From the sun-scorched surface of Mercury to the icy winds of Neptune, our solar system is a stage of planetary wonders. Each planet tells a story, shaped by billions of years of cosmic drama—collisions, volcanic rages, magnetic storms, and atmospheric alchemy. While we often learn the basics of the planets—names, positions, sizes—the deeper truths are stranger and more fascinating than fiction.

Let’s embark on a journey across the solar system, from the innermost planet to the distant blue ice giant, uncovering the secrets that make each world truly extraordinary.

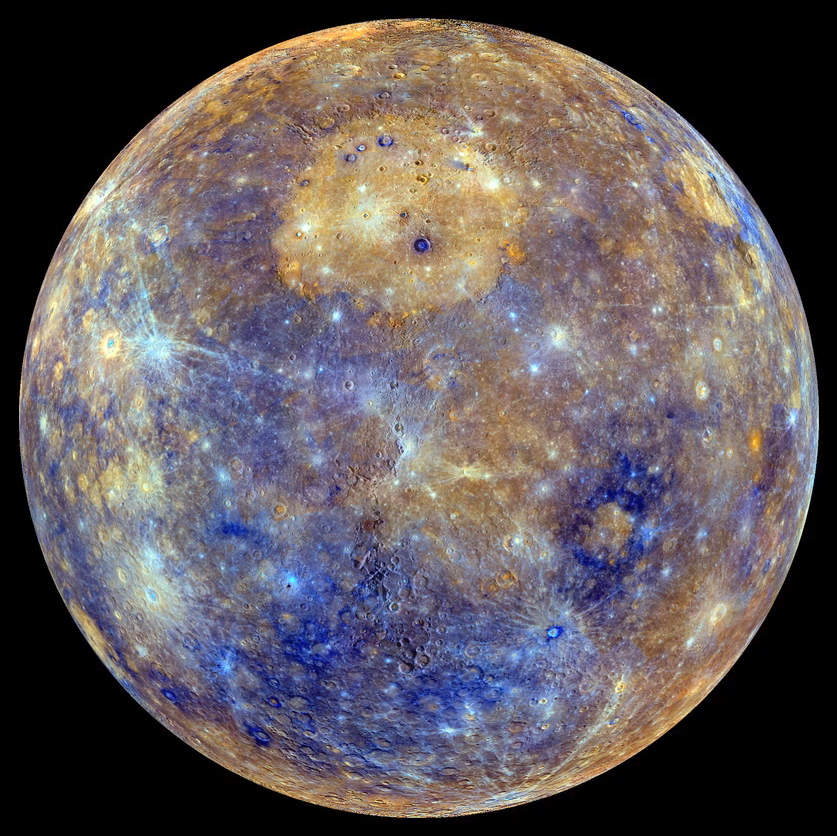

Mercury: The Mysterious Metal Ball

Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun, and that fact alone earns it a unique place in the solar family. But Mercury isn’t just a burnt rock; it’s a geological enigma and a gravitational outlier. Although it’s the smallest of the eight major planets, Mercury boasts a disproportionately large metallic core—over 80% of its radius. Scientists believe this core once made up a larger planet that lost much of its outer rock in a catastrophic collision, perhaps with a proto-planet in the early solar system.

Despite its proximity to the Sun, Mercury is not the hottest planet. Venus takes that title. However, Mercury holds the record for the planet with the greatest temperature extremes. During the day, surface temperatures soar above 800°F (430°C), while at night they plummet to -290°F (-180°C). With virtually no atmosphere to retain heat, Mercury lives in the extremes.

Another curiosity? Mercury has water ice. Deep inside shadowed craters near its poles—places that never see sunlight—scientists have found frozen water, likely delivered by ancient comets. So even this dry, airless world has the ingredients of one of life’s essentials.

And though it’s the fastest planet—completing a solar orbit in just 88 Earth days—it spins slowly. A single day on Mercury (sunrise to sunrise) takes 176 Earth days. You could stand on Mercury and watch the Sun rise, stop, reverse, and set again due to its odd rotational dynamics.

Venus: Earth’s Twisted Twin

If Mercury is a scorched wasteland, Venus is a hellish twin of Earth gone terribly wrong. Venus is almost the same size and composition as Earth, but that’s where the similarities end. Cloaked in thick clouds of sulfuric acid and an atmosphere composed of 96% carbon dioxide, Venus experiences a runaway greenhouse effect. Surface temperatures reach a crushing 900°F (475°C)—hot enough to melt lead.

