For thousands of years, the people of China have honored their dead with remarkable care, building elaborate tombs that mirror their beliefs about life, death, and eternity. A new study published in PLOS One by Quanbao Ma and colleagues at the Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture reveals that these tombs, scattered across the vast landscape of China, are not just silent resting places. They are historical records, tracing how geography, politics, and prosperity shaped Chinese civilization from its earliest dynasties to modern times.

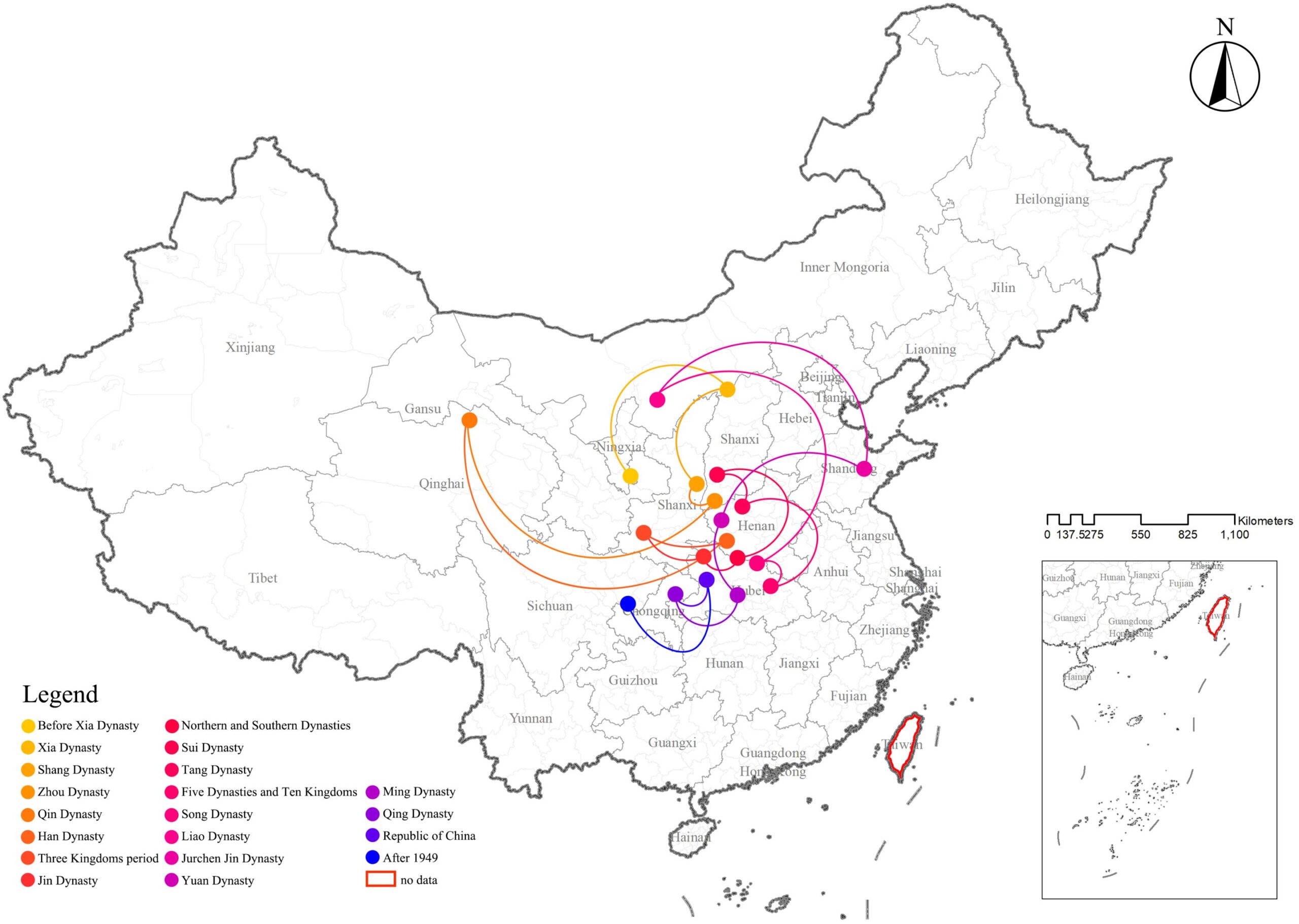

The research team created a digital map of tombs spanning roughly four millennia—from the legendary Xia Dynasty, more than 4,000 years ago, to the recent centuries. Their goal was to uncover the hidden patterns in how, when, and where people buried their dead. What emerged was a striking reflection of China’s ever-changing fortunes: times of peace and wealth left behind monumental resting places, while eras of chaos and war were often too unstable to do the same.

The Silent Record of Stability and Chaos

Each tomb is a story about the living as much as the dead. The study found that many of China’s surviving ancient tombs belong to periods of political and economic stability, such as the Qin-Han and Yuan-Ming-Qing dynasties. These eras allowed people to invest energy, resources, and artistry into their beliefs about the afterlife. When the nation prospered, so did its tombs.

