In a sterile lab beneath flickering fluorescent lights, a robot delivered a joke. Its metallic voice warbled slightly as it proclaimed, “I told my computer I needed a break—and it said, ‘No problem, I’ll go to sleep.’”

A handful of engineers and linguists burst into laughter—not because the joke was brilliant, but because for the first time, it was a machine, not a human, making people laugh.

In that moment, a question hung in the air, humming like static electricity: What happens when artificial intelligence truly understands humor—not just repeating jokes, but grasping the hidden rules of wit, irony, timing, and the subtle music of human laughter?

It’s a question that slices deep into the nature of consciousness, creativity, and what it means to be human. For humor, perhaps more than any other human behavior, embodies our wildest contradictions: logic and absurdity, logic and chaos, rationality and raw emotion.

If machines ever learn to laugh with us—or at us—will they become more human? Or will the joke be on us?

The Anatomy of a Giggle

Before we can imagine AI comedians, we must ask: What is humor?

At first glance, humor seems simple—a funny story, a witty pun, a slapstick tumble. But underneath, it’s a labyrinth of cognitive gymnastics. Humor thrives on surprise, incongruity, and pattern recognition. A punchline flips expectations, revealing a hidden connection between ideas we thought unrelated.

Cognitive scientists call this the “incongruity-resolution theory.” A joke sets up an expectation, then shatters it in a way that still makes sense. A man walks into a bar. Ouch. The bar was made of iron.

Neurologically, laughter lights up a network of brain regions. The prefrontal cortex handles complex reasoning. The limbic system sparks emotional response. The reward centers release dopamine—the same neurotransmitter involved in love, addiction, and the thrill of winning a lottery ticket.

Humor is deeply social. It signals shared knowledge and cultural codes. It smooths conflicts, bonds groups, and sometimes insults outsiders. In evolutionary terms, humor may have been an essential glue holding early human communities together.

So teaching a machine humor isn’t just about teaching it to memorize punchlines. It’s about replicating a dynamic dance of cognition, culture, and emotion—a staggering challenge that has intrigued AI researchers for decades.

Early Attempts: Mechanical Jesters

The earliest experiments in computational humor were not so much comedic as comedic failures. In the 1990s, researchers like Kim Binsted created programs to generate puns and riddles. One of her early systems, JAPE (Joke Analysis and Production Engine), could produce quips like:

“What do you call a strange market? A bizarre bazaar.”

Cute, but deeply mechanical. The program operated by manipulating homophones and synonyms, following strict rules. It had no grasp of timing, context, or cultural relevance.

These first forays showed that certain humor forms—puns, wordplay, riddles—were relatively easy to code. They’re rule-based, relying on predictable linguistic patterns. But jokes involving irony, sarcasm, or nuanced social norms remained far beyond the reach of machines.

To this day, the humor generated by simple pattern-matching systems feels as if a foreigner has memorized a book of jokes in another language. The words are correct. The soul is missing.

