Earth isn’t just a planet of life—it’s a planet of connected life. From the dense forests of the Amazon to the icy deserts of Antarctica, from the deepest ocean trenches to your own backyard, life doesn’t exist in isolation. It forms networks, communities, and systems—what scientists call ecosystems. These are not just clusters of organisms sharing a space; they are intricate webs of interaction, competition, cooperation, and transformation.

At the heart of every ecosystem lies a fundamental truth: nothing survives alone. Even the most solitary creature is part of a grander design. The tiger depends on the forest to shelter its prey. The coral relies on microscopic algae to build its colorful fortress. And humans—despite skyscrapers, smartphones, and cities—are still bound by the rules of nature’s game.

Ecosystems are nature’s blueprint for sustainability. They demonstrate resilience, adaptability, and elegance. Yet in the face of climate change, habitat destruction, and human expansion, these systems now tremble. Understanding how ecosystems work—and how we are a part of them—may be the key to not only conserving life on Earth but also redefining our place within it.

The Architecture of Life: What Makes an Ecosystem?

To the untrained eye, a forest might appear as a random assembly of trees, birds, and insects. But step closer, and you’ll find structure, order, and hierarchy.

An ecosystem is a biological community of interacting organisms—and the physical environment with which they exchange energy and matter. It includes all living components (the biotic factors): animals, plants, fungi, bacteria. And it includes non-living elements (the abiotic factors): sunlight, temperature, water, soil, nutrients, and gases.

Energy flows through an ecosystem primarily via the sun. Plants capture sunlight through photosynthesis, converting it into chemical energy. Herbivores feed on plants. Carnivores feed on herbivores. Decomposers—fungi and bacteria—break down dead matter, releasing nutrients back into the soil. It’s a never-ending loop, a cycle that powers life across the globe.

Though each ecosystem may appear unique—swamps, tundras, coral reefs—they all share this fundamental cycle: energy flow and nutrient cycling. And within that framework, countless variations emerge, sculpted by climate, geography, and evolutionary history.

Forests: The Lungs and Libraries of the Earth

Forests are the most iconic of ecosystems—lush, mysterious, and teeming with life. Tropical rainforests, like those in the Amazon, contain more biodiversity than any other terrestrial ecosystem. A single hectare might house hundreds of tree species and thousands of insects.

Yet forests are not just biodiversity vaults. They are vast carbon sinks. Through photosynthesis, trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in trunks, roots, and soils. This process moderates Earth’s climate, slowing the buildup of greenhouse gases.

The complex vertical layering of forests—from canopy to understory to forest floor—creates micro-habitats, allowing species to specialize and thrive. Sloths hang from high branches, while leafcutter ants farm fungi underground. Predators like jaguars or wolves shape populations, while fungi silently knit tree roots together through mycorrhizal networks—an underground communication system sometimes dubbed the “wood wide web.”

But forests are also vulnerable. Logging, agriculture, and urbanization continue to strip away trees at alarming rates. Deforestation not only releases stored carbon but fractures ecosystems, often beyond repair.

Oceans: The Planet’s Silent Powerhouse

Covering over 70% of Earth’s surface, oceans are not just vast bodies of water—they are dynamic ecosystems teeming with life from surface to seafloor.

The upper sunlit zone, or photic zone, supports plankton—tiny organisms that form the base of the marine food web. Phytoplankton, the plant-like version, perform photosynthesis and produce more than half of the world’s oxygen. Without them, our atmosphere—and our lungs—would be in trouble.

Marine ecosystems are incredibly diverse: coral reefs, kelp forests, open ocean gyres, hydrothermal vents. Coral reefs, though occupying less than 1% of the ocean floor, support over 25% of all marine species. Their complex calcium carbonate structures provide shelter and feeding grounds for fish, mollusks, crustaceans, and even sharks.

Far below, in the lightless abyss, life thrives near hydrothermal vents. Here, organisms survive not on sunlight but on chemosynthesis—using chemicals like hydrogen sulfide to power life. Tube worms, blind shrimp, and extremophile bacteria form miniature ecosystems alien to most of the planet’s surface dwellers.

Overfishing, ocean acidification, and warming seas now threaten marine ecosystems. Coral bleaching, rising sea levels, and disrupted migration patterns signal a system out of balance.