In contrast, periods of unrest—like the Five Dynasties era, marked by civil war and rapid dynastic turnover—left behind fewer tombs. When the living were preoccupied with survival, they had little capacity to construct enduring monuments for the dead. The gaps in China’s archaeological record are therefore not accidents of time; they are scars left by centuries of turmoil.

The researchers interpret this pattern as an echo of human priorities. When people are secure and thriving, they look beyond the immediate needs of life toward continuity and remembrance. When life is fragile, the future shrinks to the present moment, and the luxury of an elaborate burial fades away.

Movement of People, Movement of Tombs

The study also reveals how migration shaped the geography of ancient burial sites. From the late Eastern Han dynasty through the Northern and Southern dynasties, war repeatedly swept across northern China. Families fled southward, carrying their customs and traditions with them. Tombs from this turbulent period are therefore concentrated in the southern regions, mirroring the movement of entire populations.

Burial patterns thus form a kind of shadow history of China’s demographic shifts. As people moved to escape conflict or seek fertile land, they re-rooted their traditions in new soil. The resting places they built became markers of both displacement and endurance, recording the migrations that political records often obscure.

Landscapes That Protect Memory

Geography played a crucial role not only in where people chose to build tombs but also in which ones have survived to the present day. The study found that the Chengdu-Chongqing region and the Central Plains stand out for their high density of preserved tombs.

These regions share several advantages. Both have vast stretches of flat land suitable for settlement, fertile soil for agriculture, and abundant water resources that sustained large populations. Such environmental richness encouraged long-term habitation — and with it, the construction of more permanent burial sites.

Humidity also played a surprising role. The relatively moist climates of these regions helped preserve the materials placed inside the tombs. Objects made of wood, fabric, or lacquer, which might have decayed elsewhere, survived for centuries underground. The soil itself became a gentle archivist, protecting the artifacts of belief, power, and daily life.

The Central Plains, in particular, have long been regarded as the cradle of Chinese civilization. The concentration of tombs there is a testament to its enduring importance as a political, cultural, and agricultural heartland. To walk across its fields today is to walk over layers of history — the buried memory of dynasties, emperors, farmers, and poets.

What Tombs Teach About the Living

Beyond their archaeological and artistic value, these tombs are windows into how ancient Chinese people understood life and death. They reveal changing ideas about the soul, the afterlife, and the relationship between the living and the dead. A grand tomb might symbolize the authority of an emperor, but it also reflects the hopes of a society that believed the world of spirits was a continuation of earthly existence.

When the economy flourished and people enjoyed stability, tombs became more elaborate. They included chambers, murals, and offerings meant to provide comfort in the afterlife. The materials — jade for purity, bronze for power, silk for refinement — were chosen not only for beauty but for spiritual significance.

In times of hardship, however, tombs grew simpler. The objects buried with the dead reflected necessity rather than aspiration. The grandeur of the afterlife was a luxury of the prosperous. Thus, tombs record not only the changing styles of craftsmanship but the emotional and spiritual fluctuations of entire societies.

Technology Meets Tradition

What makes this new study remarkable is its use of digital mapping and spatial analysis. By systematically cataloging tombs across thousands of years and vast regions, the researchers could visualize patterns that no single excavation could reveal. The map became a kind of time machine, showing how burial traditions evolved in response to human movement, political order, and environmental change.

This digital approach also lays the foundation for future preservation efforts. Many ancient tombs are threatened by erosion, construction, and urban expansion. Understanding where they are and why they were built in those locations helps archaeologists and governments decide how best to protect them. The researchers hope their findings will contribute to a “scientific and precise protection system” — a framework that treats each tomb not as an isolated artifact but as part of a living landscape of cultural memory.

Preserving the Past for the Future

Every tomb represents a dialogue between the past and the present. The builders sought permanence, yet they could not imagine that millennia later, their resting places would become data points in digital maps, studied by satellites and scholars. What endures is not only the stone and soil but the human impulse to remember and to be remembered.

Quanbao Ma and his team remind us that tombs are not just archaeological curiosities. They are evidence of resilience — proof that even in the face of impermanence, people have always sought to anchor their identities in something lasting. By studying the spatial and temporal distribution of these ancient sites, we learn how geography shapes culture and how stability shapes memory.

The tombs of China are therefore not silent at all. They speak, through the patterns of their distribution and the treasures they protect, of the dreams and anxieties of generations long gone. They tell us that civilization is more than the story of rulers and wars — it is also the story of ordinary people who, in life and in death, built monuments to hope.

The Eternal Conversation Between Earth and Memory

As China continues to modernize, skyscrapers rise where emperors once ruled, and highways cross landscapes once sacred to the dead. Yet beneath the surface, the tombs remain — markers of a continuity deeper than any dynasty. The study in PLOS One shows that the geography of memory is as important as the geography of land. It reminds us that to preserve tombs is to preserve the map of a civilization’s soul.

Each mound, each chamber, each forgotten inscription adds to the chorus of voices that form China’s vast historical symphony. And if we listen carefully, the message is timeless: that the measure of a culture lies not only in how it lives, but in how it remembers.

More information: The spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and influencing factors of ancient tombs in China: A study on the conservation of ancient tombs in China, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0333485