The Earth’s surface, once thought to be a stable cradle for human life, is now increasingly unpredictable. Rising global temperatures, extreme weather events, desertification, and flooding are no longer distant warnings—they are the lived reality of millions around the globe. Wildfires consume forests, hurricanes batter coastal cities, and prolonged heatwaves challenge the very limits of human physiology. In such a scenario, the question arises: could humans retreat below the Earth’s surface to survive a planet that is slowly becoming inhospitable? The idea is no longer the realm of science fiction; it is a scientific and sociological proposition that demands careful consideration.

The notion of underground living is not new. Throughout history, humans have sought refuge beneath the surface. Ancient civilizations, from the underground cities of Cappadocia in Turkey to the troglodyte dwellings of North Africa, utilized subterranean spaces to escape harsh climates or invading forces. Modern engineering and materials science now open the possibility of extending these ancient principles to create habitable, self-sufficient underground cities capable of sustaining human life in an era of climate extremes.

Subterranean Spaces: A Natural Shelter

Earth itself provides remarkable insulation. The deeper one goes, the more constant the temperature becomes. Even a few meters below the surface, temperature fluctuations caused by day and night cycles or seasonal changes are minimal. At greater depths, the thermal stability is profound. In theory, a network of subterranean habitats could protect humans from heatwaves, hurricanes, freezing winters, and even the ultraviolet radiation that increasingly penetrates a warming atmosphere.

Yet the allure of underground living is tempered by the realities of physics and biology. Humans evolved under the open sky, bathed in natural light, and attuned to circadian rhythms regulated by the sun. Removing ourselves from that environment has profound implications for both mental and physical health. Research in cave studies, long-duration space missions, and polar expeditions provides insights: prolonged lack of natural light can disrupt hormonal balance, impair sleep, and even contribute to psychological disorders. Therefore, any plan for subterranean survival must account for artificial light cycles, psychological well-being, and the recreation of the sensory experiences that sustain human life above ground.

Engineering the Underground Environment

Constructing viable subterranean habitats requires advanced engineering. The first challenge is structural integrity. The deeper humans go, the greater the pressure exerted by overlying soil and rock. Tunnels and chambers must be reinforced with high-strength materials, resilient to seismic activity, flooding, and long-term erosion. Modern techniques, including shotcrete linings, steel reinforcement, and geopolymers, offer viable solutions, but costs are substantial.

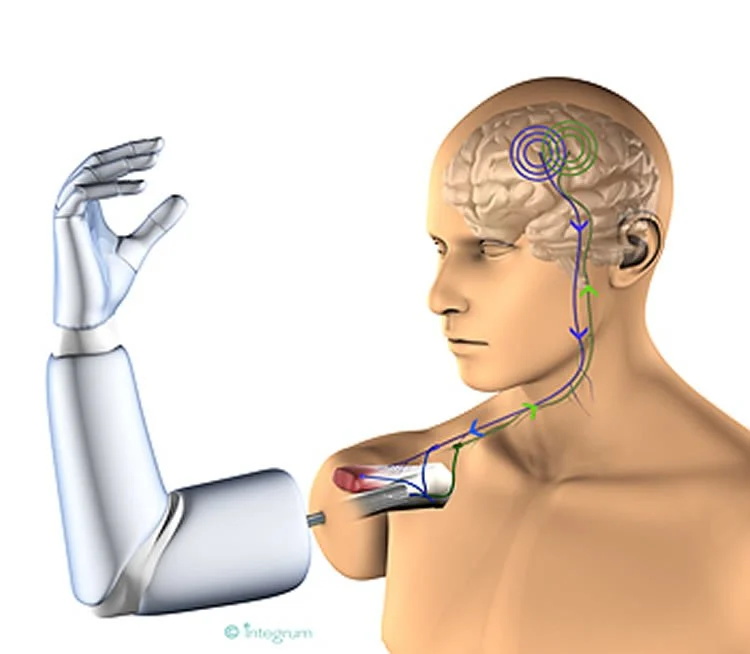

Ventilation and air quality present another set of challenges. Subsurface spaces naturally lack airflow. Humans exhale carbon dioxide, and without proper circulation, levels can rise to dangerous thresholds. Engineering systems must provide continuous oxygen replenishment, filtration of pollutants, and regulation of humidity. Advanced life-support systems, inspired by space habitats on the International Space Station, can recycle air and water, but maintaining redundancy and reliability in large-scale habitats remains a formidable hurdle.

Energy is the lifeblood of underground living. Solar energy is less accessible, and traditional wind or hydroelectric power may be limited by location. Some proposals suggest harnessing geothermal energy, which increases with depth, or installing nuclear reactors for continuous power. These solutions are feasible but come with their own risks and ethical considerations, especially in densely populated underground communities.

Water management is equally critical. Subterranean habitats would need self-contained systems for water collection, purification, and recycling. Rainwater capture from the surface, filtration of groundwater, and closed-loop water systems could sustain communities, but contamination or system failure could be catastrophic. Waste management, including recycling of organic matter and human excrement, must be carefully engineered to prevent disease outbreaks.

