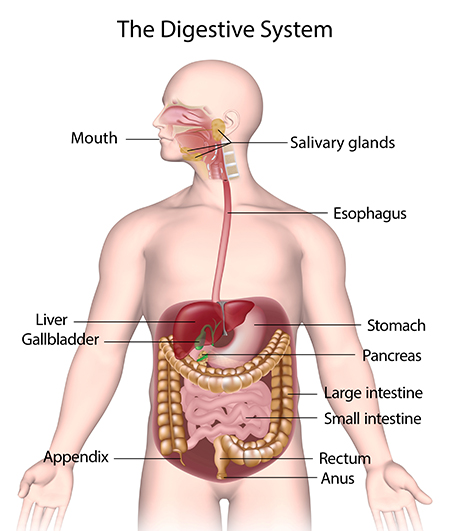

Every time you bite into a juicy apple, slurp a spoonful of hot soup, or nibble a piece of chocolate, you’re setting off one of the most complex, coordinated, and fascinating biological symphonies inside your body—the process of digestion. From that first satisfying crunch to the moment nutrients are absorbed deep within your cells, your digestive system is working around the clock, transforming food into life-sustaining energy, rebuilding materials, and essential molecules.

But what exactly happens between the first bite and the final… flush? How does your body take something as simple as a sandwich and turn it into the nutrients that power your heartbeat, your brain, your bones, and your breath?

Let’s journey through the entire digestive process—step by step, organ by organ—unraveling the mysteries and mechanics of the inner engine that keeps you alive. Prepare for a deep dive into enzymes, acids, muscular waves, bacterial allies, and the microscopic drama playing out inside your gut every day.

The Mouth: Where Digestion Begins

Digestion doesn’t begin in your stomach. It starts the moment you smell, see, or even think about food. That’s when your salivary glands kick into gear, producing a fluid that not only moistens your mouth but is rich with enzymes and electrolytes that kick off digestion.

As you chew, your teeth break food into smaller pieces—a mechanical process called mastication. But while your teeth are grinding, your saliva is hard at work chemically breaking down carbohydrates thanks to an enzyme called amylase. This is the beginning of chemical digestion.

Your tongue helps roll food into a small, swallowable lump called a bolus, and pushes it toward the back of your throat. That’s when you unconsciously initiate a process known as deglutition—the act of swallowing.

The Pharynx and Esophagus: Food on the Move

Once the bolus reaches the back of the mouth, it enters the pharynx, a shared space used for both breathing and swallowing. Here, a small flap of cartilage called the epiglottis closes off the windpipe to prevent choking, ensuring food travels down the esophagus instead of into your lungs.

The esophagus is a muscular tube about 25 centimeters (10 inches) long. It doesn’t rely on gravity to move food downward. Instead, it uses a rhythmic, wave-like motion known as peristalsis. Think of it as a smooth muscle massage pushing the food along, regardless of whether you’re standing up, lying down, or doing a headstand.

At the end of the esophagus is the lower esophageal sphincter, a circular muscle that acts as a gatekeeper, allowing food into the stomach while preventing stomach acid from flowing backward (a malfunction here leads to acid reflux or heartburn).

The Stomach: Mixing, Mashing, and Marinating

Once inside the stomach, your food encounters a harsh but carefully regulated environment. The stomach is both a storage tank and a digestion powerhouse. Its muscular walls churn and mix the food with gastric juices, creating a semi-liquid mixture known as chyme.

Gastric juices are a potent cocktail containing:

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl): This acid kills most bacteria and creates an extremely acidic environment (pH 1.5 to 3.5), which helps break down proteins and activates digestive enzymes.

- Pepsin: An enzyme that begins the digestion of proteins by breaking them into smaller peptides.

- Mucus: Protects the stomach lining from being digested by its own acid and enzymes.

The stomach can hold up to 1.5 liters of food and fluid at a time. Its muscular contractions knead and roll the chyme for hours. Contrary to popular belief, very little absorption happens here—except for a few substances like alcohol, aspirin, and water.

Once the food is adequately mixed and broken down, the pyloric sphincter at the base of the stomach opens, allowing chyme to enter the small intestine in small, controlled bursts.

The Small Intestine: The Absorption Powerhouse

The small intestine is a marvel of biological engineering. At around 6 meters (20 feet) long, it’s the longest part of the digestive system, and it’s where most digestion and nutrient absorption takes place.

It has three major parts:

Duodenum

This is the first 25-30 cm (10-12 inches) of the small intestine. It receives chyme from the stomach, but more importantly, it also receives secretions from two vital organs:

- The pancreas, which produces enzymes like trypsin (for proteins), lipase (for fats), and amylase (for carbs), as well as bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid.

- The liver, via the gallbladder, which supplies bile—a greenish fluid that emulsifies fats, breaking them into tiny droplets that enzymes can easily digest.

This part of the intestine is like a chemical processing plant, where the food is saturated with enzymes, neutralized, and emulsified for further digestion.

