Imagine looking into the eyes of another person—someone who looks just like you, shares your DNA, your smile, even your quirks. They’re not your twin, not a sibling, and not born of natural conception. They are a clone—your biological replica, created in a lab. That possibility once seemed like science fiction. But in the age of biotechnology and genetic engineering, the once-unthinkable is now a matter of serious scientific debate. The question is no longer whether we can clone humans, but whether we should.

Human cloning raises some of the most profound questions in science, philosophy, and ethics. It intersects with ideas about identity, individuality, reproduction, and the limits of human intervention in nature. The topic compels us to ask: what does it mean to be human? Can a cloned person ever be truly free if they were created as a copy? And if science allows it, does that make it right?

This article delves deep into the science and the moral quandaries of human cloning—its promises, its perils, and the fierce debate that surrounds it in medical ethics.

Cloning 101: What Does It Actually Mean?

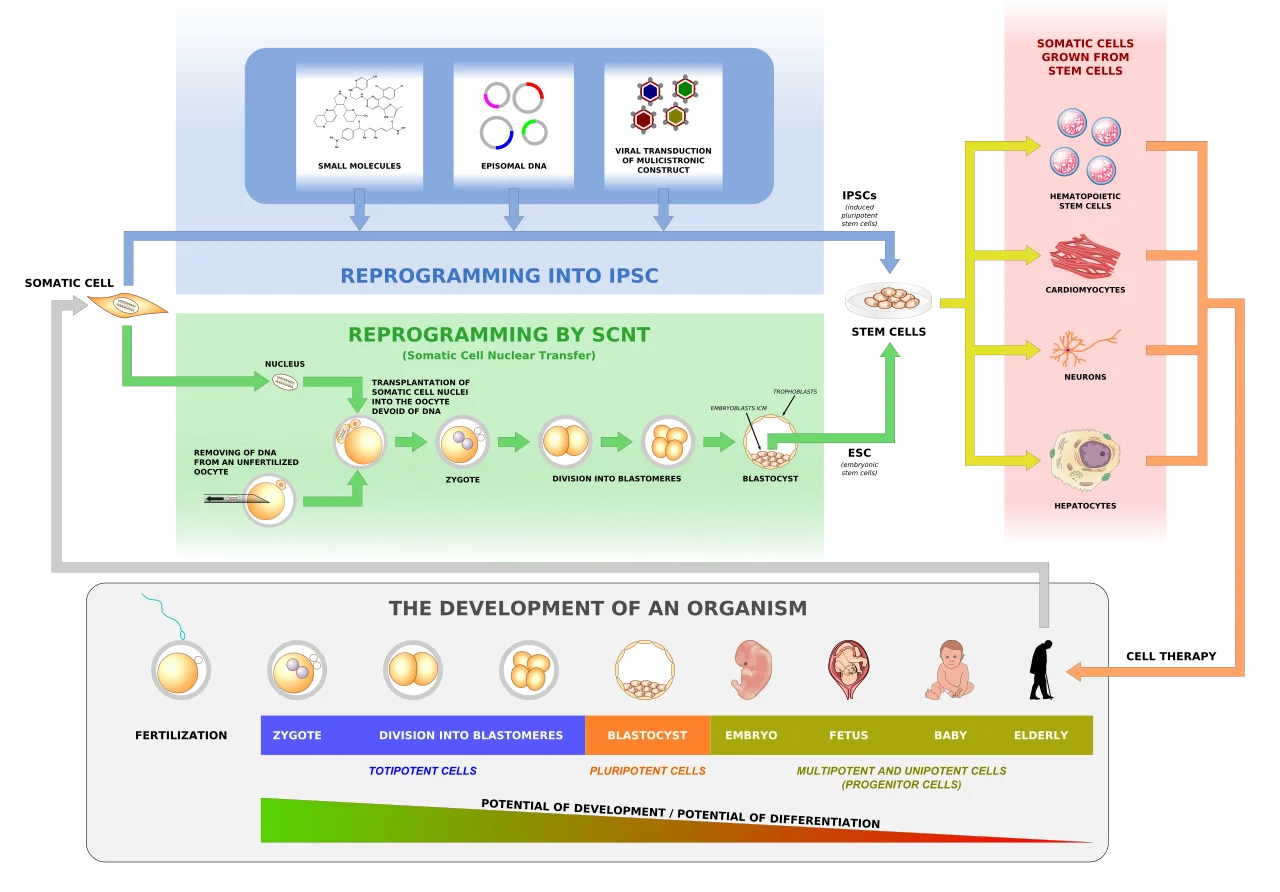

Cloning, at its core, is the process of creating a genetically identical copy of a biological entity. There are three primary types of cloning: gene cloning, reproductive cloning, and therapeutic cloning. Gene cloning deals with replicating strands of DNA. Therapeutic cloning involves creating embryos for the purpose of harvesting stem cells to treat disease. Reproductive cloning, the most controversial, involves creating a whole organism—a new lifeform, genetically identical to another.

