What if everything we see, feel, and know about the world around us is not truly real? The question of whether reality is an illusion has fascinated philosophers, scientists, mystics, and artists for centuries. In contemporary times, advances in physics have propelled this ancient question into a modern scientific arena, where empirical inquiry and theory meet the age-old mysteries of human perception.

When we look around, we trust our senses to convey an accurate picture of reality. The blue sky, the solidity of the chair beneath us, the warmth of sunlight—these experiences feel unquestionably real. Yet, beneath this intuitive certainty lies a paradox: what we perceive is mediated by the brain, filtered through sensory organs, and interpreted by neural networks. Could this intricate biological process be creating a carefully constructed illusion?

Modern physics further complicates this picture. At the smallest scales, the universe behaves in ways that defy classical intuition. Quantum mechanics reveals a world where particles exist in probabilistic states until observed, and the act of measurement itself changes what is measured. General relativity tells us that spacetime bends and warps, and even time itself is relative. Some theoretical physicists even propose that the universe might be a kind of hologram, where three-dimensional reality emerges from information encoded on a distant surface.

This article embarks on a journey through physics, neuroscience, and philosophy to explore whether reality is truly as solid as it seems or if it is, in essence, an illusion—an exquisitely sophisticated construct of perception and information.

The Foundations of Reality: What Do We Mean by “Real”?

Before delving into physics or perception, it’s crucial to clarify what “reality” means. Reality, in a common sense, is the state of things as they actually exist, independent of observation or belief. It’s the sum of all that is—matter, energy, space, time, and the laws governing them.

However, this notion becomes murky when we recognize that every experience of reality is mediated by a conscious observer. Philosophers have long debated whether reality exists independently of perception or if it is intrinsically linked to the observer’s mind.

René Descartes, the father of modern philosophy, famously concluded, “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”), emphasizing the undeniable certainty of one’s own consciousness as the foundation of existence. Yet, this does not guarantee the existence of the external world. The idea that the external world might be an illusion or a dream has been explored by Eastern philosophies like Buddhism and Hinduism and Western thinkers alike.

In contemporary philosophy, “realism” posits that there is a world that exists independently of our perceptions, whereas “idealism” argues that reality is fundamentally mental or immaterial. Between these extremes, various schools like phenomenology examine how experience shapes our understanding of reality without dismissing the external world’s existence.

This philosophical tension sets the stage for scientific inquiry. What does physics say about the nature of reality, and how does our brain’s perception fit into the picture?

The Brain: Architect of Perception

To understand whether reality is an illusion, we must first understand how perception works. Human experience is not a direct window to the external world. Rather, it is a simulation created by the brain.

Our sensory organs—eyes, ears, skin, nose, and tongue—detect physical stimuli: light waves, sound waves, pressure, chemical molecules. These signals are transformed into electrical impulses and transmitted to the brain. Here, billions of neurons process and interpret the data, constructing a coherent experience that we call reality.

Yet, the brain is far from a passive recipient. It actively fills in gaps, filters noise, and even generates experiences without external input. Optical illusions reveal how easily perception can be fooled. The famous “Rubin’s Vase” can be seen as either a vase or two faces depending on the viewer’s focus. The brain’s tendency to seek patterns and meaning sometimes creates perceptions that have no external counterpart.

Moreover, conditions such as phantom limb syndrome, where amputees feel sensations in a missing limb, demonstrate how perception can diverge from physical reality. Dreams and hallucinations are vivid examples of internally generated realities.

The philosopher Donald Hoffman argues that evolution has shaped perception not to show us reality as it is, but to give us a user-friendly interface that promotes survival and reproduction. According to this “interface theory of perception,” what we see is like a computer desktop—icons representing deeper, complex processes we don’t perceive directly.

Thus, while we trust our senses, they deliver a constructed version of the world, optimized for function rather than truth. Does this mean that objective reality is beyond our grasp, or does physics offer ways to probe deeper?

Classical Physics and the Illusion of Determinism

The classical physics of Newton, developed in the 17th century, described a universe that was deterministic, predictable, and absolute. Objects had definite positions, velocities, and properties, and time flowed uniformly everywhere. This worldview matched everyday experience and seemed to confirm a stable, external reality.

Under Newtonian physics, the universe resembled a giant clockwork mechanism, governed by fixed laws. The sense of reality was concrete, continuous, and reliable. This deterministic vision fostered the belief that the world was fully knowable if one had sufficient data.

However, classical physics did not answer all questions. By the late 19th century, phenomena like blackbody radiation, the photoelectric effect, and atomic spectra revealed cracks in the classical framework. The behavior of light and matter at microscopic scales resisted explanation, paving the way for a revolution in physics.

