On a chilly day along England’s southern coast, paleontology student Benjamin Weston crouched beside the cliffs of Durlston Bay, eyes scanning the pebbles washed up by the tide. He was searching for fragments of ancient life hidden among the shingle and sand—a pastime familiar to anyone growing up in Dorset. But what Weston plucked from the beach that day would ripple across the scientific world: a tiny, fossilized jawbone from a creature that lived alongside dinosaurs 145 million years ago.

Now named Novaculadon mirabilis, this new species reveals an astonishing tale of survival, adaptation, and the quiet drama unfolding in the shadows of giants.

An Ancient Mammal Hidden in Stone

The discovery is no less than historic. For the first time since Victorian fossil hunters prowled these cliffs, scientists have identified a new species of multituberculate mammal at Swanage—a group often nicknamed the “rodents of the Mesozoic” for their success and diversity.

Only 16.5 millimeters long, the fossil jaw is a marvel of nature’s engineering. At the front juts a sharp, pointed incisor—a tool perfect for snipping through tough vegetation or crunching insect shells. Behind it yawns a gap, followed by four razor-edged premolars, each sculpted with intricate ridges. To a casual observer, the jaw might resemble that of a rabbit. But the delicate architecture and unique arrangement of teeth unmistakably mark it as a multituberculate—a lineage that thrived for over 130 million years, coexisting with dinosaurs, and only vanishing during the Oligocene epoch some 33 million years ago.

“I instantly had my suspicions of what the jaw was when I found it at the beach, but couldn’t have imagined where the discovery would take me,” said Weston, now catapulted into the ranks of published paleontologists. “I’m extremely grateful to the team and to the university for helping me take my first steps into academic paleontology.”

Unveiling Secrets with Modern Technology

Weston’s fossil was, in many ways, still locked in stone. Fragments of rock clung stubbornly to the jaw, concealing vital details. But the University of Portsmouth’s scientists had an arsenal of modern tools at their disposal.

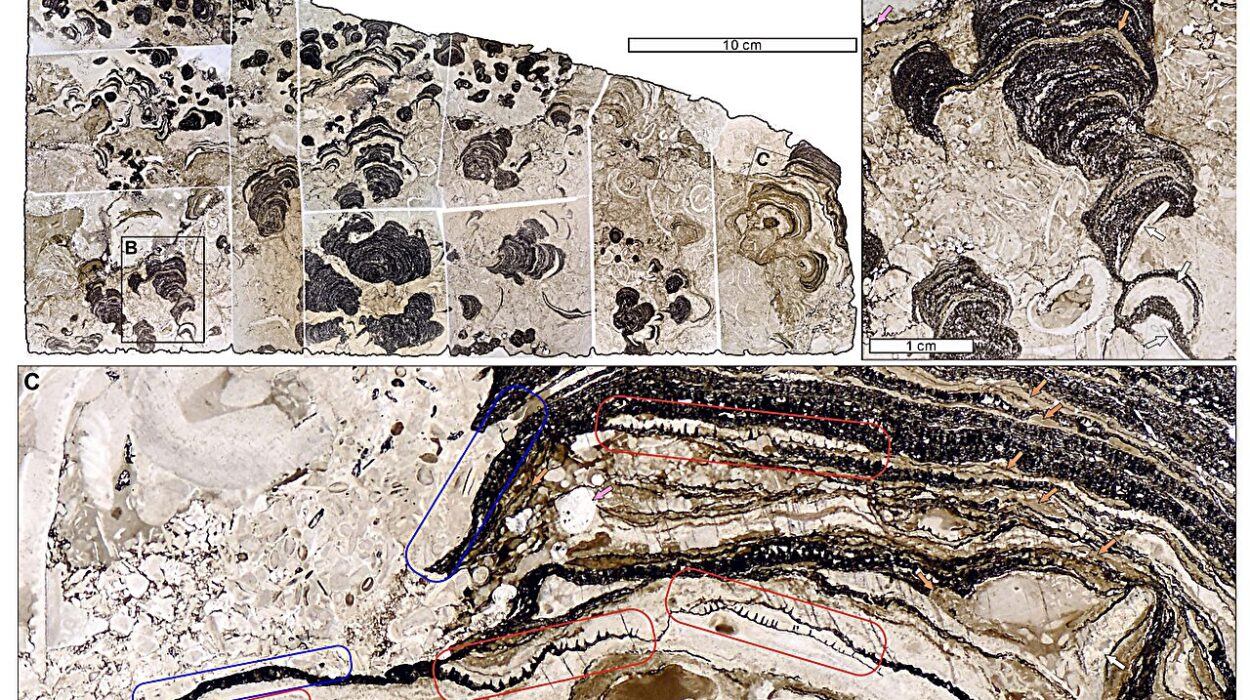

Dr. Charles Wood, senior scientific officer, employed advanced CT scanning technology to peer through the stone matrix. The high-energy X-rays revealed the fossil’s hidden structures in exquisite detail, thanks to the contrasting densities between the fossilized bone and the surrounding rock.

