In the tangled green forests of Vancouver Island, where the Pacific coast breathes in ocean fog and exhales spruce-scented air, lies a river whose cold waters cut through time. Along the Puntledge River, in a slice of Canada better known for salmon than sea monsters, paleontologists have finally solved a decades-old mystery—a mystery that began with a fossil and ended with a name: Traskasaura sandrae.

It has been more than three decades since the bones of a long-necked marine reptile were first spotted protruding from Late Cretaceous shale in British Columbia’s Haslam Formation. For years, those fossils were admired, even celebrated, yet remained scientifically nameless—an enigma swimming in the fog of deep time. Now, in a newly published study in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology, an international team of researchers has officially identified these remains as belonging to a previously unknown genus and species of elasmosaur, a type of plesiosaur, a group of marine reptiles that ruled the seas during the age of dinosaurs.

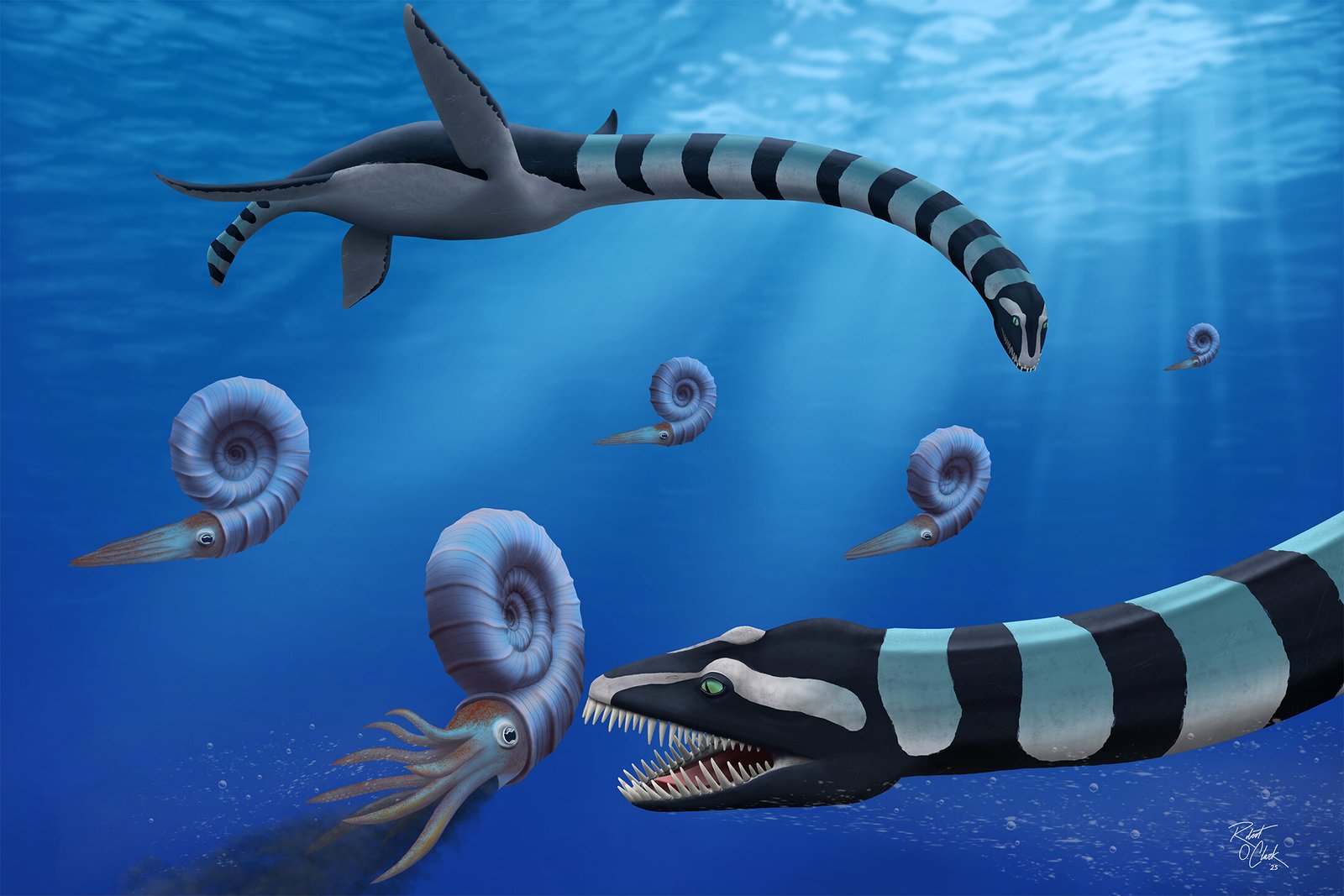

This new genus, Traskasaura sandrae, is more than just another elasmosaur. It is, in the words of lead author Professor F. Robin O’Keefe, “a very odd mix of primitive and derived traits,” a creature whose anatomy reveals not only its lineage, but its life: a predator built to dive, a hunter from above.