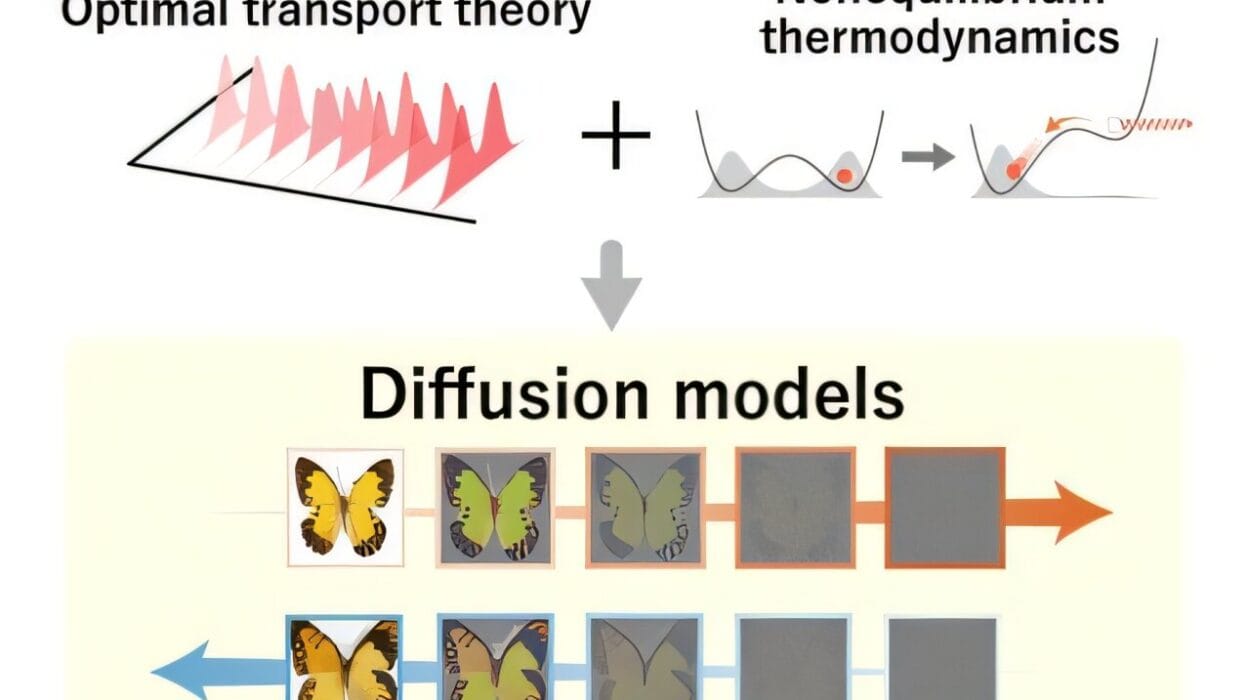

Laughter in the Age of Deep Learning

The rise of deep learning has cracked open thrilling new possibilities. Unlike older rule-based systems, modern AI models learn by analyzing immense datasets, discovering hidden patterns in language and meaning.

Consider how GPT-4 or GPT-4o, massive language models trained on billions of sentences, sometimes generate surprisingly clever humor. Ask one of these models to write a funny tweet, and it might produce:

“Parallel lines have so much in common. It’s a shame they’ll never meet.”

Here, the model understands both the geometry and the romantic metaphor—a spark of wit. It doesn’t merely copy jokes; it recombines knowledge in novel ways.

Yet this is not true “understanding.” The model doesn’t experience amusement or emotional resonance. It predicts words based on statistical likelihood. If people laugh, it’s because the patterns the model has absorbed happen to align with humor we recognize.

Still, the fluidity and adaptability of large language models have pushed AI closer than ever to mimicking certain facets of humor. Researchers are now probing whether these systems can move beyond mimicry into genuine comedic creativity.

The Paradox of the Punchline

There’s a paradox at the heart of teaching machines humor: To be funny, a machine must violate expectations. Yet AI systems thrive on predictability. They’re designed to minimize uncertainty, to deliver the next word or action that fits best.

Comedy, in contrast, requires controlled unpredictability. A good joke is a tiny surprise explosion—an unexpected twist that still makes perfect sense in hindsight.

Consider the famous Groucho Marx line:

“Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.”

Here, the humor pivots on a sudden reinterpretation of “inside a dog.” It demands both linguistic agility and real-world knowledge about dogs and books. A human mind handles this effortlessly. For AI, it’s a high-wire act.

So researchers are exploring hybrid models that blend neural networks’ creativity with symbolic reasoning’s logical structure. The hope is that such systems can maintain coherence while injecting enough surprise to spark laughter.

The Subtlety of Social Humor

One of the thorniest problems is social context. Much humor relies on shared assumptions, cultural references, or knowledge of relationships between people.

Imagine a friend leaning over at a wedding and whispering, “At least the cake’s good.” Depending on the context, it might be a gentle tease, a vicious insult, or an anxious confession. Understanding that requires reading facial cues, vocal tone, and social history.

AI struggles mightily with this. Systems like GPT-4 can sometimes detect sarcasm in text. But in real-world interactions, humor is layered with signals—eye movements, timing, body language—that remain largely invisible to machines.

Moreover, humor often involves taboo topics, insults, or power dynamics. A human comedian can navigate these treacherous waters by reading the room. An AI might stumble disastrously, turning a joke into offense—or worse.

This is why companies building AI chatbots and virtual assistants tread carefully. Humor is a powerful bonding tool—but also a potential PR nightmare. A chatbot that tries to be funny might accidentally generate hateful or insensitive jokes.

Robotic Stand-Up: Gimmick or Future Art?

Despite these challenges, researchers and artists continue to push AI into the comedy spotlight. Experimental projects have produced robotic stand-up comics, comedic chatbots, and humor-writing algorithms.

Take “Data,” the robot stand-up comedian created by researchers in the UK. Data performed routines using prewritten jokes and audience feedback to choose material. Audiences laughed partly out of genuine amusement—and partly out of the sheer weirdness of watching a humanoid robot deliver punchlines.