Enter Jake Keane, a former Portsmouth paleontology student now based in Abu Dhabi. Within hours, Keane digitally stripped away the surrounding rock from the CT scans, performing what the researchers fondly dubbed “digital dental surgery.” Each tiny tooth was isolated and reconstructed, its sharp edges and ridges made visible for the first time in 145 million years.

Armed with these digital models, lead technician John Fearnly at Portsmouth’s 3D printing lab created large-scale replicas magnified ten times. These lifelike models allowed researchers to examine the fossil’s fine details without risking damage to the fragile original.

A New Star in the Mesozoic Cast

When all the evidence came together, the fossil proved unmistakably unique. The new species was christened Novaculadon mirabilis—“novacula” meaning razor, in homage to the blade-like teeth, and “mirabilis” celebrating the miraculous preservation and discovery.

The animal is imagined as a small, furry creature, perhaps scurrying among ferns, with speculative spots and stripes. That vision comes courtesy of Portsmouth student Hamzah Imran, who painted an artistic reconstruction breathing life into this long-extinct mammal.

Unlike modern rodents, Novaculadon possessed teeth suited for an omnivorous diet. Its sharp incisors and slicing premolars suggest it fed on small invertebrates—worms, insects, and perhaps soft plant material. It lived during the Berriasian age, at the dawn of the Cretaceous, when dinosaurs like Baryonyx and Iguanodon prowled the same landscapes.

Following Footsteps of Past Discoveries

Benjamin Weston’s discovery continues a legacy of student contributions to paleontology in Dorset. In 2017, undergraduate Grant Smith uncovered fossils of two new mammal species—early ancestors of the lineage that would eventually lead to humankind. For Dr. Steve Sweetman, who advised on Weston’s fossil, it brought back memories of that earlier shock of discovery.

“This is a remarkable find that reminds me of when Grant found those extraordinary eutherian mammal teeth,” said Dr. Sweetman. “When I first saw Grant’s specimens, my jaw dropped—and I had exactly the same reaction to Ben’s multituberculate jaw. It’s incredible that Durlston Bay keeps delivering such significant mammal discoveries by our undergraduate students.”

A Testament to Teamwork and Technology

The research behind Novaculadon mirabilis was as much a human story as a scientific one. Dr. Roy Smith and Emeritus Professor David Martill guided Weston through the meticulous process of description and publication. Alumni, staff, technicians, and students all contributed skills ranging from high-resolution scanning to digital modeling and 3D printing.

“Looking back now that the discovery has been published, I am amazed at how many people it took to describe this little mammal,” said Professor Martill. “I especially appreciated that all team members were university staff or present and former students—a true team effort.”

A Living Laboratory on England’s Coast

This discovery also highlights why the University of Portsmouth’s paleontology program has become a magnet for fossil enthusiasts. Situated close to the Isle of Wight—fondly known as “Dinosaur Island”—and the fossil-rich Jurassic Coast, students enjoy unmatched opportunities to uncover the prehistoric secrets buried in local cliffs and beaches.

Field trips, hands-on excavations, and close mentoring by seasoned paleontologists have turned undergraduates into published researchers—and sometimes, into discoverers of entirely new species.

Tiny Jaw, Enormous Implications

The find of Novaculadon mirabilis does more than add a new name to the fossil record. It hints at a richer, more complex web of life during the time of dinosaurs. As Dr. Sweetman notes, these early mammals were carving out ecological niches under the feet of giants, experimenting with different diets and ways of living that would lay the groundwork for the astonishing diversity of mammals today.

For Benjamin Weston, it’s the start of what promises to be a thrilling scientific journey. And for science, it’s another reminder that even the smallest fossils can open vast new chapters in the story of life on Earth.

Reference: Benjamin T. Weston et al, A new multituberculate (Mammalia, Allotheria) from the Lulworth Formation (Cretaceous, Berriasian) of Dorset, England, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2025.101128. www.sciencedirect.com/science/ … ii/S0016787825000379