In the quiet chambers of the eye, a startling story is unfolding—one that may help explain why some people emerge from COVID-19 with their minds shrouded in fog, and why others may unknowingly be edging closer to Alzheimer’s disease.

A new study led by researchers at Yale University has uncovered evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, can trigger changes in the brain that resemble those seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Even more remarkably, the scientists have identified a specific molecular pathway—neuropilin-1, or NRP1—that may be responsible, offering a potential target for treating brain fog and other neurological effects long after the infection has cleared.

The findings, published in Science Advances, shed light on how a virus that begins in the lungs can infiltrate the brain and disrupt cognitive function. And they suggest that the lingering “brain fog” many COVID-19 survivors experience may not be a temporary inconvenience—but the sign of deeper, potentially long-term neurological damage.

A Familiar Villain: Amyloid Beta

Alzheimer’s disease has long been marked by the ghostly buildup of amyloid beta plaques—clumps of proteins that form in and around brain cells, clogging communication and killing neurons. But a lesser-known theory, known as the antimicrobial hypothesis, suggests that amyloid beta isn’t just a toxic byproduct of disease. It may actually be part of the brain’s ancient defense system—a way of trapping invading microbes that breach the brain’s protective shield.

The hypothesis has been controversial for years. But now, COVID-19 may be offering unexpected support for it.

“There is growing evidence linking COVID-19 and brain fog,” says senior author Dr. Brian Hafler, MD, Ph.D., associate professor of ophthalmology and visual science at Yale School of Medicine. “While the mechanisms are not fully understood, scientists have found that SARS-CoV-2 can induce amyloid beta accumulation in the central nervous system.”

The Eye as a Mirror of the Brain

Because directly studying the human brain is incredibly invasive, Dr. Hafler and his team turned to a surprising stand-in: the retina. The retina, an extension of the central nervous system, is a thin layer of neural tissue at the back of the eye. Not only is it more accessible, but it also mirrors many of the brain’s biological processes.