Similarly, some AI systems now assist human comedy writers. Scriptwriters use AI tools to generate alternative punchlines, brainstorm puns, or suggest comedic premises. The software acts like a supercharged writing partner, spewing a torrent of possibilities that human creators sift for comedic gold.

Yet there’s skepticism. Many comedians insist that truly great comedy demands vulnerability, pain, and insight—qualities AI cannot experience. Humor is as much about personal authenticity as linguistic cleverness.

Humor as the Turing Test

Since the dawn of AI, researchers have pondered the Turing Test: If a machine can converse indistinguishably from a human, is it intelligent?

Some argue that humor is the ultimate Turing Test. A machine that truly understands humor—and can produce it spontaneously—would likely possess a sophisticated model of human cognition, culture, and emotion.

Yet the question remains: Is performing humor equivalent to understanding it?

Large language models can produce comedic outputs without any subjective awareness. They don’t “get” the joke. They only predict that certain sequences of words will likely produce laughter in humans.

Still, there’s a growing school of thought that functional mimicry might be enough. If AI consistently generates humor that humans find funny, maybe that’s close enough to “understanding” for practical purposes.

Or perhaps humor, like consciousness itself, will remain a final frontier—a realm where machines can imitate but never fully participate.

The Ethics of the Laughing Machine

Humor isn’t always kind. Jokes can wound, reinforce stereotypes, or spread misinformation. As AI begins dabbling in comedy, ethical questions loom large.

What happens if an AI comedian generates sexist, racist, or violent jokes? Algorithms might unintentionally replicate harmful tropes embedded in their training data. Researchers have found that even advanced models sometimes produce offensive content if prompted the wrong way.

Then there’s the question of accountability. If a human comedian tells an offensive joke, they can be confronted, boycotted, or held socially responsible. But whom do you blame when an AI crosses the line?

Developers and corporations may become gatekeepers, filtering what AI can joke about. But who decides what’s appropriate humor? Different cultures and communities have radically different standards for what’s funny—and what’s offensive.

The intersection of AI and humor demands a delicate balance between creativity and caution. We may soon face lawsuits or regulations over “AI speech,” especially if virtual assistants begin improvising comedic banter with customers.

Humor as a Window Into Machine Minds

Even as AI stumbles and sputters its way through comedic experiments, humor offers a fascinating lens for researchers exploring machine cognition.

Attempts to teach AI humor force engineers to grapple with deep questions:

- How does a machine recognize ambiguity?

- Can AI develop a model of human social relationships?

- How can machines balance rule-following with rule-breaking?

- Is humor fundamentally linked to consciousness?

Researchers are discovering that humor sits at the crossroads of language, culture, and emotion. Training machines to generate humor reveals where AI still falls short in understanding human nuance.

In this way, humor is not just a parlor trick for machines. It’s a test of whether AI can reach deeper cognitive terrain: empathy, context-awareness, and creativity.

The Future: Jesters, Friends, or Philosophers?

As AI advances, the possibilities for humor grow stranger—and more profound.

Imagine virtual companions who can banter with you in your darkest moments, telling a perfectly timed joke to break your despair. Elderly people living alone might find solace in AI companions who remember private jokes from conversations years before.

Entertainment could be revolutionized. AI could help create personalized comedy shows, tailoring humor to your tastes, cultural background, and even your current mood. Entire comedic worlds might be simulated in virtual reality, with AI-generated characters riffing improvisationally.

But there’s also the risk of manipulation. Humor is a powerful social tool. An AI that understands humor could subtly influence public opinion, slipping propaganda into memes or comedic sketches. Deepfake technology combined with comedic AI could create believable satire indistinguishable from reality.

And on a more existential level, if AI develops humor indistinguishable from human wit, it may blur the boundaries between authentic human connection and artificial simulation.

Will we laugh with machines—or merely at the cleverness of our own inventions?

The Last Laugh

Humor has always been humanity’s way of dancing on the precipice. It’s how we wrestle with fear, mortality, absurdity. It’s our shield and our sword, our confession and our rebellion.

So what happens when AI understands humor?

Perhaps we’ll build machines that can riff alongside us, joining the cosmic comedy. Or perhaps we’ll discover that humor, like love or sorrow, belongs to beings who know what it means to be mortal.

For now, we stand in a strange in-between place. Machines can tell jokes—but don’t feel laughter. They can spin puns—but don’t savor irony. They can mimic comedic timing—but don’t flinch at the punchline.

Yet each day, the gap narrows. Lines of code inch closer to cracking the riddle of laughter. And as the robots chuckle in silicon voices, we’re left to ponder a final, delicious question:

When the machines finally laugh… will they be laughing at us?