Yet Venus’s surface is hidden beneath its cloud cover, and for centuries, scientists could only guess what lay beneath. It wasn’t until radar mapping by spacecraft like Magellan that Venus revealed its landscape: a world of vast volcanic plains, massive shield volcanoes, and strange, continent-sized plateaus.

Venus also spins backward—slowly. One day on Venus is longer than its year. It takes 243 Earth days to rotate once, but only 225 days to orbit the Sun. And if you stood on Venus, the Sun would rise in the west and set in the east.

Curiously, Venus may once have had oceans. Models suggest that it had enough water for shallow seas, but as the Sun grew hotter, the water evaporated, and the hydrogen escaped into space. Without oceans to absorb carbon dioxide, the atmosphere thickened, creating the inferno we see today.

Venus is also Earth’s closest planetary neighbor—not just in distance, but in orbital alignment. For much of Earth’s orbit, Venus is the closest planet to us, more often than Mars. Yet despite its closeness, Venus remains a mystery—a warning about the delicate balance of habitability.

Earth: The Oasis of Life

It’s easy to take Earth for granted, but it is nothing short of miraculous. It’s the only known planet with life, the only world with liquid water on its surface, and the only one with plate tectonics driving the cycling of carbon and nutrients across the globe.

What sets Earth apart is its balance. It’s not too close to the Sun like Venus, nor too far like Mars. Its atmosphere has just enough greenhouse gases to keep temperatures stable. Its magnetic field shields us from deadly solar radiation, and the Moon stabilizes our axial tilt, preventing chaotic swings in climate.

Earth’s biosphere isn’t just a passive passenger—it shapes the planet. Microbes helped create the oxygen-rich atmosphere we breathe. Trees and oceans regulate carbon levels. Life and geology are intertwined in a symbiotic dance.

And then there’s the Moon. Earth’s large natural satellite is unusual—far too big relative to the planet. The leading theory is that a Mars-sized body struck early Earth, ejecting debris that eventually formed the Moon. Without this event, Earth’s rotation and climate might have been wildly unstable.