A New Kind of Sea Monster

At nearly 12 meters long with a neck that would put a giraffe to shame, Traskasaura sandrae was an apex predator of its Late Cretaceous marine ecosystem. But this wasn’t just another long-necked plesiosaur. This one had teeth—robust, sharp, and unusually heavy. They weren’t built for slicing fish or snagging soft-bodied prey. They were built for crushing.

The research team, which includes scientists from the United States, Canada, and Chile, argues that Traskasaura’s formidable dentition was likely adapted to crack open the armored shells of ammonites, a now-extinct group of marine mollusks that were abundant in the region 85 million years ago. Ammonites had spiral shells and tough exteriors, but to Traskasaura, they may have been the crunchy center of a Cretaceous seafood platter.

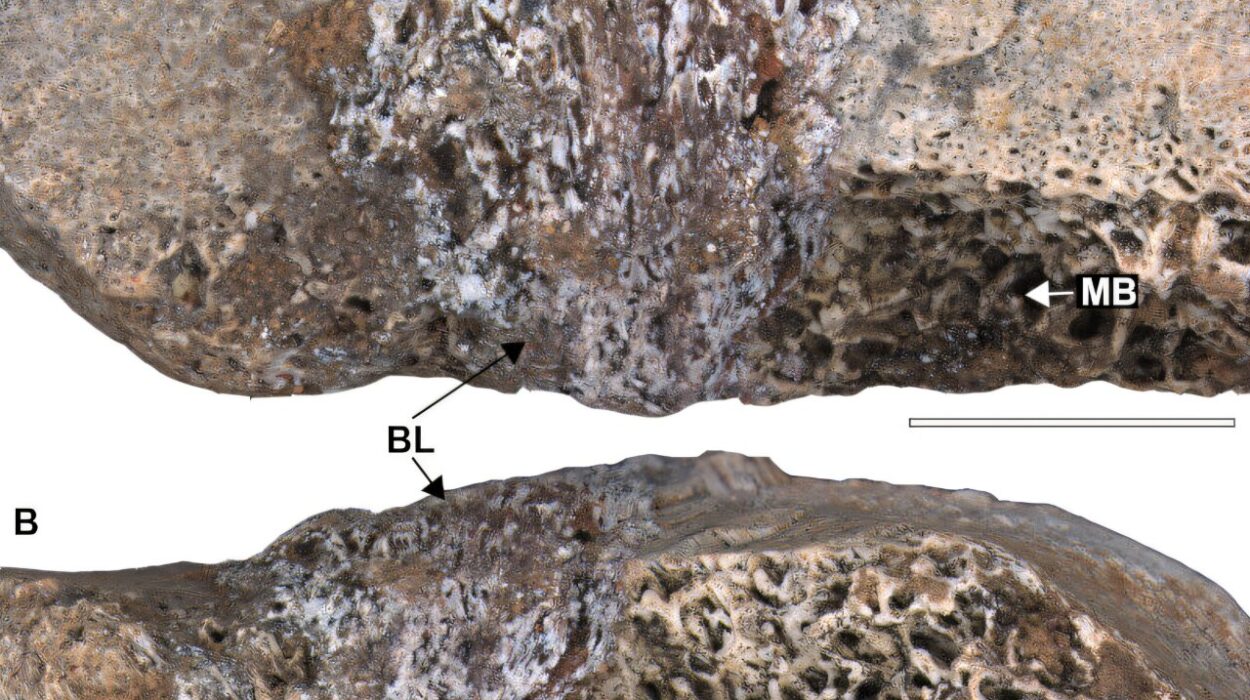

Yet it’s not just the teeth that make Traskasaura special. This elasmosaur possessed a suite of skeletal adaptations previously unseen in the group, including a shoulder girdle with highly unusual proportions and features that defy simple classification. It has elements common to both early and more evolutionarily advanced elasmosaurids. In other words, it was both ancient and new—a chimera of plesiosaur design.

The Fossil Puzzle Takes Shape

The story of Traskasaura begins in 1988, when amateur fossil hunters Michael and Heather Trask made a remarkable discovery along the Puntledge River. What they found was a partial skeleton embedded in marine sediments—ribs, vertebrae, and portions of the limbs of a long-dead reptile. Their find was brought to the attention of scientists, including the late Elizabeth Nicholls, a pioneering Canadian paleontologist who studied marine reptiles and helped document the find in a 2002 paper. Yet at the time, despite the fossil’s significance, there simply wasn’t enough diagnostic material to confidently name a new genus or species.

Over the years, more pieces emerged: an isolated humerus here, a well-preserved juvenile skeleton there. These fragments, gathered from various field expeditions and carefully curated at the Courtenay and District Museum and Paleontology Centre, slowly began to reveal a clearer picture. In the latest study, researchers examined three individuals—each different in age and preservation, but all displaying key anatomical features that matched up in telling ways. Together, they formed the composite identity of Traskasaura sandrae.