Grasslands: The Underappreciated Breadbaskets

Often overshadowed by forests and oceans, grasslands cover nearly a third of Earth’s land area. These open, sun-drenched ecosystems support vast herds of herbivores—zebras in the African savanna, bison on the North American prairie—and the predators that follow them.

Grasslands are shaped by fire and grazing. Regular burning, whether natural or managed, prevents tree encroachment and recycles nutrients. Grazers keep plant growth in check, enabling a dynamic mosaic of habitats.

The soil beneath grasslands is among the most fertile in the world, leading to heavy conversion to farmland. While this makes them vital for food production, it also means grasslands are among the most endangered ecosystems. In the U.S., over 90% of native tallgrass prairie has been lost.

Restoring grasslands involves reintroducing native species, controlling invasive plants, and sometimes mimicking natural fires. Their conservation is key not only for biodiversity but for sustainable agriculture and carbon storage.

Deserts: Sparse Yet Spectacular

Deserts may seem barren, but they are ecosystems of astonishing resilience. Adaptation is the name of the game here. Plants like cacti conserve water through thick skins and reduced leaves. Animals—foxes, snakes, scorpions—burrow during the day and emerge at night, avoiding the sun’s wrath.

These systems respond dramatically to rain. A brief storm can trigger a wildflower bloom, turning dusty expanses into carpets of color. Insects emerge, birds arrive, and predators stir.

Life in deserts operates on razor-thin margins. Water is the limiting factor, shaping every form of life. Yet deserts also remind us that nature thrives on ingenuity. The mere existence of organisms in such extremes is a testament to evolution’s power.

Human activity—particularly groundwater extraction and development—threatens these fragile systems. Protecting deserts means respecting their rhythm, not trying to force our own upon them.

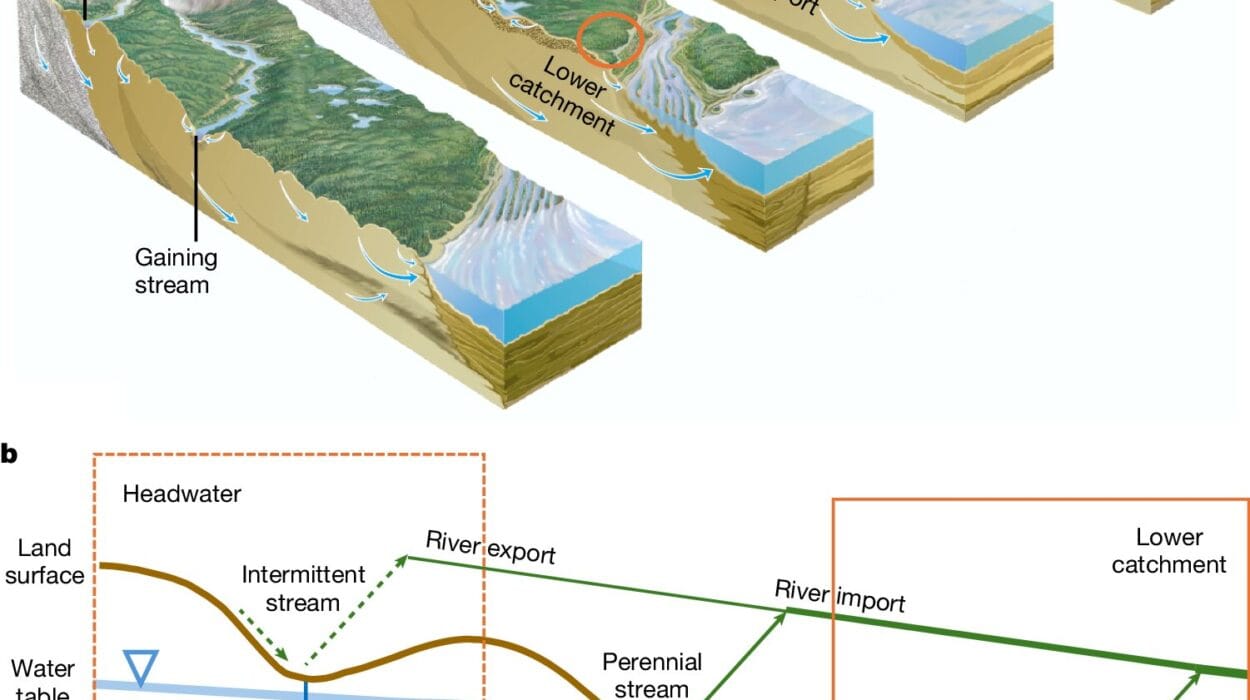

Wetlands: Nature’s Filters and Floodguards

Marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens—wetlands are the unsung heroes of the ecosystem world. They act as sponges, absorbing excess rain and reducing the risk of floods. They filter pollutants from water, protecting downstream ecosystems and human communities.