Quantum Mechanics: Reality as Probability and Observation

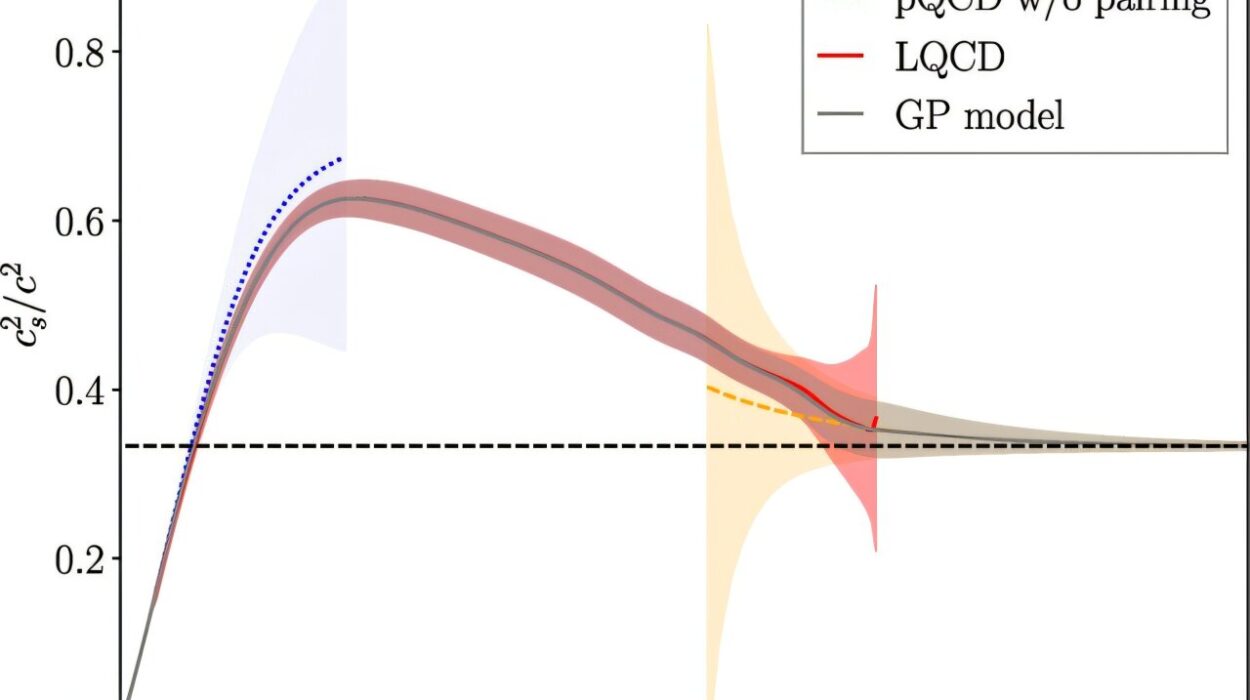

The advent of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century shattered the classical worldview. In the quantum realm, particles behave both as waves and particles, existing in superpositions of states until measured. This probabilistic nature of reality challenged the notion of definite, objective properties independent of observation.

One of the most famous thought experiments illustrating this is Schrödinger’s Cat. A cat in a sealed box is simultaneously alive and dead until someone opens the box and observes it, collapsing the quantum superposition into one definite outcome. This paradox highlights the role of observation in defining reality itself.

The Copenhagen interpretation, primarily developed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, holds that quantum systems do not have definite properties until measured. Reality, at its core, is indeterminate and shaped by the act of observation.

This interpretation raises profound questions: Is consciousness necessary to collapse the wavefunction? Does the observer create reality? Alternative interpretations such as the many-worlds theory suggest that all possible outcomes occur in branching universes, preserving determinism but multiplying realities.

Quantum entanglement further complicates the picture, where particles separated by vast distances instantly influence each other’s states. This phenomenon, which Einstein famously called “spooky action at a distance,” challenges classical notions of locality and causality.

In this quantum landscape, reality becomes a dynamic interplay between probabilities, information, and measurement—a far cry from the solid world of everyday experience.

The Role of Information and the Holographic Principle

Recent developments in theoretical physics propose that information might be more fundamental than matter or energy. The “it from bit” idea, popularized by physicist John Archibald Wheeler, suggests that everything physical is ultimately information at its core.

One of the most intriguing hypotheses connected to this idea is the holographic principle. Proposed through studies of black hole thermodynamics and string theory, it posits that all the information contained within a volume of space can be described by data encoded on its boundary—a lower-dimensional surface.

In this view, our three-dimensional reality may be a holographic projection of information on a two-dimensional surface, analogous to how a flat hologram can encode a three-dimensional image. If true, this would mean that the “solid” world we inhabit emerges from underlying informational patterns, blurring the line between reality and illusion.