Jejunum

This midsection is where most nutrient absorption occurs. Its inner surface is covered in villi—tiny, finger-like projections that massively increase surface area. Each villus is lined with even smaller projections called microvilli, forming a “brush border” that maximizes contact with nutrients.

Through these structures, carbohydrates are absorbed as simple sugars (like glucose), proteins as amino acids, and fats as fatty acids and glycerol. These nutrients pass into the capillaries (blood vessels) or lacteals (lymphatic vessels) inside each villus.

Ileum

The final part of the small intestine continues absorbing nutrients, particularly vitamin B12 and bile salts. Anything not absorbed here will pass into the large intestine.

The entire journey through the small intestine takes several hours. Meanwhile, muscular contractions called segmentation mix and move the chyme along, ensuring maximum contact with the absorptive lining.

The Large Intestine: From Liquid to Solid

Whatever remains after the small intestine—mostly water, electrolytes, fiber, and dead cells—enters the large intestine, or colon, through a small valve known as the ileocecal sphincter.

The large intestine is about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long and includes several key segments:

- Cecum: The entry chamber, connected to the appendix—a small, tube-like organ once thought useless, now believed to support gut flora.

- Ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon: These sections absorb water and salts, turning the chyme from a liquid sludge into a more solid material: feces.

- Rectum and anus: The final stretch, where waste is stored and eventually expelled.

But digestion doesn’t end when the food stops being useful to us. Inside the colon, trillions of bacteria—collectively called the gut microbiota—feast on leftover fiber, producing gases like methane and carbon dioxide, as well as essential vitamins like vitamin K and biotin.

This microscopic ecosystem is vital for immune function, mood regulation, and overall health. In fact, your body contains more microbial cells than human cells—a reminder that you are, in part, a walking ecosystem.

Accessory Organs: Helpers Behind the Scenes

Though they don’t touch food directly, several organs play critical roles in digestion:

Liver

The liver is the largest internal organ and performs over 500 functions. In digestion, its main job is to produce bile, which helps emulsify fats. It also filters toxins from the blood and stores glycogen, a form of glucose.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile, releasing it into the duodenum when fatty food is detected.

Pancreas

The pancreas acts as both an endocrine and exocrine gland. It secretes insulin and glucagon (which regulate blood sugar) and also produces digestive enzymes that break down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates.

Nervous and Hormonal Control: The Brain-Gut Axis

Digestion isn’t just a series of chemical reactions; it’s also controlled by a complex network of nerves and hormones.

The enteric nervous system—sometimes called the “second brain”—controls the gut’s function independently of the brain, regulating muscle contractions, enzyme release, and blood flow.

At the same time, hormones like:

- Gastrin (stimulates acid production)

- Secretin (stimulates bicarbonate release)

- Cholecystokinin (CCK) (stimulates bile and enzyme release)

coordinate digestion, ensuring everything happens in the right place at the right time.

This system can even communicate with your brain through the vagus nerve, influencing mood, hunger, and satiety. This is why stress or emotion can affect digestion—because your gut and brain are in constant conversation.

What Can Go Wrong?

The digestive system is robust but not infallible. Several common (and some not-so-common) disorders can disrupt its harmony:

- Acid reflux (GERD): When stomach acid leaks into the esophagus.

- Peptic ulcers: Caused by bacteria (H. pylori) or NSAIDs.

- Celiac disease: An immune reaction to gluten damaging the small intestine lining.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A functional disorder with symptoms like cramping and bloating.

- Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: Inflammatory bowel diseases that can cause pain, bleeding, and malabsorption.

- Constipation or diarrhea: Often caused by diet, dehydration, or disrupted microbiota.

Modern medicine continues to explore how diet, lifestyle, and gut flora affect digestion—and overall health.

Digestion and Diet: Food as Medicine

The food you eat isn’t just fuel—it’s information. It tells your body how to function. A diet rich in:

- Fiber (fruits, vegetables, whole grains)

- Healthy fats (olive oil, nuts, avocados)

- Lean proteins

- Fermented foods (yogurt, kimchi, kefir)

promotes a healthy gut and efficient digestion. Meanwhile, excessive sugar, processed food, or alcohol can inflame and disrupt the digestive tract.

Hydration is critical too—water helps dissolve nutrients, move food, and prevent constipation.

Exercise, sleep, and stress management also play key roles. The digestive system thrives in balance, not just in chemistry but in lifestyle.

Conclusion: The Marvel Within

From the moment you eat to the moment you excrete, your digestive system works tirelessly, converting meals into molecules that build your body, fuel your brain, and support your life.

It’s a process shaped by evolution, guided by microscopic allies, and controlled by intricate signals. It’s an orchestra of muscles, glands, enzymes, and neurons, all playing in harmony to sustain you.

Understanding digestion isn’t just about biology—it’s about appreciating the inner world that powers your outer one. So next time you take a bite, remember: you’re not just eating. You’re starting a journey—a chemical adventure that links your food, your body, and your very survival.