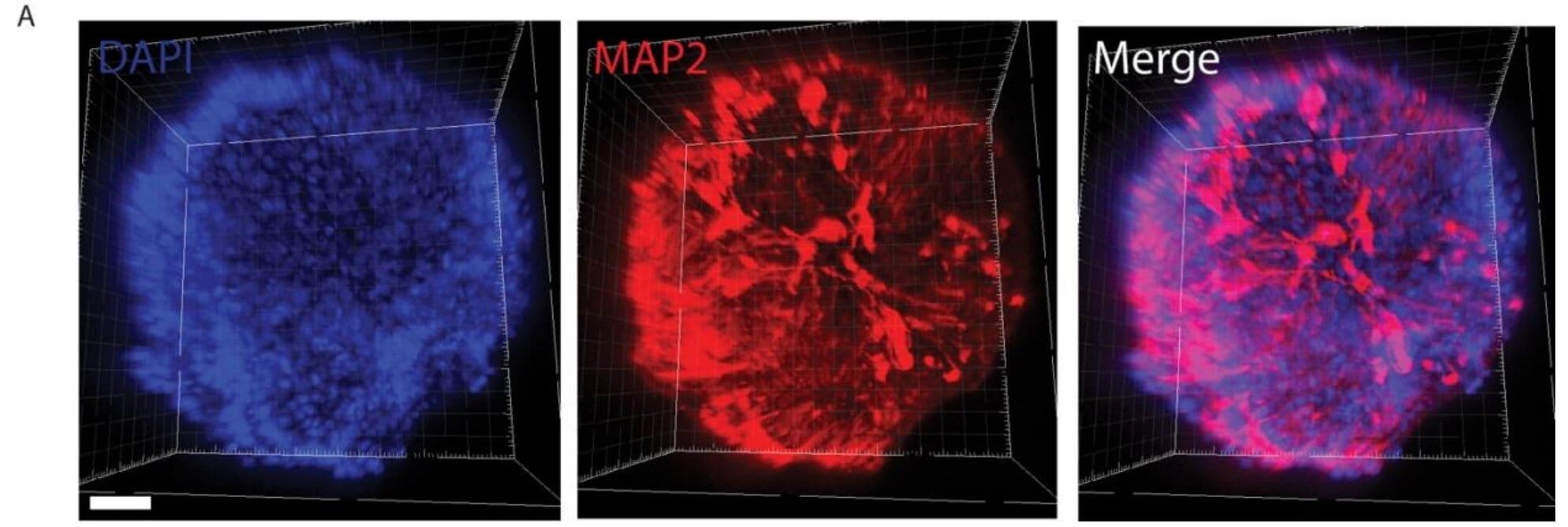

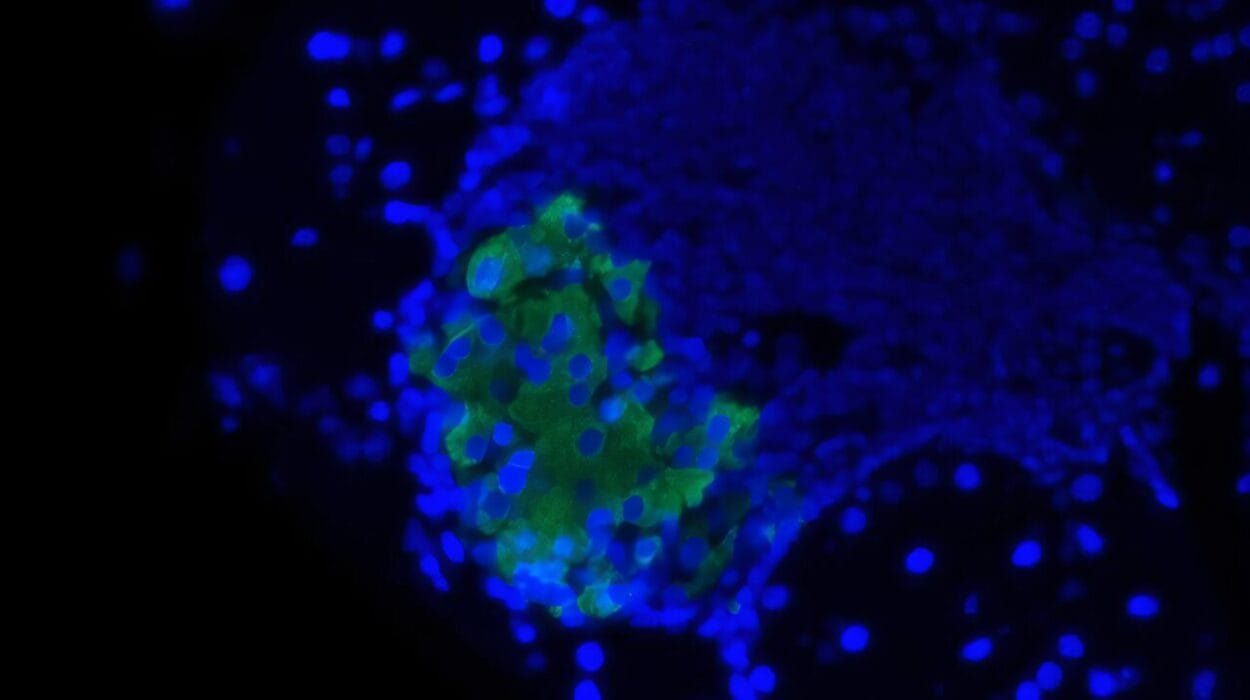

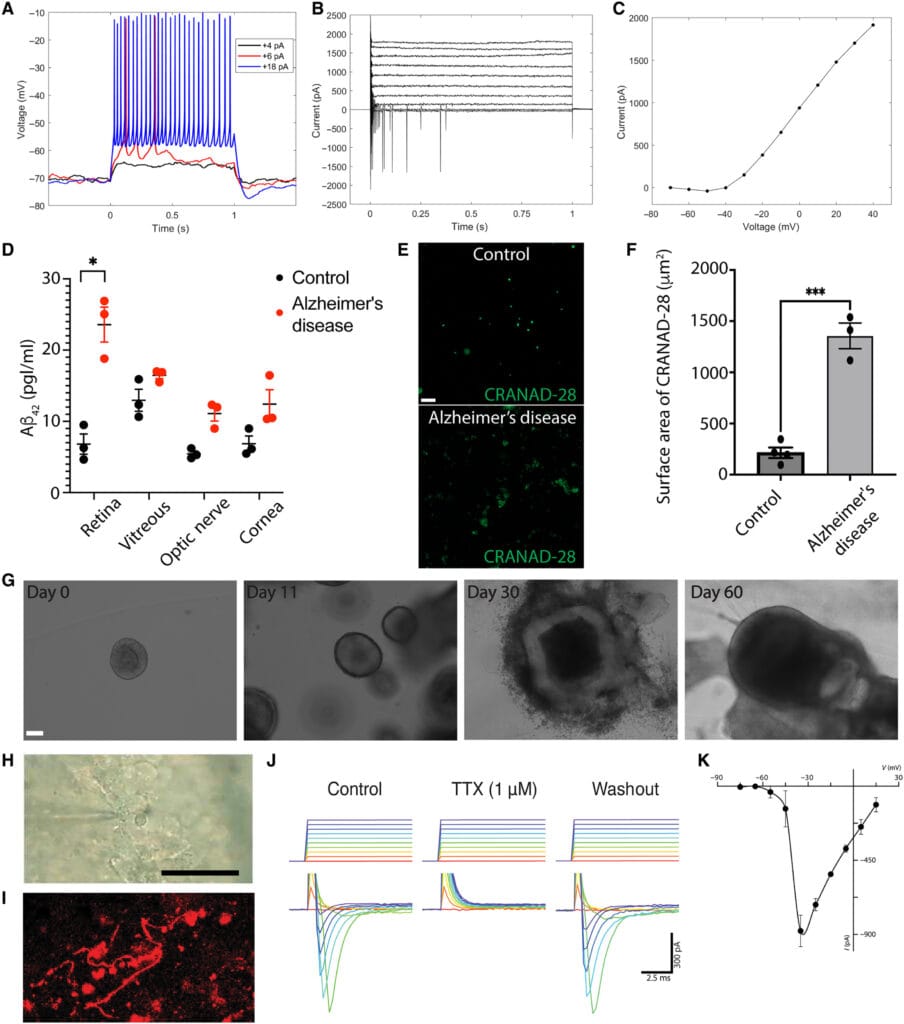

To study how SARS-CoV-2 might affect the brain, researchers used retinal organoids—miniature human retinas grown from stem cells in the lab. These organoids were genetically engineered to mimic the conditions seen in Alzheimer’s disease, including the tendency to overproduce amyloid beta.

What they found was striking.

When the researchers introduced the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2—the key used by the virus to enter human cells—amyloid beta levels spiked inside the retinal organoids. This suggested that viral exposure could directly provoke the kind of protein accumulation associated with neurodegeneration.

A Dangerous Doorway: NRP1 and Viral Entry

How does the virus get into these cells in the first place?

The scientists looked closely at two key proteins suspected of playing a role in viral entry: ACE2, the well-known gateway for SARS-CoV-2 into cells, and NRP1 (neuropilin-1), a lesser-known receptor that has emerged as a co-conspirator in helping the virus breach neural defenses.

In the retinal tissue of patients who had COVID-19, they discovered NRP1 proteins not only in neurons but also in glial cells—the brain’s support network. This confirmed that the eye, like the brain, offers entry points for the virus.

Then came the breakthrough: When the team exposed healthy human retinal samples to the virus’s spike protein, they again saw a rise in amyloid beta. But when they inhibited NRP1, the accumulation of amyloid beta stopped.

In short: Block NRP1, block the damage.

“This gives a specific molecular target for future investigation,” Hafler says. “NRP1 has already been explored as a possible cancer therapy, but this study opens a whole new direction—treating virus-induced cognitive disorders.”

Not Just Brain Fog: A New Threat to Memory

One of the pandemic’s most frustrating symptoms has been brain fog—a hazy, sluggish state of mind that affects attention, memory, and decision-making. For many people, it lasts weeks or even months after recovery. But now, it’s looking more and more like this fog could be the beginning of something more serious.

Hafler’s study revealed that even patients without dementia, but with a history of COVID-19, had higher amyloid beta levels in their retinal tissue than healthy individuals. In fact, the levels were comparable to those seen in Alzheimer’s patients.

