something as simple as a spoon. To understand how memory works, and why it so often fails, we must travel into the brain’s hidden networks and explore the mysteries of the mind’s most elusive power.

The Architecture of Remembering

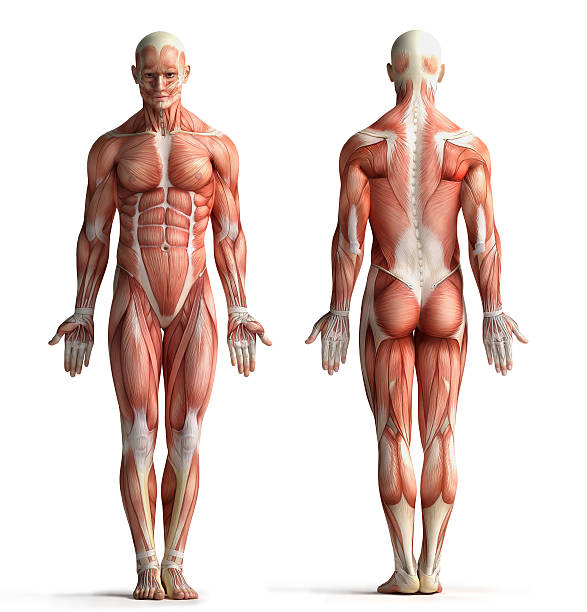

At its core, memory is not a single thing but a complex web of processes spread across different brain systems. The hippocampus, nestled deep within the temporal lobe, acts like a master archivist, binding pieces of an experience together into a coherent memory. The amygdala stamps emotional significance onto those experiences, making joyful or traumatic moments far more vivid. The prefrontal cortex orchestrates the retrieval and manipulation of stored knowledge, allowing us to use memories in reasoning and planning.

When we encounter something new, sensory regions of the brain capture its details—the sound of a friend’s voice, the color of a sunset, the scent of jasmine. The hippocampus then links these fragments into a single memory trace. This process is called encoding. From there, the memory is gradually consolidated, transferred into long-term storage through changes in synaptic connections between neurons. These changes, known as long-term potentiation, physically alter the brain’s wiring, strengthening certain pathways so that the memory can be accessed later.

Memory, therefore, is not like a video recording but more like a living tapestry. Every recall is a reconstruction, woven anew from patterns of neural activity. This is both its strength and its weakness: memories can adapt and evolve, but they can also warp and unravel.

The Many Faces of Memory

Not all memory is created equal. Scientists distinguish between multiple forms, each with its own function and vulnerability. Episodic memory allows us to relive personal experiences—the day of a wedding, the sound of childhood laughter, the feeling of holding a newborn child. Semantic memory stores facts and knowledge, the capital of France, the meaning of a word, the rules of arithmetic. Procedural memory governs skills and habits—how to ride a bicycle, play the piano, or type without looking at the keyboard.

There is also working memory, the mind’s scratchpad, which temporarily holds information in a fragile, easily lost state. It is what allows us to keep a phone number in mind long enough to dial it, or to follow the thread of a conversation. Working memory is like juggling balls in the air—once you stop paying attention, they fall.

These different forms are not isolated silos but overlapping processes. When you learn to drive, you draw on working memory to follow instructions, semantic memory to recall traffic laws, episodic memory to remember past lessons, and procedural memory to automate the motions of steering and braking. Together, they weave the fabric of everyday life.

Why We Forget

Forgetting is often viewed as a failure, but in reality, it is a crucial part of memory. If we remembered everything indiscriminately, our minds would be cluttered with useless detail. Forgetting allows us to prune away the irrelevant, making room for what matters. Yet sometimes the pruning goes too far. We forget the name of someone we just met, the location of our keys, or the reason we walked into a room.

One major cause of forgetting is decay. Memory traces fade over time if not revisited or reinforced, like footprints washed away by waves. Another culprit is interference. New memories can overwrite old ones, or old ones can block access to new ones. This is why it is easier to learn a second language if it is different from your native tongue; otherwise, interference from familiar words causes confusion.

Retrieval failures also play a role. A memory may be stored but inaccessible in the moment, as when a word is on the “tip of the tongue.” In such cases, a cue—hearing the first letter, or being reminded of a related detail—can bring the memory rushing back. Forgetting, then, is not always loss, but sometimes a failure of access.

The Illusions of Remembering

One of the strangest aspects of memory is its unreliability. We often think of memories as accurate snapshots of the past, yet research has shown they are prone to distortion. Each time we recall a memory, we reconstruct it, filling in gaps with assumptions and blending it with other experiences. Over time, the memory can change, sometimes drastically.

Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus demonstrated how easily false memories can be implanted. By suggesting details in a story, she was able to make people “remember” events that never occurred, such as being lost in a mall as a child. This malleability explains why eyewitness testimony, once considered the gold standard of legal evidence, is now recognized as deeply flawed.

Even without external suggestion, our minds can betray us. We might remember seeing a friend at a party when they were never there, or recall a conversation that took place differently than we believe. The brain prioritizes meaning over detail, so it often sacrifices accuracy in favor of coherence. Memory is not a camera but a storyteller, prone to embellishment and error.

Emotion and the Strength of Memory

Not all memories are equal in durability. Emotion acts as a powerful amplifier, searing experiences into the brain. The amygdala ensures that emotionally charged events—whether joyful or terrifying—are encoded more deeply. This is why many people vividly recall where they were during major world events, such as hearing about a tragedy or a triumph. These so-called flashbulb memories feel indelible, as if frozen in time.