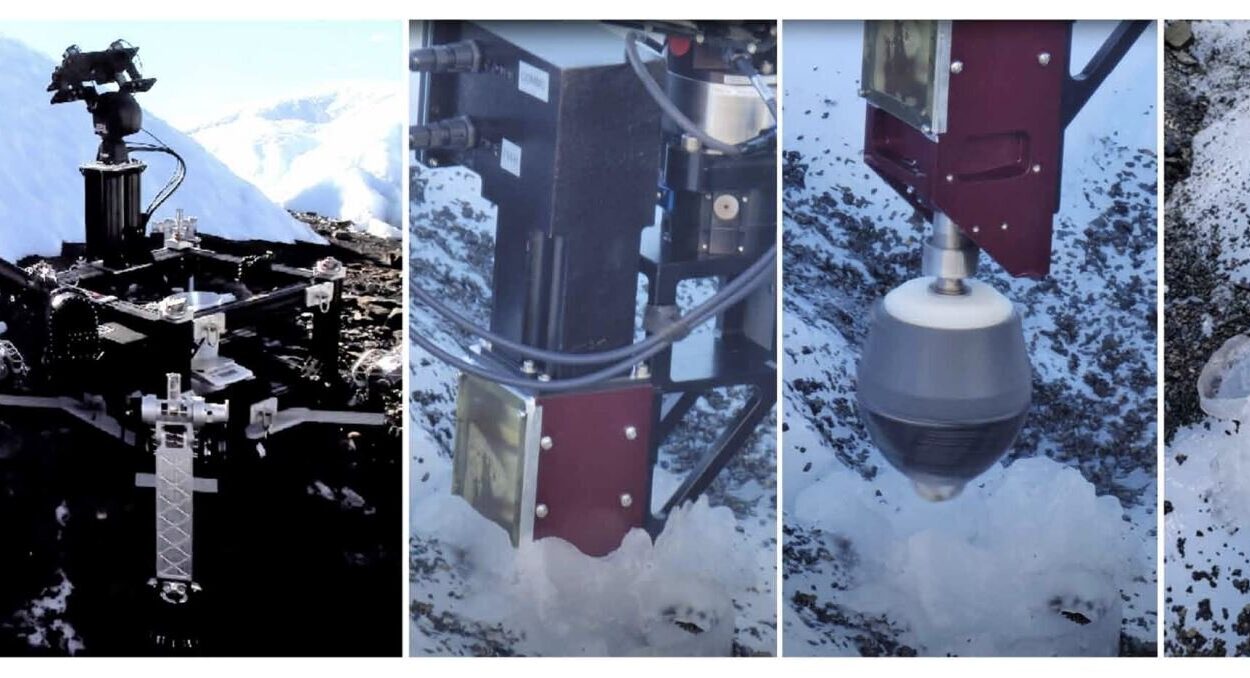

Though it’s our home, Earth is a world of ongoing discovery. From the deep ocean trenches to the microbial life hidden under Antarctic ice, Earth continues to surprise and remind us that the extraordinary doesn’t have to be extraterrestrial.

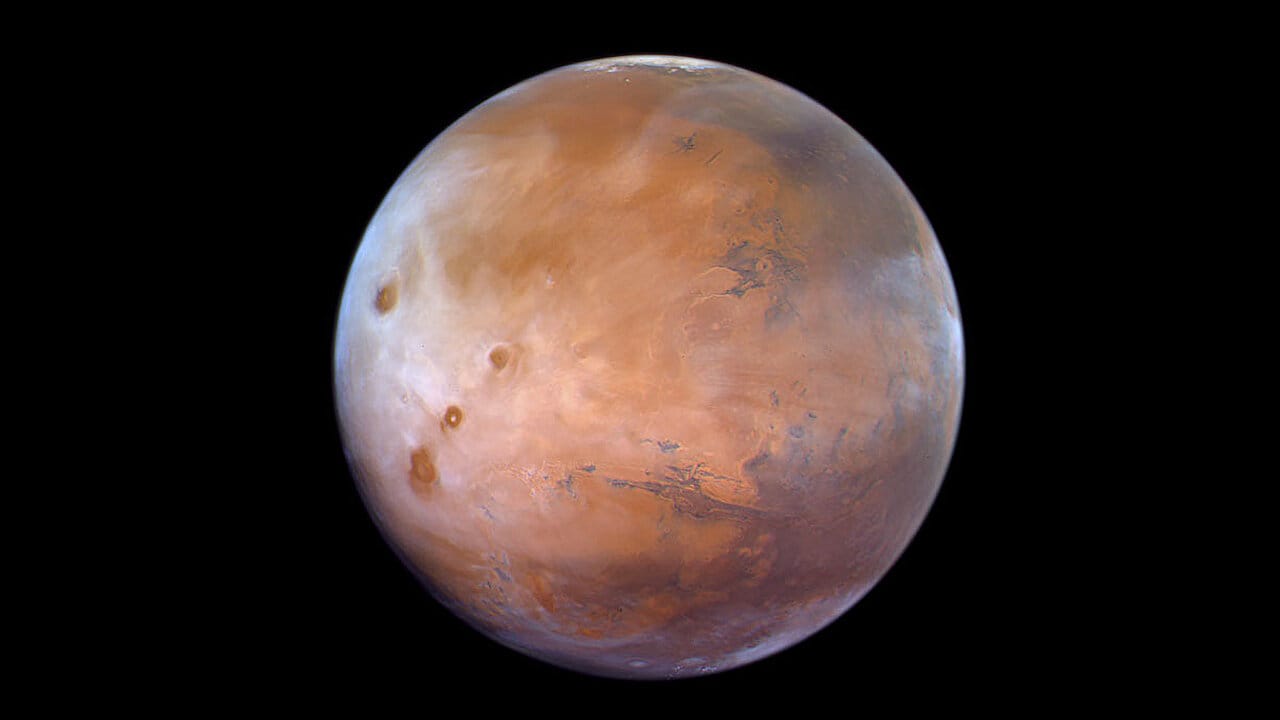

Mars: The Desert of Lost Waters

Mars is the dream of every planetary romantic—a world that may have once been like Earth, and perhaps could be again. Today it’s a cold desert, swept by dust storms and riddled with canyons, but its history tells of rivers, lakes, and even oceans.

The surface of Mars bears clear evidence of water erosion—dried riverbeds, deltas, and flood plains. Ancient lake beds have been mapped by orbiters, and rovers have found minerals that only form in water. While the atmosphere is now thin and frigid, it likely was thicker in the past, warmed by greenhouse gases and volcanic activity.