Biologically, they’re hotbeds of activity. Amphibians, birds, fish, and invertebrates rely on wetlands to breed and feed. Many migratory birds use them as seasonal pit stops.

Yet wetlands have suffered some of the greatest losses. Over half of the world’s wetlands have been drained for development or agriculture. Their restoration offers one of the best returns on investment for both biodiversity and climate resilience.

The Microbial World: Invisible, Indispensable

Beneath the soil, inside your gut, in every drop of water—microbes rule. These single-celled organisms are the engines of decomposition, nitrogen cycling, fermentation, and even disease resistance.

Soil ecosystems in particular depend on bacteria and fungi to break down organic matter, making nutrients available to plants. The rhizosphere—the narrow region around plant roots—is a bustling zone of microbial trade, negotiation, and warfare.

In oceans, cyanobacteria and other microbes drive carbon and nitrogen cycles. In extreme environments like hot springs or acidic lakes, archaea and extremophiles challenge our definitions of life.

Human medicine and agriculture have only begun to appreciate the vast influence of microbial ecosystems. From probiotic foods to regenerative soil practices, the invisible world is finally getting the attention it deserves.

The Human Factor: Interference and Integration

Humans are not separate from ecosystems—we are embedded in them. Yet our actions often disrupt more than they sustain.

Urbanization replaces complex habitats with concrete. Industrial agriculture simplifies landscapes, reducing biodiversity. Emissions from fossil fuels change the climate, pushing ecosystems toward thresholds they may not recover from.

And yet, humans are also uniquely capable of ecosystem stewardship. Indigenous cultures have long practiced sustainable interaction with land and wildlife. Modern science now confirms what many traditional practices already knew: balance is possible.

Efforts like rewilding, ecological restoration, sustainable agriculture, and conservation technology aim to harmonize human development with ecological health. The concept of “ecosystem services”—clean air, water, pollination, climate regulation—underscores that what benefits ecosystems benefits us.

Ecosystems in Crisis: Tipping Points and Resilience

The Anthropocene—the current era shaped by human activity—has brought ecosystems to a critical point. Coral reefs are dying, rainforests are shrinking, and species are vanishing at rates not seen since the last mass extinction.

Yet ecosystems can be remarkably resilient—if the damage doesn’t exceed a tipping point. Beyond certain thresholds, feedback loops kick in. A forest, once cleared, might not return. A dying coral reef can become a graveyard of algae-covered rubble.

But hopeful stories exist. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone revitalized entire landscapes. Dam removals have allowed fish to reclaim ancestral spawning grounds. Reforestation projects are turning barren hills green again.

Understanding the interconnectedness of ecosystems gives us a powerful lens: it shows us that damage anywhere ripples everywhere—but so does restoration.

Living as Part of the Web

To explore ecosystems is to rediscover our place in the web of life. Not as rulers above it, not as mere observers outside it, but as participants within it. Every breath we take is filtered by plants. Every meal is built from a food web. Every glass of water has passed through soil, root, and sky.

In ecosystems, we find not only the beauty of diversity but the wisdom of connection. Predators shape prey behavior. Soil microbes influence forest health. Bees link flowers to fruit. Every thread, no matter how small, matters.

As the climate changes and the pressures mount, our survival will not come from escaping nature—but from embracing it. From restoring what we’ve broken. From learning to live in relationship, not domination.

Ecosystems are not just “out there” in national parks or distant jungles. They are in cities, in backyards, even in the bodies we inhabit. Exploring them is not merely a scientific pursuit—it’s an act of reconnection, a return to the truth that life on Earth is not a collection of separate species but a single, breathing, evolving whole.

And in that whole, every part—every coral, every tree, every beetle, every bacterium—has a role to play. Including us.