Yet even emotional memories are not immune to distortion. Studies have shown that while people remain confident in their flashbulb memories, the details often shift over time. The intensity of emotion preserves the sense of certainty but not necessarily the accuracy. In this way, emotion makes memory feel stronger than it really is.

Traumatic memories pose a unique challenge. For some, trauma imprints memories so vividly that they intrude as flashbacks, haunting the present. For others, the mind may suppress or fragment the memory, a defense mechanism to shield against overwhelming pain. These dynamics reveal the double-edged role of emotion in the architecture of remembering.

Childhood Amnesia and the Mystery of Early Memory

Most people cannot remember events from their first few years of life, a phenomenon known as childhood amnesia. The brain of a young child is still developing, and the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are not yet mature enough to form lasting autobiographical memories. Language also plays a role; without words, experiences are harder to structure into narratives that can be recalled later.

Yet, even without explicit memories, early experiences shape us in profound ways. The emotional tone of our childhood, the love or neglect we received, the environments we grew up in—all leave lasting imprints, guiding our personalities and responses long after the details are forgotten. In this sense, memory operates on levels deeper than conscious recollection.

Memory in Aging

As we grow older, memory undergoes inevitable changes. Episodic memory tends to decline, making it harder to recall recent events or learn new names. Working memory also weakens, reducing mental flexibility. Yet not all forms of memory suffer equally. Semantic memory—our store of knowledge—often remains strong, even expanding with age. Procedural memory also tends to endure; once learned, skills like swimming or typing are remarkably resistant to time.

The aging brain also develops compensatory strategies. Older adults may rely more on cues, routines, and external supports like notes or reminders. Wisdom, which is the integration of knowledge, experience, and judgment, often grows even as certain forms of memory wane. Thus, memory in aging is not simple decline but transformation.

When Memory Breaks

For some, memory loss goes beyond normal aging. Conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia erode memory in devastating ways. In Alzheimer’s, the buildup of plaques and tangles disrupts neural communication, leading to the gradual disintegration of memory networks. First go the recent events, then older memories, and eventually even the knowledge of loved ones’ faces.

Other conditions, such as amnesia caused by brain injury, reveal the fragility of memory systems. Patients with damage to the hippocampus may lose the ability to form new memories while retaining old ones, living in a perpetual present. These cases, tragic as they are, provide profound insight into how memory works by showing what happens when it fails.

The Role of Sleep

One of the most underappreciated forces in memory is sleep. During deep sleep, the brain replays patterns of activity from the day, strengthening synaptic connections and consolidating memories. Dreams, strange and surreal as they are, may be part of this process, weaving experiences into broader networks of meaning.

Sleep deprivation, by contrast, wreaks havoc on memory. Without adequate rest, encoding falters, consolidation weakens, and retrieval becomes unreliable. Students cramming overnight may feel productive, but their exhausted brains betray them during exams. Sleep is not wasted time but essential maintenance for the architecture of memory.

Technology and the Externalization of Memory

In the modern world, memory is increasingly outsourced to technology. We no longer need to memorize phone numbers, maps, or even facts; a smartphone does it for us. This convenience reshapes the way we use memory. Rather than storing raw information, we store knowledge of where to find it. Psychologists call this the “Google effect.”

Some lament this as the decline of memory, but it may be more accurate to see it as evolution. Human culture has always relied on external memory—first in oral traditions, then in writing, then in print, and now in digital form. The danger lies not in forgetting details, but in losing the ability to think critically, to connect, and to reflect. Technology may store facts, but meaning still depends on the human mind.

Memory and Identity

Memory is not just a function of the brain but the foundation of the self. Our memories tell us who we are, where we have been, and what we value. They link us to our families, our cultures, and our personal histories. To lose memory is not merely to forget but to lose a piece of identity.

Yet memory is also selective, and identity is shaped as much by what we forget as by what we remember. We highlight certain stories, suppress others, and weave a narrative that makes sense of our lives. In this way, memory is not a static archive but an ongoing act of creation. Who we are is, in large part, the story we tell ourselves with the materials memory provides.

The Future of Memory

Neuroscience is only beginning to unravel the complexities of memory. New technologies, from brain imaging to optogenetics, allow scientists to observe and even manipulate memory circuits in unprecedented detail. Experiments with mice have shown it is possible to erase or implant specific memories by activating certain neural patterns. One day, therapies may allow us to repair damaged memory, treat trauma, or enhance learning.

But such power carries ethical challenges. Should we erase painful memories, knowing that they shape resilience and wisdom? Should we enhance memory artificially, widening the gap between those who can afford it and those who cannot? As with all technologies, the future of memory science will demand careful balance between possibility and responsibility.

The Mystery Endures

Despite decades of research, memory remains one of the deepest mysteries of the mind. It is a fragile miracle, capable of astonishing feats and yet riddled with flaws. We rely on it to tell us who we are, even as it deceives us with distortions and forgetfulness. Perhaps this very imperfection is part of its beauty. Memory is not mechanical but human—messy, emotional, and alive.

To remember is to relive, to connect, to carry the past into the present. To forget is to clear space for new beginnings. And between remembering and forgetting lies the essence of being human: a self in motion, shaped by fragments of the past, always reaching into the future.