Psychological and Social Dimensions

Survival underground is not merely a technical problem—it is profoundly human. Humans are social creatures, and confinement in enclosed spaces can amplify stress, anxiety, and interpersonal tension. Experiences from submariners, astronauts, and miners reveal that long-term isolation or lack of natural environmental cues can lead to depression, aggression, and cognitive decline.

To address these concerns, designers of underground habitats must incorporate spacious layouts, access to artificial or simulated nature, communal areas, and cultural activities. Light therapy, artificial skylights, and biophilic design—integrating natural patterns, vegetation, and water features—can alleviate psychological stress. Maintaining social cohesion is as critical as sustaining air, water, and food. Without careful attention to human behavior, an underground city could survive physically but fail socially.

Food and Sustainability

Sustaining human life underground necessitates robust agricultural solutions. Traditional farming requires sunlight, soil, and space—resources limited below ground. Hydroponics and aeroponics, where plants grow in nutrient-rich water or mist without soil, offer promising alternatives. LED lighting can simulate sunlight, and controlled climate conditions can optimize growth cycles. However, producing enough calories and nutrients for large populations is a complex challenge. Protein sources, often requiring larger space or specialized systems, must be carefully integrated, whether through insect farming, lab-grown meat, or aquaculture systems.

Moreover, the closed-loop ecosystem must balance carbon dioxide from humans with oxygen produced by plants. This requires precise monitoring and adjustments to prevent ecological collapse within the habitat. The complexity of these systems mirrors those designed for space colonies on Mars or the Moon, highlighting that underground living, while protective against climate extremes, is an ambitious and delicate endeavor.

Lessons from Extreme Environments

Several human experiments provide insight into long-term subterranean survival. The Biosphere 2 project in Arizona, a sealed ecological system, demonstrated both the potential and fragility of closed ecosystems. Oxygen depletion, unexpected chemical reactions in soil, and social conflicts among participants illustrated the intricate interplay of biology, engineering, and psychology.

Similarly, Arctic research stations, Antarctic bases, and submarine deployments offer data on living in isolation and extreme conditions. These experiences underscore the importance of redundancy, adaptability, and psychological resilience. They also reveal that humans are remarkably adaptable, capable of finding community, purpose, and even joy in environments far removed from the natural world.

Climate Change and the Underground Imperative

The urgency of climate change intensifies the attractiveness of subterranean solutions. Projections suggest that by the end of the century, vast regions could experience temperatures beyond human tolerance, water scarcity could threaten agriculture, and storms could devastate infrastructure. Retreating underground offers a controlled environment, shielded from atmospheric instability and surface hazards.

Yet underground living is not a panacea. It requires massive investment, careful planning, and ongoing maintenance. It does not address the root causes of climate change—greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and unsustainable industrial practices. In a sense, underground survival is a last-resort strategy, akin to building an ark in anticipation of a flood. It buys time, protects lives, and preserves knowledge, but it cannot replace efforts to restore balance to the Earth’s climate system.

The Future of Subterranean Civilizations

Envisioning the future, underground cities could range from temporary refuges during heatwaves to permanent habitats shielding entire populations. Advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, and nanotechnology may facilitate construction, maintenance, and resource management. Networks of sensors could monitor structural integrity, air quality, and ecological balance in real time, while automated systems maintain life-support functions with minimal human intervention.

Culturally, underground living could redefine human identity. Architecture, art, and community organization might evolve in response to confined spaces, creating unique expressions of creativity. Social norms, family structures, and educational systems could adapt to the subterranean context. In this vision, humans are not merely surviving; they are building a new form of civilization, one that harmonizes with the protective embrace of the Earth itself.

Ethical and Philosophical Considerations

Living underground raises profound questions about human values and priorities. Who decides who gets access to these shelters? How do we balance individual freedom with communal safety? Could life underground become elitist, reserved for those who can afford protection, while others face the ravages of climate change above?

Philosophically, retreating below the surface challenges our relationship with nature. Humans have always sought to shape and dominate their environment, but underground living is a surrender in some sense—a recognition that the surface world may no longer be hospitable. It forces a reflection on stewardship, responsibility, and the consequences of collective action.

Conclusion: Humanity Below the Surface

The possibility of humans living underground to survive climate change is no longer purely speculative. It is grounded in science, engineering, psychology, and ecology. While the challenges are immense, so too are the opportunities. Subterranean living could preserve human life, culture, and knowledge in the face of environmental extremes. It could inspire innovations in energy, agriculture, architecture, and social organization.

Yet it is a strategy of necessity, not preference. The ultimate goal remains restoring balance to the Earth’s climate, reducing emissions, and protecting the natural systems that sustain life. Underground habitats offer refuge, not redemption. They are a testament to human ingenuity, adaptability, and resilience—a reminder that even as the surface becomes uncertain, humans possess the imagination to survive, adapt, and thrive in unexpected places.

In the end, subterranean life is more than a survival mechanism. It is a reflection of human tenacity, a vision of hope, and a challenge to redefine our relationship with the planet. As climate change accelerates, the question is no longer whether humans can live underground—it is whether we are willing to embrace the profound transformations required to do so, and whether we can do it in harmony with the fragile world above.