Mars is home to Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system, and Valles Marineris, a canyon system that would dwarf Earth’s Grand Canyon. These features speak of a geologically active past, though today Mars’s core is largely inactive.

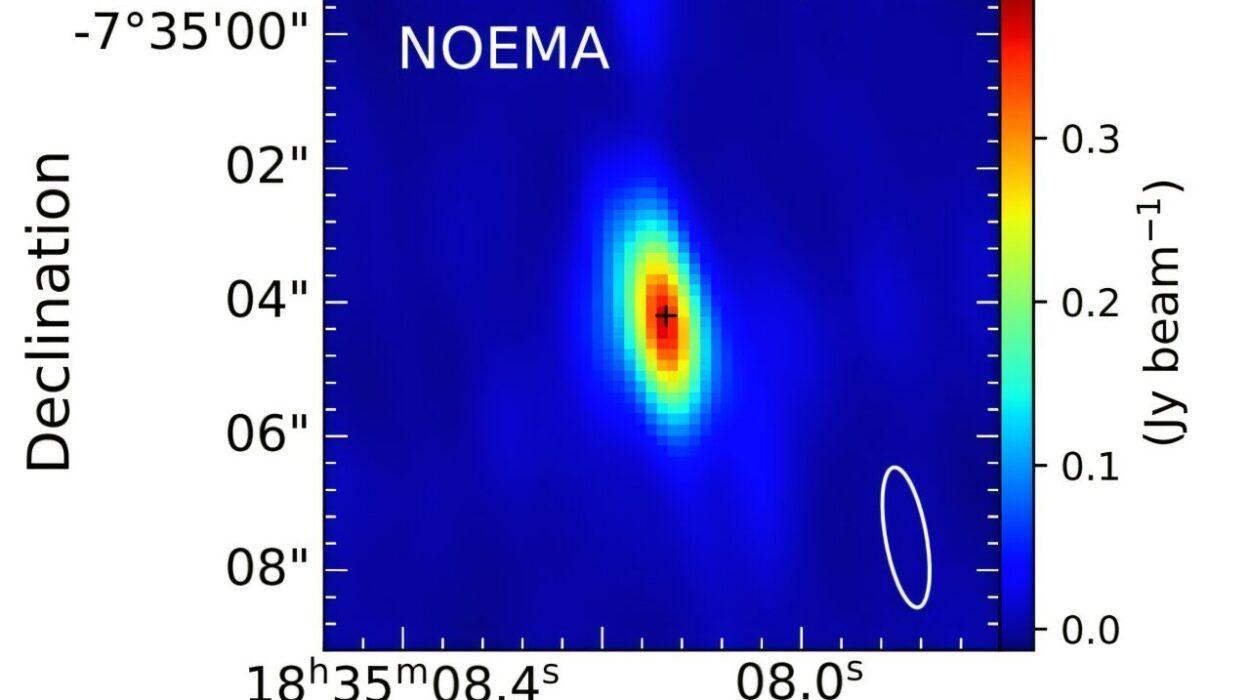

Beneath the surface, however, Mars still holds secrets. Subsurface radar has detected what may be briny lakes under its southern polar ice cap. If confirmed, they could be potential habitats for microbial life.

Mars’s reddish hue comes from iron oxide—rust—coating its surface. Its two moons, Phobos and Deimos, may be captured asteroids, and their irregular shapes and orbits add to Mars’s mystique.

Mars is the only other planet we’ve sent rovers to explore. The dream of colonizing Mars may be decades away, but each mission peels back another layer of this enigmatic world.

Jupiter: King of the Planets

Jupiter is the solar system’s heavyweight champion. With a mass more than twice that of all the other planets combined, Jupiter’s gravity has shaped the architecture of the solar system. It shepherds asteroids, protects the inner planets from comets, and may even have played a role in Earth’s habitability.

A gas giant, Jupiter has no solid surface. Its swirling atmosphere is dominated by hydrogen and helium, and its top layers are marked by storms larger than Earth. The most famous is the Great Red Spot, a colossal storm that’s raged for at least 350 years and possibly much longer. Winds inside the storm reach speeds of 400 mph, and it’s so big that three Earths could fit inside.

Beneath its clouds, pressure rises to extreme levels, and hydrogen is compressed into a strange, metallic form that may conduct electricity and generate Jupiter’s enormous magnetic field—14 times stronger than Earth’s.

Jupiter’s magnetosphere is the largest structure in the solar system, extending millions of kilometers into space. It traps radiation, creating a deadly environment for spacecraft.

