A groundbreaking study from the University of Sydney has revealed that the consequences of an unhealthy diet extend far beyond the waistline. Published in the International Journal of Obesity, the research provides compelling new evidence that fatty and sugary diets don’t just damage physical health—they also dull the brain’s ability to find its way around. Specifically, it shows how regular consumption of junk food may impair the hippocampus, a brain region vital for spatial memory and navigation.

The Brain on Junk Food: What’s at Stake?

For years, scientists have warned that diets high in saturated fats and refined sugars can be detrimental to cognitive health. But while previous human studies have linked such eating patterns to cognitive decline, few have zeroed in on how exactly they impair brain function—especially when it comes to spatial navigation, a skill that is deeply rooted in the hippocampus. That’s precisely what this new research aimed to address.

Lead author Dr. Dominic Tran, an Australian Research Council DECRA Research Fellow, designed the study to bring a novel approach to the table. “One thing the hippocampus is important for is spatial navigation—the ability to remember places and how to get there,” Tran explained. “I wanted a way to test spatial navigation that was as close to real life as possible.”

A Maze Made of Calories and Neurons

Rather than using standard memory tests, Tran’s team crafted an immersive virtual reality (VR) maze to simulate a real-world navigation challenge. Participants, donning VR headsets, were asked to explore a 3D maze, relying on visual landmarks to locate a hidden treasure chest—an experimental stand-in for everyday memory tasks like remembering where you parked your car at the mall.

During the training phase, participants navigated the maze from a consistent starting point, locating the chest six times using the same visual cues. Over time, most participants became quicker at finding the chest, indicating spatial learning. But a key variable soon began to separate the sharp navigators from the sluggish ones: diet.

Fat, Sugar, and Fading Direction

Each participant completed a dietary questionnaire measuring how frequently they consumed high-fat, high-sugar foods—think fast food, desserts, sugary drinks. Researchers also assessed their body mass index (BMI) and working memory to control for general cognitive ability and health. Of the initial 120 university student participants, only 55 completed the full experiment due to technical issues or motion sickness from the VR.

Analysis revealed a stark difference: those who consumed more fatty and sugary foods exhibited a flatter learning curve—they improved less over repeated attempts. Worse yet, in the final test where the maze walls were removed and only external landmarks remained, participants with poor diets performed significantly worse. They finished further from the correct location, indicating weaker spatial memory. Notably, these results remained even after accounting for BMI and working memory.