The genus name honors Michael and Heather Trask, whose discovery set the entire journey in motion, and combines their surname with sauros, the Greek word for “lizard.” The species name, sandrae, pays tribute to Sandra Lee O’Keefe (née Markey), a breast cancer warrior and cherished loved one of Professor O’Keefe. In this act of scientific naming, bones become biography, and paleontology becomes personal.

A Creature Built for Ambush

Plesiosaurs are famous for their swan-like necks, but Traskasaura takes it to another level. At least 36 preserved cervical vertebrae indicate a neck that may have contained over 50 bones in total. Long necks have puzzled scientists for decades—what evolutionary advantage could such an unwieldy feature provide? In Traskasaura’s case, the answer may lie in the fossil’s other surprising adaptations.

Based on its unusual shoulder structure and limb girdles, Traskasaura was likely an adept swimmer with powerful control over its vertical movements. These features suggest that it could dive sharply downwards—an uncommon mode of attack among known plesiosaurs. Rather than pursuing prey in open water, Traskasaura may have employed a stealthier strategy, hovering above ammonite-rich seafloors before plunging downward like a missile.

This behavioral hypothesis challenges long-standing assumptions about how elasmosaurs hunted. Most reconstructions depict them skimming through shallow waters or snatching fish in horizontal bursts. But Traskasaura might have turned the playbook upside down—literally. It wasn’t just fast or agile. It was tactical.

A Pacific Northwest Icon Millions of Years in the Making

Though it remained scientifically unnamed for years, Traskasaura never went unnoticed. In 2018, after a five-year campaign by paleontology enthusiasts and public supporters, the fossil was voted the Provincial Fossil of British Columbia, garnering nearly half the popular vote. In 2023, this designation became official, cementing the creature’s place in the cultural and natural heritage of the province.

It is rare for a scientific specimen to achieve civic status before it is properly named. But this speaks to the powerful connection people in British Columbia—and particularly in Courtenay—feel toward their prehistoric past. The Courtenay and District Museum has proudly displayed the fossil remains for years, offering visitors a glimpse into a time when giant reptiles prowled the seas that once covered the region.

With the official designation of Traskasaura sandrae, British Columbia now has a scientifically validated Mesozoic reptile to call its own. And unlike other famous North American elasmosaurs, such as Elasmosaurus platyurus or Thalassomedon haningtoni, this one hails from the Pacific, not the interior seaways of Kansas or South Dakota. It’s a sea monster rooted in coastal stone, in fog and forest, in tide and time.

A Beast Unlike Any Other

To paleontologists, the appeal of Traskasaura lies not only in its geographic novelty but in its biological oddness. It occupies a strange place in elasmosaur evolution, combining features of older, more basal forms with characteristics of more specialized, derived taxa. That’s not just an academic curiosity—it’s a window into how evolution can mix and match traits in unpredictable ways.

For example, while its vertebrae show elongation typical of long-necked elasmosaurs, its girdle morphology defies easy comparison. Even seasoned experts like O’Keefe admit to being baffled. “The shoulder, in particular, is unlike any other plesiosaur I have ever seen, and I have seen a few,” he remarks in the paper.

Initial thoughts speculated on a possible connection to Antarctic plesiosaurs, hinting at ancient migratory pathways or convergent evolutionary traits in cold-water marine ecosystems. But as analysis progressed, Chilean co-author Rodrigo Otero helped guide the team toward a different conclusion: this was something new, something local, and something that had evolved independently.

Traskasaura, then, is more than a new species—it is a statement about the unpredictable creativity of evolution, a reminder that even in a fossil record spanning hundreds of millions of years, new anatomical experiments continue to emerge from stone.

Legacy in Stone and Story

Fossils, at their core, are time travelers. They are messengers from epochs long vanished, fragments of flesh turned to stone that whisper of worlds we can barely imagine. In the case of Traskasaura sandrae, those whispers have finally been translated into a name, a description, and a story.

This isn’t just the tale of a new species. It’s the culmination of decades of effort—by fossil collectors who braved riverside cliffs, by curators who preserved fragile bones, and by scientists who puzzled over anomalous anatomy until something clicked. It is a story of community, of provincial pride, and of the relentless curiosity that fuels both amateurs and experts alike.

In honoring those who found the fossils, those who fought for them to be studied, and those who inspired the name, the discovery of Traskasaura stands as a triumph not only of science, but of human spirit.

And somewhere, beneath the moss and stone of Vancouver Island, perhaps more of these ancient sea dragons await. Waiting, like Traskasaura sandrae once did, for the patient eyes and steady hands that will bring their stories back to life.

Reference: A name for the Provincial Fossil of British Columbia: a strange new elasmosaur taxon from the Santonian of Vancouver Island, Journal of Systematic Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2025.2489938