Yet Jupiter isn’t alone. It has at least 95 moons, and several of them are worlds unto themselves. Europa, with its icy crust and subsurface ocean, may be one of the best candidates for life. Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system, larger than Mercury, and it even has its own magnetic field. Io, meanwhile, is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, with eruptions powered by Jupiter’s tidal forces.

Jupiter isn’t just a planet—it’s a miniature solar system in its own right.

Saturn: The Lord of the Rings

Saturn is perhaps the most visually stunning planet. Its majestic rings, first observed by Galileo in 1610, remain one of the most iconic sights in astronomy. Composed of ice particles ranging from microns to meters across, the rings are a delicate balance of gravity and motion, constantly shaped by Saturn’s moons.

But Saturn is more than just rings. Like Jupiter, it is a gas giant, mostly hydrogen and helium, with violent storms and rapid rotation. A day on Saturn lasts just 10.7 hours, and its equator bulges from the centrifugal force.

Saturn’s density is so low that it would float in water—if you could find a bathtub big enough. This low density hides a compact, metallic hydrogen core and a dynamic interior that may generate its own magnetic field.

Its moon Titan is a world of particular interest. Titan has a thick nitrogen-rich atmosphere, rivers and lakes—not of water, but of methane and ethane. It’s the only moon with a dense atmosphere and weather cycle, complete with rain and possibly cryovolcanoes. Beneath its surface may lie a salty, subsurface ocean.

Another moon, Enceladus, spews geysers of water vapor and ice from its south pole. These plumes contain organic molecules and hint at a subsurface ocean in contact with a rocky core—a tantalizing possibility for life.

Saturn’s rings may be young, only 100 million years old, and might vanish over time as material falls into the planet. In cosmic terms, Saturn’s beauty is ephemeral—a reminder of the solar system’s ever-changing nature.

Uranus: The Tilted Ice Giant

Uranus is a planet of oddities. Pale blue-green in color due to methane in its atmosphere, Uranus orbits the Sun on its side—its axis tilted by 98 degrees. This means that for decades at a time, one hemisphere faces the Sun while the other lies in darkness.

This extreme tilt is likely the result of a massive collision early in the planet’s history. The result is a planet with seasons more bizarre than any other. A single Uranian year lasts 84 Earth years, with each pole getting 42 years of continuous sunlight followed by 42 years of night.

Uranus is classified as an ice giant, distinct from gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn. Its atmosphere contains heavier elements such as water, ammonia, and methane ice. Its interior is cold and dim, emitting little heat—a mystery, since other giant planets radiate more energy than they receive.

Its magnetic field is equally strange—tilted at 59 degrees to its axis and offset from the planet’s center. This results in a lopsided, wobbling magnetosphere unlike any other in the solar system.

Uranus has 27 known moons, many named after characters from Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. Its ring system is faint but complex, with dark, narrow bands of dust and debris.

Rarely visited—only Voyager 2 has flown by—Uranus remains one of the least understood major planets. Future missions may uncover more about this cold, tilted mystery.

Neptune: The Windy World

Neptune, the eighth and farthest planet from the Sun, is a realm of deep blue mystery. Discovered in 1846 through mathematics rather than observation, Neptune was the first planet found by predicting its gravitational effects on Uranus. This marked a triumph of Newtonian physics and cemented the idea of an ordered cosmos.

Though similar in size and composition to Uranus, Neptune is more active and more mysterious. Its atmosphere, rich in methane, creates its deep azure color. But what lies beneath the clouds is still poorly understood.

Despite its distance from the Sun, Neptune has the fastest winds in the solar system—up to 1,200 mph. These supersonic winds whip through the atmosphere, creating massive storm systems like the Great Dark Spot, once seen by Voyager 2.

Neptune radiates more heat than it receives, and no one knows exactly why. Some believe its core is hotter or that internal friction produces extra energy.

Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, is a captured object—likely a Kuiper Belt object ensnared by Neptune’s gravity. It orbits in the opposite direction of Neptune’s rotation, a sign of its alien origin. Triton has geysers, a thin atmosphere, and a frozen surface that hints at subsurface activity.

Neptune marks the edge of the classical solar system, but beyond it lie thousands of icy worlds—Pluto, Eris, and others—that make up the Kuiper Belt.

Neptune is both an end and a beginning: the last major planet and the gateway to the solar system’s frozen frontier.