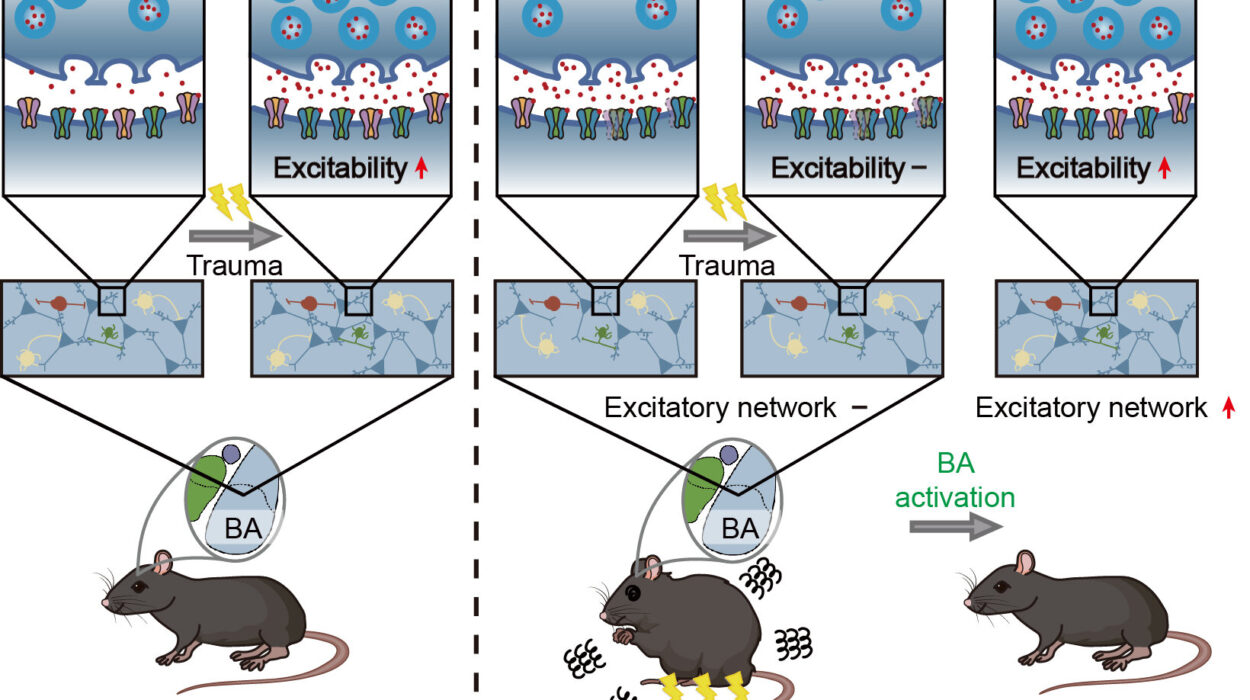

Hippocampus Under Fire: Echoes from Animal Research

The results eerily mirror findings from decades of animal research. In rodent studies, diets high in saturated fat and sugar impair hippocampal function, often before the animals even gain weight. Rats fed junk food struggle with spatial memory tasks—yet show no such deficits in other types of memory that depend on different brain regions. This suggests that the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to dietary assault.

In humans, Tran’s findings appear to reinforce that pattern. Participants’ working memory—a broader cognitive skill—was unaffected by diet. But their hippocampus-dependent navigation took a hit, aligning closely with what’s been seen in animal studies.

Virtual Reality as a Window into the Brain

One of the most innovative aspects of the study was its use of virtual reality to simulate natural navigation. “It’s a really sensitive tool that tells us about how the hippocampus is functioning,” Tran noted. “I think one of the biggest strengths of the study is in using virtual reality to truly assess people’s spatial navigation ability.”

By simulating a three-dimensional, first-person environment, VR provided a richer and more realistic test of memory than traditional screen-based tasks. Participants navigated from an eye-level perspective, just as they would in the real world. This allowed researchers to observe subtle differences in learning and recall that might otherwise go undetected.

However, there was a downside: nearly 40% of participants dropped out due to cybersickness—nausea and discomfort caused by VR immersion. It’s a tradeoff between ecological validity and participant comfort, but as VR tech continues to improve, this limitation may fade.

Correlation or Causation? The Scientific Caution

While the findings are compelling, they come with the classic scientific caveat: correlation doesn’t prove causation. It’s possible, albeit unlikely, that individuals with poorer spatial skills are more inclined to consume junk food. But a more plausible explanation, supported by decades of rodent studies, is that unhealthy diets cause hippocampal dysfunction.

Experimental animal studies have shown that high-fat, high-sugar diets can damage the hippocampus, and that these effects are reversible with dietary changes. Translating this into human models is the next challenge.

“I am really interested in testing if the memory impairments recover and uncovering the conditions around this recovery,” said Tran. “For example, how long does it take to recover and can we speed up recovery?”

The Limits of Self-Reporting and the Need for Broader Samples

As with many psychological studies, this research relied on self-reported dietary data—raising the risk of inaccuracies due to memory lapses or social desirability bias. Participants might underreport unhealthy food consumption or overestimate healthy habits.

Additionally, the sample was small and homogenous—mainly young, healthy university students in Sydney. This raises questions about generalizability. Would similar results hold true in older adults? In people from different cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds? Or in individuals already at high risk for cognitive decline?

These are open questions, but the study lays a strong foundation for future research. Larger, longitudinal studies with diverse populations and controlled dietary interventions could help confirm the link between diet and brain health more definitively.

Why This Matters: The Brain-Body Connection

At a time when rates of obesity and diet-related illness continue to climb globally, this research adds an urgent neurological dimension to the conversation. It’s not just about cholesterol, blood sugar, or waistlines—it’s about memory, navigation, and perhaps even dementia risk.

The hippocampus is among the first brain regions affected in Alzheimer’s disease. If unhealthy diets erode its function over time, they may not only impair everyday memory but potentially increase long-term vulnerability to neurodegenerative conditions.

The Road Ahead: Rethinking Brain Health Through Diet

This study joins a growing chorus of research suggesting that what we eat affects how we think, remember, and find our way in the world. The implications are profound: dietary choices could shape not only physical health but also cognitive ability and brain resilience.

As Tran emphasizes, future research should focus not only on understanding these effects but also on identifying recovery mechanisms. Could switching to a Mediterranean or whole-foods diet restore hippocampal function? Can exercise or cognitive training buffer against dietary harm?

The answers to these questions could revolutionize both nutritional science and cognitive health.

Final Thoughts: Beyond the Plate

In an era of fast food and convenience culture, the study serves as a sobering reminder: our brains may be paying the price for our dietary indulgences. The hippocampus, though tucked deep within the brain, is on the front lines of this invisible battle—navigating not just mazes, but the complexities of memory, learning, and daily life.

For now, the takeaway is simple but powerful: what you feed your body feeds your brain. The path to better memory and sharper cognition might just start with what’s on your plate.