While still speculative, the holographic principle unites gravity, quantum mechanics, and information theory in novel ways. Experiments and mathematical models continue to explore its implications, which could redefine our understanding of space, time, and existence itself.

Time, Space, and Relativity: Reality is Relative

Albert Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity further transformed our conception of reality. He showed that space and time are not absolute but interwoven into a four-dimensional fabric called spacetime. Time flows at different rates depending on the observer’s velocity and gravitational field, shattering the Newtonian idea of universal, uniform time.

This relativity means that events can appear different depending on one’s frame of reference. Two observers moving at different speeds may disagree on the order of events or the duration between them. Even the geometry of space bends near massive objects.

Relativity teaches us that reality is not a fixed stage but a flexible, dynamic entity shaped by matter and energy. This flexibility has been confirmed by countless experiments and lies at the heart of modern cosmology.

The strange behavior of time, combined with quantum uncertainty, suggests that our intuitive experience of a stable, objective reality is just one perspective among many possibilities.

Consciousness and Reality: The Observer Effect

If physics reveals that observation influences reality, what role does consciousness play? The “observer effect” in quantum mechanics points to a deep connection between mind and matter. Yet, the nature of consciousness remains elusive.

Some interpretations posit that conscious observation collapses the wavefunction, giving reality its definitive form. Others argue that the observer need not be conscious; any interaction that extracts information suffices.

Philosophers and neuroscientists grapple with the “hard problem” of consciousness—how subjective experience arises from physical processes. If perception is the gateway to reality, understanding consciousness becomes crucial to understanding reality itself.

The notion that reality depends on observation resonates with ancient spiritual ideas, where mind and matter are intertwined. Modern theories like integrated information theory (IIT) and quantum consciousness explore these frontiers, though no consensus exists.

Virtual Reality and Simulation Hypotheses

The rise of digital technology and virtual reality (VR) has reignited the question of whether our universe could be a simulation. The simulation hypothesis, advocated by thinkers like Nick Bostrom, suggests that an advanced civilization might run simulations so detailed that conscious beings within them perceive a fully “real” world.

This idea draws on the analogy that if technology continues to progress, simulations indistinguishable from reality could exist. We might ourselves be inhabitants of such a simulated reality.

Although speculative, this hypothesis pushes us to reconsider the meaning of reality and challenges the assumption that our universe is fundamentally “natural.”

Whether or not the simulation hypothesis is true, the experience of VR reminds us that perception can be manipulated and altered, blurring the line between illusion and reality.

Mystical and Philosophical Perspectives on Illusion

Beyond physics, many spiritual traditions have long asserted that the world we perceive is maya—illusion or appearance. Hinduism and Buddhism teach that the sensory world is transient and deceptive, masking the ultimate reality of consciousness or the absolute.

Mystics describe transcending ordinary perception to experience a unity beyond distinctions of self and other, subject and object. Such experiences challenge the assumption that our daily reality is the only or ultimate truth.

These perspectives offer a complementary viewpoint: that what science uncovers about the fundamental strangeness of the universe resonates with the ancient wisdom about the illusory nature of phenomena.

Bridging Science and Perception: Toward a New Understanding

The modern quest to understand reality demands integrating insights from physics, neuroscience, and philosophy. Reality, it seems, is not simply “out there” waiting to be observed, nor is it purely subjective. Instead, it arises from a complex interplay of objective laws, information, perception, and consciousness.

Scientific experiments continue to probe deeper into the quantum realm, revealing phenomena that strain classical understanding. Neuroscience uncovers how the brain constructs experience, sometimes diverging sharply from external stimuli. Philosophy challenges us to refine our concepts of existence and knowledge.

The boundaries between reality and illusion blur, encouraging humility and wonder. We may never fully grasp the “true” nature of reality, but the journey itself enriches our appreciation for the mystery and beauty of existence.

Conclusion: Reality as a Dynamic, Participatory Experience

Is reality an illusion? The answer is both yes and no. What we experience as reality is a constructed, filtered, and interpreted phenomenon—a participatory event involving the universe and the observer. It is neither a fixed, objective monolith nor a mere hallucination but a dynamic dance of information, observation, and consciousness.

Physics shows that reality at the fundamental level defies classical intuition, embracing probability, relativity, and informational depth. Our senses and brains craft a narrative that enables survival and meaning, shaping what we call real.

Philosophy and spirituality remind us that reality might transcend ordinary perception, inviting us to explore deeper layers of existence.

Ultimately, reality is not a static thing but a living process, a mystery to be engaged with rather than solved. By embracing this complexity, we open ourselves to a richer, more profound experience of the world—and our place within it.