While this doesn’t prove that COVID-19 causes Alzheimer’s, it adds weight to the idea that viral infections might increase long-term risk—especially for people already genetically vulnerable.

“It bolsters the amyloid beta antimicrobial hypothesis,” Hafler says. “It suggests that amyloid beta could be part of the brain’s innate immune response against viral infections.”

Hope on the Horizon: Toward a Treatment

If a virus like SARS-CoV-2 can induce amyloid plaque formation, the implications go far beyond COVID-19. Other viruses—possibly even herpes or influenza—might trigger similar processes.

But there’s good news: if the pathway can be mapped, it can potentially be interrupted. That’s where NRP1 inhibitors come in.

Currently used in preclinical trials as anti-tumor agents, NRP1 inhibitors may one day be repurposed to protect the brain from viral-induced damage. And by targeting the virus’s access point, rather than the virus itself, such treatments could work against a range of pathogens.

“Our ultimate goal is to prevent long-term neurological effects of COVID-19,” says Hafler, “and explore NRP1 inhibitors and other modulators of virus-host interactions as potential therapeutics for preventing viral-induced amyloid pathology and Alzheimer’s disease.”

The Beginning of the Story, Not the End

For now, the research continues. Hafler’s team is launching clinical studies at Yale School of Medicine to investigate whether people who’ve had COVID-19 are at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s—and whether early intervention can stop it.

One thing is clear: the pandemic is leaving more than just a medical and social legacy. It is also revealing how fragile, and how interconnected, our immune defenses and our minds truly are.

Through the eye, we’re learning more about the brain. And through a virus, we’re uncovering new truths about a disease that steals memory, identity, and time itself.

This may just be the beginning of a new frontier in neuroscience—where infection, immunity, and cognition meet.

Reference: Sean J. Miller et al, SARS-CoV-2 induces Alzheimer’s disease–related amyloid-β pathology in ex vivo human retinal explants and retinal organoids, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads5006