The idea leaped into public consciousness in 1996 with the birth of Dolly the Sheep. Scientists at the Roslin Institute in Scotland successfully cloned the first mammal from an adult somatic cell, a stunning milestone that altered the trajectory of modern biology. If a sheep could be cloned, why not a human?

The answer, of course, was complex. Human biology is more intricate, and the ethical stakes far higher. Still, the door had been opened. Since then, scientists have cloned a variety of animals, from dogs to monkeys. Human embryos have been cloned for research purposes, but not brought to term—yet.

The Science Behind Human Cloning

To understand the ethical questions, one must first understand the science. The most common technique used in cloning is somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). In this method, the nucleus of a somatic cell—any cell from the body that isn’t a sperm or egg—is transferred into an egg cell that has had its nucleus removed. This egg, now containing the donor’s genetic material, is stimulated to divide and develop into an embryo. In reproductive cloning, this embryo would be implanted into a surrogate’s womb and brought to term. In therapeutic cloning, the embryo would be used to generate stem cells and then destroyed.

SCNT is incredibly difficult and inefficient. Dolly was the result of 277 attempts. Many embryos fail to develop properly, and those that do often suffer from defects or premature aging. The cloned animals that are born may exhibit abnormal size, organ dysfunction, or reduced lifespans. These scientific challenges underscore the immense risks of applying cloning to humans. Yet, with each technological advance, those barriers seem to inch closer to being surmountable.

Why Clone Humans? The Medical Arguments

One of the most compelling arguments in favor of human cloning lies in its potential medical benefits. Therapeutic cloning could lead to the development of patient-specific stem cells, used to treat conditions like Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injuries, and heart disease. Because these cells would be genetically identical to the patient’s own, the risk of rejection would be greatly reduced. Scientists envision a future where damaged organs could be replaced not with donor transplants, but with lab-grown, genetically matched tissues.

Reproductive cloning is more controversial but also comes with proposed benefits. For infertile couples, especially those who cannot produce viable sperm or eggs, cloning might offer a chance to have a biologically related child. Parents who have lost a child may hope to create a genetic replica. Some suggest that cloning could allow exceptional individuals—scientific geniuses, world-class athletes—to be “recreated” to benefit society.

But these possibilities quickly become entangled in ethical brambles. Is a clone simply a copy, or an individual in their own right? Does cloning turn children into manufactured products, rather than autonomous beings?

Identity and Individuality: The Philosophical Minefield

Perhaps the most philosophically jarring question raised by human cloning is this: what defines a person? If we create someone with the exact same DNA as another, is their identity predetermined, or can they forge their own path?

Human cloning challenges the deeply held notion that each person is genetically unique. Twins may share DNA, but their development occurs naturally and simultaneously. A clone, by contrast, would be a delayed copy. They might resemble their genetic donor, but raised in a different environment, at a different time. Would they be destined to follow the same trajectory?

Psychologists warn that cloned individuals could struggle with identity issues, constantly compared to their genetic originator. Society may project expectations onto them that they never asked for. If a clone was created to replace a lost child, would they be treated as a substitute, rather than a person in their own right? Such psychological burdens could deeply affect mental health and emotional well-being.

Moreover, the notion of uniqueness is deeply intertwined with human dignity. If we begin to mass-produce individuals with desired traits, are we turning people into commodities? This concern echoes the fears voiced in dystopian literature—from Brave New World to Gattaca—where human value is reduced to genetic pedigree.

Religious and Cultural Perspectives

Across the globe, religious traditions have offered critical perspectives on human cloning. In Christianity, particularly within Catholic and Evangelical circles, cloning is often seen as a violation of the sanctity of life and divine order. The belief that life begins at conception, and that human beings should not “play God,” underpins this objection. Cloning, in this view, is a dangerous overreach into realms best left untouched.

Islamic perspectives are varied, but many scholars argue that cloning interferes with natural procreation, which is considered a sacred bond between man and woman. However, therapeutic cloning that does not involve full human reproduction may be more permissible under certain interpretations, especially if it offers medical benefits.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, where reincarnation and karma are central concepts, the ethics of cloning can be more flexible. The cloned body may be seen as merely a vessel for a soul or consciousness that follows its own path, separate from the genetic material it inhabits. However, the instrumentalization of life for human desire is still viewed with caution.

Cultural values also shape the cloning debate. In individualistic societies, the right to choose one’s reproductive path may weigh more heavily. In collectivist cultures, the social implications—family honor, communal values, and intergenerational duties—may take precedence.

The Legal Landscape: A Global Patchwork

The legality of human cloning varies widely across the world, reflecting the diversity of ethical views. Most countries ban reproductive cloning outright, citing the ethical, social, and scientific concerns. However, therapeutic cloning exists in a gray zone, permitted in some nations under strict regulation and banned in others.

The United States, for example, does not have a comprehensive federal law banning cloning. Instead, the practice is restricted through a patchwork of state laws and limitations on federal funding. The United Kingdom allows therapeutic cloning under licenses granted by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) but forbids reproductive cloning. Countries like Germany, France, and Canada prohibit all forms of human cloning, while others remain silent or ambiguous.

This uneven regulatory environment raises the specter of “cloning tourism,” where individuals might travel to jurisdictions with looser laws to pursue cloning procedures. The absence of international consensus makes it difficult to monitor or control such activities, amplifying the need for a global ethical dialogue.

Slippery Slopes and Designer Babies

One of the most persistent concerns about human cloning is the slippery slope it presents. If cloning becomes accepted, what comes next? Would society begin to favor certain traits—intelligence, physical attractiveness, athletic prowess—and clone individuals who embody them? Would we edit embryos not just for health, but for enhancement?

This fear dovetails with the debate over gene editing technologies like CRISPR, which already allow scientists to modify the DNA of embryos. While the goal is often to eliminate genetic diseases, the line between therapy and enhancement is thin. Cloning could be the next step toward a world of designer babies, where parents—and perhaps even governments—choose the characteristics of future citizens.

Such a future raises chilling ethical questions. Who decides what traits are desirable? Would diversity be sacrificed for uniformity? Could cloning exacerbate existing inequalities, giving the wealthy access to biologically “better” offspring? And perhaps most troubling, would clones ever be used as means to an end—organ donors, military conscripts, or experimental subjects?

Human Rights and Personhood

The issue of rights is central to the cloning debate. If a human clone were born tomorrow, what rights would they have? Legally, they should be entitled to all protections afforded to any other person. But in practice, the societal treatment of clones could be discriminatory or exploitative.

Would they be viewed as full individuals, or as copies with a diminished status? The prospect of creating humans in a lab environment could foster a mindset in which clones are seen as products—owned, controlled, and perhaps even discarded if they fail to meet expectations.

This undermines the principle of human dignity enshrined in international human rights law. Every person, regardless of origin, has intrinsic worth and autonomy. Any approach to cloning must begin with this foundational ethical commitment: that a clone is a person, not a possession.

The Emotional Terrain: Parenting and Relationships

Human cloning does not only affect the clone. It reshapes the entire fabric of relationships—parenthood, kinship, and love. In traditional reproduction, children are a mix of both parents, a biological testament to their union. In cloning, this dynamic changes dramatically. The genetic contribution comes from a single individual, with no biological second parent.

How would this affect the parental bond? Would a clone be treated more like a child or a second self? Would they feel like an experiment, a project, or an object of obsession? The psychological terrain here is fraught and largely uncharted.

Some ethicists worry that cloning could fuel narcissistic impulses, with people creating replicas of themselves as a way to cheat mortality or express vanity. Others fear that cloned children might live under the shadow of their progenitor’s identity, pressured to fulfill a prewritten destiny rather than discovering their own.

Hope or Horror? The Future of Human Cloning

As biotechnology races forward, the ethical landscape becomes ever more complex. Scientists are edging closer to overcoming the technical challenges of human cloning. Stem cell research, synthetic biology, and artificial wombs all suggest a future where cloning could become feasible.

But should we embrace this future? Should we create human life in a lab, not to cure disease or save lives, but simply because we can?

Some argue that cloning may be justified if done with proper oversight, transparency, and respect for human dignity. Others believe the risks—psychological, societal, and existential—are too great. What is clear is that the debate cannot be left solely to scientists or politicians. It belongs to all of us.

As we stand on the brink of this profound frontier, we must ask ourselves: what kind of society do we want to be? One that honors the mystery of life, or one that seeks to master it? One that cherishes diversity and uniqueness, or one that dares to replicate it?

Conclusion: Ethics, Empathy, and the Essence of Humanity

The ethics of human cloning is not just a question of science, but a mirror held up to our deepest values. It challenges us to reconsider what it means to be human, to be free, to be loved. In the face of dazzling technological power, our moral compass becomes more vital than ever.

Medical science offers possibilities—but it is philosophy, ethics, and empathy that must guide their use. We must ensure that our pursuit of knowledge never eclipses our reverence for life. Whether or not human cloning ever becomes a reality, the debate it inspires will continue to shape our understanding of identity, autonomy, and the essence of humanity itself.